Reshaping Learning from the Ground Up

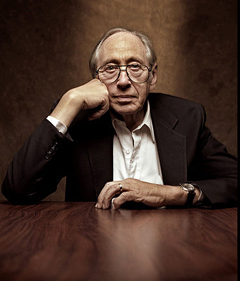

Alvin Toffler tells us what’s wrong — and right — with public education.

Your content has been saved!

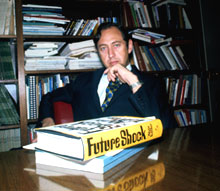

Go to My Saved Content.Forty years after he and his wife, Heidi, set the world alight with Future Shock, Alvin Toffler remains a tough assessor of our nation's social and technological prospects. Though he's best known for his work discussing the myriad ramifications of the digital revolution, he also loves to speak about the education system that is shaping the hearts and minds of America's future. We met with him near his office in Los Angeles, where the celebrated septuagenarian remains a clear and radical thinker.

You've been writing about our educational system for decades. What's the most pressing need in public education right now?

Alvin Toffler: Shut down the public education system.

That's pretty radical.

I'm roughly quoting Microsoft chairman Bill Gates, who said, "We don't need to reform the system; we need to replace the system."

Why not just readjust what we have in place now? Do we really need to start from the ground up?

We should be thinking from the ground up. That's different from changing everything. However, we first have to understand how we got the education system that we now have. Teachers are wonderful, and there are hundreds of thousands of them who are creative and terrific, but they are operating in a system that is completely out of time. It is a system designed to produce industrial workers.

Let's look back at the history of public education in the United States. You have to go back a little over a century. For many years, there was a debate about whether we should even have public education. Some parents wanted kids to go to school and get an education; others said, "We can't afford that. We need them to work. They have to work in the field, because otherwise we starve." There was a big debate.

Late in the 1800s, during the Industrial Revolution, business leaders began complaining about all these rural kids who were pouring into the cities and going to work in our factories. Business leaders said that these kids were no good, and that what they needed was an educational system that would produce "industrial discipline."

What is industrial discipline?

Well, first of all, you've got to show up on time. Out in the fields, on the farms, if you go out with your family to pick a crop, and you come ten minutes late, your uncle covers for you and it's no big deal. But if you're on an assembly line and you're late, you mess up the work of 10,000 people down the line. Very expensive. So punctuality suddenly becomes important.

You don't want to be tardy.

Yes. In school, bells ring and you mustn't be tardy. And you march from class to class when the bells ring again. And many people take a yellow bus to school. What is the yellow bus? A preparation for commuting. And you do rote and repetitive work as you would do on an assembly line.

How does that system fit into a world where assembly lines have gone away?

It doesn't. The public school system is designed to produce a workforce for an economy that will not be there. And therefore, with all the best intentions in the world, we're stealing the kids' future.

Do I have all the answers for how to replace it? No. But it seems to me that before we can get serious about creating an appropriate education system for the world that's coming and that these kids will have to operate within, we have to ask some really fundamental questions.

And some of these questions are scary. For example: Should education be compulsory? And, if so, for who? Why does everybody have to start at age five? Maybe some kids should start at age eight and work fast. Or vice versa. Why is everything massified in the system, rather than individualized in the system? New technologies make possible customization in a way that the old system -- everybody reading the same textbook at the same time -- did not offer.

You're talking about customizing the educational experience.

Exactly. Any form of diversity that we can introduce into the schools is a plus. Today, we have a big controversy about all the charter schools that are springing up. The school system people hate them because they're taking money from them. I say we should radically multiply charter schools, because they begin to provide a degree of diversity in the system that has not been present. Diversify the system.

In our book Revolutionary Wealth, we play a game. We say, imagine that you're a policeman, and you've got a radar gun, and you're measuring the speed of cars going by. Each car represents an American institution. The first one car is going by at 100 miles per hour. It's called business. Businesses have to change at 100 miles per hour because if they don't, they die. Competition just puts them out of the game. So they're traveling very, very fast.

Then comes another car. And it's going 10 miles per hour. That's the public education system. Schools are supposed to be preparing kids for the business world of tomorrow, to take jobs, to make our economy functional. The schools are changing, if anything, at 10 miles per hour. So, how do you match an economy that requires 100 miles per hour with an institution like public education? A system that changes, if at all, at 10 miles per hour?

It's a tough juxtaposition. So, what to do? Suppose you were made head of the U.S. Department of Education. What would be the first items on your agenda?

The first thing I'd say: "I want to hear something I haven't heard before." I just hear the same ideas over and over and over again. I meet teachers who are good and well intentioned and smart, but they can't try new things, because there are too many rules. They tell me that "the bureaucratic rules make it impossible for me to do what you're suggesting." So, how do we bust up that? It is easy to develop the world's best technologies compared with how hard it is to bust up a big bureaucracy like the public education system with the enormous numbers of jobs dependent on it and industries that feed it.

Here's a complaint you often hear: We spend a lot of money on education, so why isn't all that money having a better result?

It's because we're doing the same thing over and over again. We're holding 40 or 50 million kids prisoner for x hours a week. And the teacher is given a set of rules as to what you're going to say to the students, how you're going to treat them, what you want the output to be, and let no child be left behind. But there's a very narrow set of outcomes. I think you have to open the system to new ideas.

When I was a student, I went through all the same rote repetitive stuff that kids go through today. And I did lousy in any number of things. The only thing I ever did any good in was English. It's what I love. You need to find out what each student loves. If you want kids to really learn, they've got to love something. For example, kids may love sports. If I were putting together a school, I might create a course, or a group of courses, on sports. But that would include the business of sports, the culture of sports, the history of sports -- and once you get into the history of sports, you then get into history more broadly.

Integrate the curricula.

Yeah -- the culture, the technology, all these things.

Like real life.

Like real life, yes! And, like in real life, there is an enormous, enormous bank of knowledge in the community that we can tap into. So, why shouldn't a kid who's interested in mechanical things or engines or technology meet people from the community who do that kind of stuff, and who are excited about what they are doing and where it's going? But at the rate of change, the actual skills that we teach, or that they learn by themselves, about how to use this gizmo or that gizmo, that's going to be obsolete -- who knows? -- in five years or in five minutes.

So, that's another thing: Much of what we're transmitting is doomed to obsolescence at a far more rapid rate than ever before. And that knowledge becomes what we call obsoledge: obsolete knowledge. We have this enormous bank of obsolete knowledge in our heads, in our books, and in our culture. When change was slower, obsoledge didn't pile up as quickly. Now, because everything is in rapid change, the amount of obsolete knowledge that we have -- and that we teach -- is greater and greater and greater. We're drowning in obsolete information. We make big decisions -- personal decisions -- based on it, and public and political decisions based on it.

Is the idea of a textbook in the classroom obsolete?

I'm a wordsmith. I write books. I love books. So I don't want to be an accomplice to their death. But clearly, they're not enough. The textbooks are the same for every child; every child gets the same textbook. Why should that be? Why shouldn't some kids get a textbook -- and you can do this online a lot more easily than you can in print -- why shouldn't a kid who's interested in one particular thing, whether it's painting or drama, or this or that, get a different version of the textbook than the kid sitting in the next seat, who is interested in engineering?

Let's have a little exercise. Walk me through this school you'd create. What do the classrooms look like? What are the class sizes? What are the hours?

It's open 24 hours a day. Different kids arrive at different times. They don't all come at the same time, like an army. They don't just ring the bells at the same time. They're different kids. They have different potentials. Now, in practice, we're not going to be able to get down to the micro level with all of this, I grant you, but in fact, I would be running a twenty-four-hour school, I would have non-teachers working with teachers in that school, I would have the kids coming and going at different times that make sense for them.

The schools of today are essentially custodial: They're taking care of kids in work hours that are essentially nine to five -- when the whole society was assumed to work. Clearly, that's changing in our society. So should the timing. We're individualizing time; we're personalizing time. We're not having everyone arrive at the same time, leave at the same time. Why should kids arrive at the same time and leave at the same time?

And when do kids begin their formalized education?

Maybe some start at two or three, and some start at seven or eight -- I don't know. Every kid is different.

What else?

I think that schools have to be completely integrated into the community, to take advantage of the skills in the community. So, there ought to be business offices in the school, from various kinds of business in the community.

The name of your publication is Edutopia, and utopia is three-quarters of that title. I'm giving a utopian picture, perhaps. I don't know how to solve all those problems and how to make that happen. But what it all boils down to is, get the current system out of your head.

How does the role of the teacher change?

I think (and this is not going to sit very well with the union) that maybe teaching shouldn't be a lifetime career. Maybe it's important for teachers to quit for three or four years and go do something else and come back. They'll come back with better ideas. They'll come back with ideas about how the outside world works, in ways that would not have been available to them if they were in the classroom the whole time.

So, let's sit down as a culture, as a society, and say, "Teachers, parents, people outside, how do we completely rethink this? We're going to create a new system from ground zero, and what new ideas have you got?" And collect those new ideas. That would be a very healthy thing for the country to do.

You're advocating for fundamental radical changes. Are you an optimist when it comes to public education?

I just feel it's inevitable that there will have to be change. The only question is whether we're going to do it starting now, or whether we're going to wait for catastrophe.

Alvin Toffler's School of Tomorrow

These are the fundamentals of the futurist's vision for education in the 21st century:

- Open 24 hours a day

- Customized educational experience

- Kids arrive at different times

- Students begin their formalized schooling at different ages

- Curriculum is integrated across disciplines

- Nonteachers work with teachers

- Teachers alternate working in schools and in business world

- Local businesses have offices in the schools

- Increased number of charter schools

Books

Alvin Toffler's books examine the big issues our society faces as we forge into the future:

- Future Shock (1970)

- The Eco-Spasm Report (1975)

- The Third Wave (1980)

- Previews & Premises (1983)

- Powershift: Knowledge, Wealth, and Violence at the Edge of the 21st Century (1990)

- War and Anti-War (1995)

- Revolutionary Wealth (2006)