Democracy in Action: Students Step Up as Key Decision Makers

These high school students join their newly formed community council and get the chance to help govern their school.

Your content has been saved!

Go to My Saved Content.

Running Time: 7 min.

For the students and staff of Hudson High School, in Hudson, Massachusetts, civics isn't just a class. It's part and parcel to everyday life at this New England high school, which has become a laboratory of democracy, challenging widely held assumptions about how schools can and should operate.

Several years ago, when the district set out to build a new high school facility, Superintendent Sheldon Berman, longtime principal John Stapelfeld, and the entire Hudson High community embarked on a journey that would take them to uncharted waters.

Their mission: to plan and build a school whose design would encourage a sense of community among its occupants and to move into the new facility after having laid the groundwork for a bold new experiment in school governance in which students have a say in the big and little decisions that make up school life.

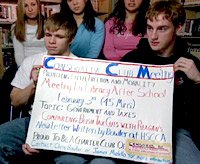

At the core of Hudson's grand experiment is the community council, a committee consisting of elected students and staff that is responsible for making many decisions at Hudson typically left to the school principal or a faculty committee to decide. Meeting once a month, the committee (led by a student, rather than a teacher) discusses and recommends policy on everything from dress codes to lunchtime fare to parking policies and more.

"Everyone on the council speaks with an equal voice," says Brian Daniels, a teacher at Hudson and executive to the Hudson High School Community Council. "It took a long time to get everyone ready for the change," he adds. Hudson students and staff discussed the new governance idea for two years before holding their first Community Council meeting.

One of the biggest challenges for students and staff was the shift of thinking -- and, in some ways, the shift in power -- that needed to occur in order for the Community Council to be effective.

"It really pushes me to look at whose opinion should be valued more," reflects Sean Tanney, a Hudson graduate and head of the Community Council last year. "When the teacher says something, you normally think of it as right, and if a student says something, you always look to the teacher to reconfirm that," said Tanney. "However, in Community Council, whoever says something, it's automatically valid, regardless of who said it."

The Community Council is governed by a three-page constitution, which lays out terms of service for representatives, election procedures, responsibilities, and areas of authority, which include "all matters at Hudson High School not controlled by school board policy, state policy, administrative regulations established by the Superintendent of Schools, and the collective bargaining agreement." The principal can veto council decisions, but the council can override the veto by a two-thirds majority vote, a move that triggers the creation of a Board of Conciliation, which includes the district superintendent, a Community Council member, and a third person with expertise in the area under question.

Although the Hudson Public Schools has received considerable praise for its initiative (the district is part of the First Amendment Schools project), it's also opened itself up to more scrutiny, perhaps, than the typical U.S. high school. Hudson's administration found itself in the middle of a controversy last year when students from the school's Conservative Club accused Principal Stapelfeld of violating their right to free speech when he removed a reference to a Web site he considered inappropriate (they featured videos of beheadings of hostages by Iraqi terrorists).

Boards of Conciliation and lawsuits over free speech violations may sound like more than most superintendents would bargain for. But to Berman, the debate and day-to-day practice at democracy brings the school and the district one step closer to fulfilling the true mission of public education.

"I always believed that the primary mission of public education is to develop effective citizens," says Berman. "Our efforts, both instructionally and in the very structure of the governance system we've developed, are designed to complicate students' thinking," and to help then learn to appreciate and listen to diverse opinions and perspectives.

"If we do those two things," says Berman, "they will become good citizens, and I think they'll also become better people."