At-Risk Students Make Multimedia

A team of college professors and K-12 teachers discovers how building video games can elevate student performance.

Your content has been saved!

Go to My Saved Content.

It's no surprise that Crenshaw High School served as the backdrop for the 1991 movie Boyz in the Hood, about an impoverished, crime-plagued South Central Los Angeles neighborhood.

For one thing, since 2003, it's been designated a High Priority/Program Improvement School by the Los Angeles Unified School District (LAUSD) because of low test scores -- only about 10 percent of roughly 2,000 kids are testing at proficient levels or above on federally mandated No Child Left Behind tests. Graduation rates hover around 50 percent, and about one-third of the teachers leave after three to five years of service.

But an emerging, national trend has the potential to change the picture for Crenshaw and schools like it. Increasingly, institutes of higher education are collaborating with K-12 teachers to help them use digital tools to get at-risk students excited about learning.

These well-endowed academic think tanks -- located at universities such as Indiana University, the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Ohio State University, and the University of Chicago -- are creating local projects they hope will close the gap between students' frequent use of multimedia tools and the barriers that prevent teachers from employing these tools in the classroom.

At the University of Southern California, with its 37-year tradition of creating joint projects for its graduate students and the local community, a number of educators within the College of Letters, Arts, and Sciences are seeking new ways to combine their cutting-edge research with real-world practice.

"We want our undergraduates to create projects, not just write papers," says Holly Willis, director of academic programs at USC's Institute for Multimedia Literacy (IML). "This is key to our mission of conducting research on the changing nature of literacy in the 21st century. It's crucial to our own goal that our undergraduates make teaching and learning happen at the same time; that they become peer mentors within the broader community."

A Rewarding Approach

You can draw a straight line from Willis's philosophy -- which was also cited in the New Media Consortium's 2009 Horizon Report as one of five key trends that will impact K-12 educators within the next five years -- and Crenshaw's January 2009 launch of a small pilot program called GameDesk. This pilot, which takes state-based standards for high school art and math and reimagines them through the multimedia platform of building video games from scratch, was conceived and created by USC professor Lucien Vattel, associate director for game research at the university's Viterbi School of Engineering. The pilot was implemented at Crenshaw by Scott Spector, the LAUSD's director of educational technology.

In one sense, GameDesk is like any other math or history class. In the program, two teachers and 40 students in grades 10-12 read specially created workbooks that lay out the basic principles of, say, fractions, percentages, algebraic equations, or World War II battles and strategy. Their teacher --Vattel or a USC undergraduate -- clarifies the material in classroom lectures.

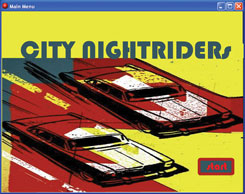

Students are tested, too, but as a warm-up leading to the goal of creating a video game. The classes also cover the elements of game theory, computer basics (such as opening files and storing images), and programming skills to move images on screen. Finally, the students apply their new knowledge of math or history to build one of four types of video games.

According to Vattel, creating a video game confers pride of authorship on students. It is qualitatively different from simply playing them but just as rewarding. Working individually and then in teams, "they always have sight of a tangible reward," says Vattel. In this teaching model, students understand their math lessons in context; their ability to make a character move right or left onscreen was directly tied to mastering x-y Cartesian coordinates.

"We've never forced difficult information on them," Vattel says. "They actively employed strategic thinking and problem solving that is engaging, interactive, creative, and rewarding."

"That's the key," says Spector. In Spector's experience, he says, the schools most in need of big changes are often the ones most willing to embrace cutting-edge ideas. "When you've got a majority of students reading three to five grade levels below where they should be, a population of kids who aren't motivated, for whom homework isn't important and grades don't matter, you've got to try a new way of doing things." And it works.

"When I went into one of those classrooms where the kids are normally loud and disruptive, I could hear a pin drop," Spector notes. "They were intensely focused."

A Winning Combination

Spector will soon have the data to prove his claim. This fall semester, he and his team have expanded the program. Two high schools -- Crenshaw and Polytechnic High School, in the San Fernando Valley -- will offer 90 students the chance to participate in a 20-week tech-art class. In the course, students will learn state-mandated math and art curriculum requirements by building video games.

Cathy Garcia, one of the two teachers who participated in Crenshaw's initial spring 2009 program, highlighted a few extraordinary classroom moments. "Although these students often have a difficult time engaging with mathematics, they threw themselves into the task of mastering the programming in the Game Maker software," she wrote in a year-end evaluation. "The normally rambunctious students were silent and engaged with their work -- enjoying themselves while working out problems on ratios, proportions, graphing, and conversions."

By March 2009, at the initial pilot program's halfway point, the Crenshaw students had completed their assigned game, so, working in teams, they chose new games to build. In April, the teams showed off their new games at the Information Technology Conference (Info-Tech), a convention where 90-plus schools presented technology-based projects.

Spector remembers a ninth-grade student with mild autism who stood up at the convention and presented his team's game. "He suffered from communication problems, but in this class, he became the team leader," Spector says.

University Support

Spector credits both the inspiration for the program and its successful evolution to the faculty and philosophy of nearby USC, as well as to Vattel. The game-making software was free, but Vattel and his undergrad students trained Crenshaw's teachers for a week during the summer, developed the course syllabus, helped create the workbook tutorials, and provided support when either a teacher or student got stuck.

For Spector, the seed of the project was planted when a colleague found an article about Vattel online. "When I saw that you could get an undergraduate degree at USC in gaming, I was knocked out," he said. "After all, these kids are playing video games six, eight hours a day. Could we use video games as a project-based solution so my students can understand and learn the same content other kids are able to glean from a textbook or a lecture?"

At USC and other institutes of high education, the need to reach out to K-12 educators and address how literacy is no longer limited to reading, writing, and arithmetic is an increasingly urgent priority. For a person to be literate in the 21st century, he or she must master symbol systems -- the visual, electronic, and digital forms of expression so overwhelmingly present in today's culture.

"The issue of digital literacy lies in knowing what to do once you're connected," says Fran&cced;ois Bar, associate professor of communication at USC. When you consider the fact that, according to a Kaiser Family Foundation study, kids in the United States ages 8-18 spend an average of six hours or more using media each day, it becomes that much more urgent for educators to become fluent in digital literacy. And USC's Institute for Multimedia Literacy seeks to address the issue with a variety of programs.

In Bar's formulation, literacy -- whether it's achieved with pen and paper or with a video camera -- is the ability to tell and share stories; it is about authorship. "What happens to a story after it's been told?" he asks. "The audience members must understand the story, transform it, and retell it in their own way. Stories told in digital media have the ability to be copied and remixed and to cross geographic boundaries through electronic outlets."

According to Bar, digital technologies take us back to humanity's storytelling roots. What was true of the ancient Greeks who maintained a vast oral tradition of epic poetry through repetition and embellishment, or of medieval troubadours who spread songs across continents, with each new singer making alterations, is also true of content created in digital media.

"In our program," says Vattel, "we're no longer telling the kids to put their technology away. We want to embrace it. This is a major way kids understand their lives."

Game making, he adds, is not the same as game playing. "This is a nonlinear authoring process that emphasizes problem solving and critical thinking. It challenges students to sit down and create a complex system."

Universities Can Help

USC senior lecturers Stephanie Bower and John Murray have tapped into the IML's expertise to create a class for their undergraduates that builds digital-literacy skills. The college students partner with at-risk high school students at several continuation schools and a juvenile-detention facility in Los Angeles.

With a $5,000 grant from USC, Bower and Murray purchased a Mac laptop, hard drives, Flip cameras, and video-editing software the kids used in making documentaries relevant to their communities. As a writing teacher, Bower believes that visual forms complement traditional writing assignments.

"It's not one form versus another," she explains. "It's about recognizing how powerful images have become in our culture. It's about tapping into the power of storytelling and learning how to construct your own narrative. With YouTube and the Internet, we now have a powerful distribution method that allows stories to reach a much broader audience than they would if they simply appeared in the school newspaper."

Vattel and Spector want to expand the GameDesk program to all 34 LAUSD High Priority/Program Improvement Schools. For that, they'll need corporate and other sponsors.

"Having more financial resources will enable us one day to take this program to a national audience," says Vattel. "But my general rule is, the one thing that matters most is the individual teacher. You do need support from the administration. You do need technical tools. But if you don't have a teacher who believes in this zany idea -- that you can embed game-making technology into the curriculum no matter what the subject -- then it won't work."

Vattel encourages public school teachers to seek resources from their local university. "So much of the experimenting with new pieces of software and technology is happening on the collegiate level," he says. "We have the knowledge and often the budget to help local schools. We get to push the boundaries of these amazing interactive toys. It's our obligation to bring this knowledge to our local schools."

Vattel mentions a 55-year-old biology teacher who attended the winter tutorial. She had never played a video game in her life. By the end of the week, she had built three game levels. "It just takes a little time," he says. "The next thing you know, they've got a game."