Full House: As Las Vegas Grows, So Does the Need to Accommodate Its Students

The Las Vegas building boom has stretched the creativity and resources of the fastest-growing school district in the nation.

Your content has been saved!

Go to My Saved Content.

Running Time: 10 min.

Editor's Note: Carlos Garcia moved on from the Clark County School District in 2005. He now serves as superintendent of the San Francisco Unified School District. Carol Lark, principal of C.P. Squires Elementary School when this article was written, has also left the Clark County School District and is now superintendent of a school district in northern Nevada.

New York may be the city that never sleeps, but Las Vegas is the city that never stops building. Ever.

This once sleepy community, founded by Mormon missionaries in 1855 and jump-started by gambling eighty-five years later, now gobbles up real estate faster than a conventioneer chowing down at a midnight buffet. Every day of the week, two acres of Las Vegas-area land are developed for commercial or residential use in a frenetic drive to accommodate the 50,000 newcomers who pour in each year. These transplants come from all over the world and all walks of life, looking for a fresh start and a chance to cash in on their piece of the American dream: an affordable house, a steady job, and a good school for their kids.

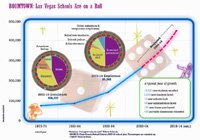

The booming economy is good news for Las Vegas and for Nevada, but it creates big challenges for the area's schools. The Clark County School District, which stretches across 8,000 square miles in southern Nevada, is like no other in the nation. As the fastest-growing school district in the country, it faces the annual challenge of building twelve schools, hiring 2,000 teachers, and accommodating 12,000 new students.

This once small and fairly homogenous district is now the sixth largest in the United States (New York City's, Chicago's, and Los Angeles's top the list, followed by those of Florida's Dade and Broward counties), with all the diversity you would expect from a system of 270,000 students.

More Community Collaboration

<?php print l('Video: Betting on Change', 'betting-change'); ???????>

: Las Vegas's booming economy challenges the area's schools. <?php print l('Watch how', 'betting-change'); ???????>

Learning Around the Clock

<?php print l('Audio: An-Me Chung', 'me-chung'); ???????>

: "After-school programs can inspire the education community." <?php print l('Listen', 'me-chung'); ???????>

<?php print l('Go to Complete Coverage', 'new-day-for-learning'); ???????>

Over the last fifteen years, the Clark County School District has evolved from a predominantly white, middle-class school system to a mixed-income one in which minority students are in the majority. Twenty percent of all new students speak a language other than English, and twice that many are eligible for free or reduced-price lunches. The increasingly diverse student body poses additional challenges for a district already stretched to its limits -- from eliminating the achievement gap among students of different races and income levels to keeping highly qualified teachers in its neediest schools.

"Clark County schools have more challenges than Heinz has pickles," says longtime Las Vegas resident Ann Lynch, a cofounder of the Clark County Public Education Foundation and a former National PTA president. The biggest challenge of all: to stay one step ahead of the growth while providing current students with the support and services they need to succeed in school -- and in life.

Six Years, Fifty-Seven Schools

Buying land and building and furnishing a dozen new schools per year is no small undertaking. It requires a 300-person facilities department, including teams of statisticians and demographers, real estate specialists, architects, construction managers and workers, and more. It also requires cash -- lots and lots of cash.

In 1998, voters and the state legislature passed an unprecedented $3.5 billion capital-improvement program to fund a ten-year plan to build eighty-eight new schools and to renovate or replace aging facilities. Six years later, the district has opened fifty-four new schools and built three replacements.

"We don't see any slow up in the growth for as far out as we can look," says Dale Scheideman, director of the district's New School and Facility Planning Department, adding that the district's multibillion-dollar, multiyear building plan depends on accurate forecasts of student population growth. District demographers, who have become experts at projecting future enrollment, can predict within half of a percentage point what the student count will be two to three years out. But knowing how many students will be enrolled in the district each year and knowing what schools they'll be enrolled in are two entirely different matters.

"We can tell you exactly how many kids are going to enroll in September," says Scheideman. "We're just not really sure where they're going to show up."

This condition is a by-product of the rampant transience that is life in Las Vegas. Scheideman estimates that 35 percent of all students change addresses every year, driven, in large part, by the changing economics of the area: Families move up and down the income ladder as jobs come and go. The lucky ones move from cramped apartments in the inner city to shiny new ranch homes in the suburbs. The less fortunate slip in and out of the area's many residential hotels, always waiting for the big break that will turn their lives around.

Adding to the constant flux is the group of students who are required to switch schools each year to balance the population and ease overcrowding. The constant movement of children and families throughout the district stretches its facilities department, as portable classrooms are moved from school to school to accommodate unexpected overflows of students. It also makes the already challenging task of educating the area's youth even more difficult: Communities aren't formed easily, nor is curriculum mastered easily, when students and staff move frequently.

The Big Leagues

The Clark County School District began its extended growth spurt in the late 1980s, adding as many as 14,000 new students a year, as construction and service jobs lured hundreds of thousands of new families to the area.

Despite Las Vegas's steady growth and its spotlight of attention, its school district plugged along mostly unnoticed, never really capturing national attention or taking its place among the largest, most influential systems in the country. Then along came Carlos Garcia, a Latino educator from California's Central Valley, who was named superintendent in 2000. Although his predecessor had been content to let the district fly below the national radar screen, Garcia was determined to make it into a player on a bigger stage.

"As a district, you can't be isolationist," says Garcia. "People need to know you exist, or you lose out on money and opportunities." That broader focus has paid off: The year Garcia became superintendent, the district received just $40 million in federal funds. Today, such budgetary contributions exceed $120 million.

Garcia possesses a winning combination of opened-eyed realism about the magnitude of the challenges before him, and unabashed optimism that the Clark County School District has the drive and determination to overcome its hurdles. In one breath, he acknowledges the district's high dropout rate (7.5 percent, one of the country's highest) and the difficulty his administration faces meeting the needs of the system's growing population of Spanish-speaking students and families. In the next, he waxes poetic about all that's right in public education.

"Sometimes our critics will say, 'American public schools aren't working,'" Garcia says. "I completely disagree. Public schools are working better than ever.

"Our cup is not empty," he adds in one of his trademark sound bites. "It's overflowing with good things." Garcia's a politically savvy administrator, but he's also an educator of some thirty years' experience whose first priority, say friends and colleagues, is serving the 270,000 students in his charge.

"Carlos has a way of always asking, 'Is this good for kids?'" says Ray Chavez, an administrator in the Tucson (Arizona) Unified School District who spent six months working alongside Garcia as part of an internship through the Harvard University Urban Superintendents Program. "Carlos knows all the statistics and the numbers, but that's not what ultimately drives him," he adds. There's widespread admiration for the work Garcia and his approximately 1,000 administrators have done thus far. They've strived to make the massive district smaller and more personal by creating geographic regions within it, each with its own superintendent and administration. They've launched algebra and literacy initiatives to boost achievement and provide more opportunities for students to be successful, and they are moving schools and administrators toward a decision-making model that's based on research and data rather than individual opinions or past practices.

But even with these positive steps, admirers acknowledge that success -- in the form of high achievement for all students -- is not guaranteed.

Clark County teachers help kids become confident, capable readers with a wide range of learning tools.

Credit: Clark County School DistrictChange on a Grander Scale

Like any large district, Clark County's is a study in contrasts. Its schools serve students from families of incredible poverty, who live in residential hotels or on the street, as well as the children of Las Vegas's version of landed gentry. Among its nearly 300 schools is a National Blue Ribbon School (the Advanced Technologies Academy), whose integration of academics and technology garnered the attention of First Lady Laura Bush.

Conversely, sixteen Clark County schools were on a needs-improvement list during the 2003-04 school year for not having met their annual yearly progress as specified in the federal No Child Left Behind Act. The district is home to cutting-edge projects, such as its new Virtual High School (in which students take all their classes online), which will "open" with 500 students this fall, and yet it still struggles to prepare all teachers to fully integrate technology into their daily classroom instruction.

Whether the issue is raising student achievement or better preparing teachers, the primary challenge for Clark County's school district is one of scale. Throughout the district, individual schools or regions have adopted effective programs to address a wide range of problems and concerns, but implementing those changes throughout the system is another matter.

"In a district that's always growing and always changing, it's a challenge to make any [program] systemic," acknowledges Karlene McCormick-Lee, the district's assistant superintendent of research, accountability, and innovation. But such change is exactly what the district needs and what Garcia demands in response to what he describes as "the good, the bad, and the ugly" of Clark County schools. Two initiatives that top the long list of academic priorities focus on algebra and literacy -- curriculum areas in which achievement has a dramatic affect on students' overall academic success.

In 1999, only 10 percent of all eighth graders in the district were enrolled in an algebra course. Although some students took the course in high school, a significant percentage never enrolled at all, lowering their chances of passing the state's high school exit exam or going on to college. But the district's algebra initiative, begun in 2001, turned those numbers around. By fall 2003, 70 percent of all eighth graders were enrolled in algebra; of those students, 75 percent passed the class and were ready to go on to higher-level math. By the 2006-07 school year, the district hopes to bring enrollment numbers for eighth-grade algebra up to 100 percent.

Christy Falba, the district's director of K-12 math, science, and instructional technology, credits its professional development, investment in new-technology tools, and revamping of the K-8 math curriculum for its steady progress. Working with the University of Nevada, Las Vegas, Nevada's Regional Professional Development Program, and the Southern Nevada Mathematics Council, district math teachers are participating in a host of professional-development courses designed to improve their teaching of algebra and find new ways to serve students of diverse needs and abilities. For some students, that means taking a traditional one-year course over a two-year span. For others, new-technology tools, such as I Can Learn Algebra , by I Can Learn Education Systems, and Algebra Tutor, by Carnegie Learning, are employed to help them master the skills.

The district's second large-scale initiative, to have every child reading at grade level by the end of third grade, hasn't met its ambitious aim. But, as with the system's algebra program, new technologies and alternative teaching techniques, like the use of LeapFrog learning products and other software tools in early grades, and extended professional-development programs that emphasize strategies for working with struggling readers, have been brought to bear on the problem. The administration has also enlisted the aid of the community through Clark County Reads, a partnership between the district, the Clark County Public Education Foundation, and the Las Vegas Chamber of Commerce that upgrades libraries, provides books for needy students, enlists community volunteers to work with struggling readers, and more.

Although throughout the district, third-grade reading-proficiency scores still hover near 50 percent, some schools note big improvements. For example, C. P. Squires Elementary School is considered a model for what the district is trying to achieve. The school, with roughly 97 percent Spanish speakers, has instituted a variety of programs and services to meet the literacy challenge: Educators here match community members and older students with struggling readers, have piloted the use of LeapFrog and other new-technology tools to support early literacy, and have developed after-school and evening programs for students and parents.

One of the school's most successful efforts is its full-day kindergarten program, which former principal Carol Lark (she was recently promoted to assistant area superintendent) credits with ensuring that students are ready for first grade. The program extends the day for kindergarten students by three hours, providing students and staff, respectively, with additional time to develop language-acquisition skills and better prepare students to move on.

"When they come into kindergarten, 90 percent of our little ones don't speak a word of English," says Lark. Full-day kindergarten (paid for with federal Title 1 money) "allows us to maximize the time we have," she adds. "It gives us six hours each day to teach our children to read."

The full-day kindergarten program will become more widespread this fall, when fifty-four of the poorest schools will switch to the longer school day. (In twelve of the district's more affluent schools, the full-day program will be available for a fee.) It's part of a districtwide effort to identify what's working, says Garcia, and then implement successful programs on a larger scale. "We don't have enough money to do everything," Garcia adds, "but we do have enough money to focus it so the best programs [are in place] throughout the district."

The Missing Piece

Although district staff have devoted considerable time and attention to evaluating the effectiveness of school-based programs and developing greater consistency from one campus to the next, observers say one key area has yet to be fully added to the reform mix: parent support and involvement.

Because the Clark County School District has 270,000 students and 30,500 employees, it's daunting and difficult to navigate. In part to bring it closer to the community, the district was restructured in 2000, creating five geographic regions within it. But because enrollment in each region hovers around 60,000 (making each about the size of one of the 30 largest districts in the country), the system still often feels remote and complicated.

Debbi Stutz, the mother of four children who have gone through the Clark County school system, speaks slowly and selects her words carefully as she shares a parent's view on the district. "I greatly appreciate what the district was trying to achieve with the regions," she says, "but from a parent's perspective, it's still hard to find the person you need to talk to and then to be heard. I've been involved for twenty years, and even with that much experience and recognition, [the system] can still be hard to navigate."

Navigation becomes even more challenging for the district's growing population of Latino parents, who often don't know the system, the city, or the language. The district's Web site is chock-full of information, but the vast majority of it is provided only in English. In addition, says Stutz, calling the district offices can often result in being transferred from one office to the next in search of someone who can help.

In an effort to reach out to the district's Latino parents, the Nevada PTA recently sponsored a workshop where Spanish-speaking parents were introduced to the ins and outs of the Clark County school system and received tips and advice on how best to advocate for their children. The program, which will later match new parents with mentors, is modeled after a National PTA program that has been piloted in Texas, Florida, and California.

This forum was a good first step, says Stutz, but, she's quick to add, it's not enough. Although individual schools and regions actively seek community and parent involvement, she believes the district itself must take more of a leadership role if parents are really to become partners in their children's education.

Garcia acknowledges that the regions haven't been as successful as he'd like in making the big district seem small. "In the long run, they'll help make the district more user friendly, but we still have a way to go with that," Garcia says.

Community volunteers mentor students and provide them with academic and emotional support.

Credit: Clark County School DistrictThe Road Ahead: Driven by Data

Involving parents, developing strong readers, keeping kids in school through graduation -- the list of challenges facing the Clark County School District are many and growing. The district's statisticians have projected steady growth for as long as they can accurately predict, and there's little chance that teachers, parents, and administrators will be able to catch their breath any time soon.

One tool the administration has high hopes for is a customized database that will be used to track each of the district's students, as well as groups of students (by gender, socioeconomic status, ethnicity, and so on), enabling educators and parents to understand and respond to academic needs.

The district is "just beginning the conversation about using past performance and student data to make decisions," says McCormick-Lee, whose department is responsible for implementing the new system. It takes years, she adds, to change the culture and the practices of a school system so that educators are open and responsive to making changes based on what the data tells them.

Although data is increasingly used for punitive purposes throughout the country, Garcia doesn't believe you need to, as he puts it, "beat people up" in order to affect real change. Instead, he believes data can empower everyone -- parents, classroom teachers, even district administrators -- to identify strengths and weaknesses and to implement curriculum and programs that will serve students.

The Clark County School District's data doesn't always tell a glowing story, as Garcia is quick to acknowledge. Per-pupil funding is $1,500 below the national average, the district's average class size is the fifth largest in the country, and even its $3.5 billion building budget isn't likely to be enough to fund all the projected growth.

Still, Garcia remains remarkably optimistic about the district and, by extension, about public education throughout the country. "The issues here represent the future of education, and that's pretty exciting," he says. "If we can make things work here, in spite of the lack of resources, then we can make them work anywhere. That's a great challenge."

Roberta Furger is a contributing writer for Edutopia.

Teachers Wanted; Signing Bonus Offered

Latonya Freeman was reading the paper one weekend morning at her Laguna Hills, California, home when she saw an ad for the Clark County School District, whose representatives were in town interviewing teachers. On a whim, she picked up the phone and scheduled an appointment. Six months later, she's heading to North Las Vegas to begin teaching at Jim Bridger Middle School, joining the ranks of roughly 2,000 new teachers who are added to the district's payroll each fall.

"The opportunities in Clark County seem to be more plentiful than in California," says the English teacher.

Freeman doesn't know a soul in Las Vegas, so she's a little anxious about the move. She's heartened, though, by the phone calls and emails she's received, welcoming her to the district and assisting her with everything from locating an apartment to hooking her up with a mentor teacher once she arrives.

Observers say Clark County's school district, which relies on the Internet to screen applications and streamline the hiring process, has the hiring of teachers down to a science. With a couple mouse clicks, Lina Gutierrez, the district's executive director of human resources, can identify how many people have applied for teaching positions, and can determine the up-to-the-minute status of any application.

"We do everything we can electronically," says Gutierrez. "Otherwise, we'd never be able to do it."

Like Freeman, most of the district's 2,000 new teachers come from outside Nevada, but Gutierrez and her staff are also implementing plans to attract local residents to the teaching profession, including programs for parents and district support staff. Once a new teacher is hired, the district's teacher-induction program kicks into gear with welcome calls, email messages, and a vast array of orientation services and programs ranging from help navigating the new community to yearlong professional-development and support programs for new teachers.

For the Clark County School District, a high-tech, high-touch employment process helps meet the need for a constant influx of teaching staff.