A Louisiana School Leader Answers the Call of Duty

After Hurricane Katrina, New Orleans principal Rene Lewis-Carter went above and beyond to reinvent her elementary school.

On the morning of December 15, 2005, little more than three months after Hurricane Katrina ravaged New Orleans, Rene Lewis-Carter welcomed students to the brand-new Martin Behrman Charter Academy of Creative Arts & Sciences. The school was among the first in the city to open after the storm. "We had no idea who would walk in the door," she says.

Lewis-Carter remembers looking out over a sea of children dressed in uniforms of the various neighborhood schools they had attended pre-Katrina. "All these little pockets of New Orleans and other towns were represented," she recalls with emotion. "I don't know how people evacuated with their school uniforms, but many of them did."

Well over half of the children at Behrman that morning were still homeless, living in shelters or trailers, or they had piled in with relatives or neighbors. Many hadn't been inside a classroom in six months.

The most important job, Lewis-Carter decided, was to make them all feel safe. "For weeks, we listened to their stories," she says. The children recounted horrific tales of floating from housing developments on mattresses and of enduring the misery at Houston's Astrodome.

Four years later, this emphasis on nurturing has evolved into a school credo Lewis-Carter calls "the Behrman Way." Simply stated, it means putting the children first in all decisions. This commitment often involves going above and beyond the basic requirements -- sometimes far above and beyond -- because, as Lewis-Carter says, "our children need so much more."

Some 628 children, nearly all black, nearly all poor, attended grades preK-8 at Behrman this year. The "much more" the school offers includes everything from immunizations (there's a medical clinic across the street from the school) to haircuts (one of the third-grade paraprofessionals is also a barber) to Easter dresses, Lewis-Carter says.

If a child doesn't have the clothes she needs for her Easter pictures, it's the teacher's job to recognize that her family may be struggling and to tap the petty cash fund and buy her a dress. The idea, she explains, is to "take the burden off of the children so they will be free to learn."

The strategy seems to be working. During Lewis-Carter's four years as principal, she has led these children -- disadvantaged by every conventional measure and further handicapped by the hardships of Katrina -- to a stunning performance record on state-mandated standardized tests, one that compares favorably with the city's selective-admissions schools.

Connecting with Kids

On a recent morning, I join Lewis-Carter in the basement of Behrman as she greets children for the day. A little boy stands next to her, waiting to be noticed. Javoni is upset, and before he heads off to another day of first grade, he wants to tell Lewis-Carter about it.

"What's the matter, baby?"

"My mama didn't let me finish my ice cream."

She leans down to give him a hug.

"That's your biggest problem? Your mama didn't let you finish your ice cream?"

Later, she tells me she will stop by his classroom and give him something to cheer him up. It could be anything -- a pencil, maybe. "He wants to have a conversation with me every morning," she says, smiling. "This morning, it was ice cream."

We walk upstairs to her office to chat. Despite the room's 18-foot ceilings, the principal's office is an unintimidating space, strewn with piles of papers and a Mickey Mouse tote bag and watched over by an oak grandfather clock. The building itself is handsome but derelict, a Spanish Revival-like pile that first opened its doors in 1931. It's covered in peach stucco and terra-cotta roof tiles that leaked even before the storm. Inside are signs warning of termite damage around the storytelling area at the back of the library.

Amid these rundown surroundings, Lewis-Carter is a dazzling presence. With her sophisticated ensemble and her red-framed glasses, she does not much resemble school principals as they are customarily represented in children's picture books. She has on a necklace that proclaims her love for her hometown, the silver letters spelling the abbreviation "NOLA."

Today, she has come to work wearing a trim, melon-colored spring coat and blue patent leather high heels with a strap across the vamp. She later replaces these with yellow moccasins. They are more practical for the continual "popping in" that makes up this principal's day, which includes marching through the long line of classes and down to the first floor to prekindergarten and the severe/profound class, where children with severe disabilities come every day.

"These children truly depend on us, to tube feed them, to suction where it's necessary, to provide medical care," she says of this class. "I go there to get grounded."

In Her Blood

Rene Lewis-Carter is a third-generation resident of Algiers, located on a bend in the river across from the more familiar tourist precincts of the French Quarter. She lives a few blocks from school in the charming and gentrified neighborhood of Algiers Point.

Like many New Orleans natives, she's passionate about historic preservation and proud of her more-than-160-year-old mauve Edwardian shotgun double house, built in an architectural style that is highly sought after in the Big Easy. It is, she says, very much like the one her grandmother owned.

The daughter of two educators, Lewis-Carter did not grow up wanting to be a teacher. "School was stressful to me because all I ever did was school," she admits. "And my parents were always out educating someone else's children." To make ends meet, both parents worked nights (her mother at a local college, her father doing odd jobs) in addition to their day jobs in schools.

Lewis-Carter, meanwhile, went to summer school every year, graduating from high school at 15 and Our Lady of Holy Cross College at 19. She imagined a career in business, but by the time she was 20, she found herself back at her old high school teaching students only two years younger than herself -- and she hated it. So she flew away, becoming a flight attendant for Southwest Airlines.

After two years working in hospitality, she returned to New Orleans and eventually to teaching, pulled to the same calling as her parents, who were a great influence on her life. This time, working in education felt right, even predestined. Some of her colleagues in both the Jefferson and Orleans Parish school systems were people who had known her parents before she was even born.

"To this day, I run into people who were their students and who remember them with respect and affection," she says. "Doing the work I do, I feel that my parents are still with me and that they validate my purpose."

In 2001, she accepted a position as an assistant principal at Carter G. Woodson Middle School. She and her mentor, then principal Mary Laurie, were given a tall order: Turn around a middle school in which a 13-year-old and a 15-year-old had shot each other in a schoolyard incident.

The first thing they did, Lewis-Carter remembers, was paint the graffiti-covered walls themselves, with the help of the faculty and staff: "We believed the children deserved that." Several years later, she landed her first job as a principal, at Harriet Ross Tubman Elementary School, which is now a charter school.

She was in the middle of preparing for the 2005-06 school year when Hurricane Katrina hit in late August.

The Aftermath

During the storm, Lewis-Carter evacuated to Houston with her husband, James Carter, a lawyer, and their then two-year-old son, Bryce. The couple volunteered at the Houston Astrodome, which, like New Orleans's Superdome, had been converted into a temporary shelter. They learned after several days that their own house was little damaged -- Algiers is on high ground -- and they devoted themselves to helping less fortunate exiles from their beloved, but now broken, city.

Lewis-Carter spent two months in Houston in a lovely apartment, feeling guilty about her good fortune and writing reference letters for New Orleans teachers seeking to relocate to Texas. All the while, she never doubted she and James would be coming home. "There is no spirit in the world like the spirit you will find in New Orleans," she explains. James decided to run for office and, after they returned in May 2006, he won a seat on the New Orleans City Council.

Lewis-Carter, however, was out of a job. Like virtually every public school principal and teacher in New Orleans following Katrina, she was fired at about the same time the state legislature voted to take over most of the city's public schools. The hurricane had devastated the school system, which was long ranked among the worst in the country, and it forced the schools to close, clearing the way for reform.

The shape this change would take became apparent in late fall, when the federal government announced the availability of nearly $21 million in grant money -- to reopen and expand existing public charter schools and create new ones. (With almost 60 percent of public school students now enrolled in charter schools, New Orleans has become a national model for their widespread use.)

The people of Algiers moved fast to claim part of the money. Within a month after the program was announced, community leaders and reform-minded educators drew up a plan for a network of charter schools on the West Bank under the umbrella of the Algiers Charter Schools Association.

Each school in the ACSA would have autonomy over budget and hiring decisions, and each would be accountable for results. After ferocious New Orleans-style political infighting, complete with secret meetings and temporary restraining orders, the Algiers charter plan was accepted and put into action.

When Behrman opened in mid-December, it was one of five brave new charter schools in Algiers. Lewis-Carter had been hired as principal just two weeks earlier from a field of more than 30 candidates.

"If there ever was an opportunity to get it right, this was our chance," she says. "All eyes were on us. We could not fail." Yet she had just days to recruit a staff and pull the school together.

In the spirit of change, many of the charter schools were hiring bright young idealists, generally from school districts outside of New Orleans. Lewis-Carter chose a different route: After interviewing more than 600 applicants with her team of helpers in one day, she hired veteran teachers from the immediate area.

"I needed folks who knew how to teach, were going to stick around, and had endured the Katrina experience and understood what the children had gone through," she notes, adding that the teachers were eager to return.

Hiring old hands was part one of her plan. Part two was getting them to buy into a radically different way of working. Like other schools in the Algiers charter network, Behrman was implementing the Teacher Advancement Program (TAP), a national initiative to help teachers improve their instruction methods by learning from experienced colleagues designated as mentor teachers and master teachers. (See the Edutopia.org article "A Charter School Charts Success with a Quality-Control Initiative.")

Last year, one of Behrman's master teachers, Brian Young, won a $25,000 Milken National Educator Award, which is given annually to 80 teachers nationwide. (Young is now an assistant principal at Behrman.) Under the program, high-performing teachers can earn incentive awards and potentially make more money than in the old public schools. But job security is history; everyone in the Algiers Charter School system, including Lewis-Carter herself, works on a one-year contract.

"It was a paradigm shift for many people," Lewis-Carter says, "but I knew that if we were serious about reforming, we'd have to take the self out of it. The time is over for people who are not going to do what's best for these children."

Part of her solution has been to make management decisions collaborative. When the school needed an additional first-grade teacher, Lewis-Carter met with the candidates, but it was the current first-grade teachers who conducted formal interviews and made the final choice, since they were the ones who would be charged with teaching their new colleague the Behrman way. And although the new system is more demanding of teachers, morale at the school is high.

"She's a big cheerleader," school librarian George Jeansonne says of her boss. "She seems to recognize what people do best and lets them do it. She never forgets to thank people."

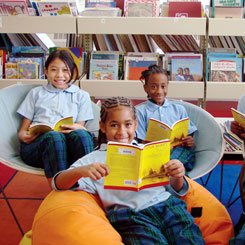

The challenges that teachers face also apply to students. "There are very high expectations, and nobody ever says, 'Oh, you poor little thing, you can't do better.' We always expect them to do better, and they do it," says Jeansonne. "And Mrs. Lewis-Carter expects the teachers to do their best, and they do it."

Faydra Alexander had worked with Lewis-Carter prior to Katrina and ended up teaching at Behrman for three years before moving up the ranks to become the local charter school association's TAP coordinator. She credits Lewis-Carter's leadership style and dedication to shared governance.

"She took the time to put teams of teachers together and brought out the best in us," Alexander says. "I never thought I'd be interested in any job outside the classroom, but in subtle ways, she gave me more responsibilities, and, before I knew it, I was in a leadership role."

Above-and-Beyond Philosophy

Like all public school students in Louisiana, children at Behrman face high-stakes assessment tests in fourth grade and eighth grade. Those who don't pass don't get promoted. In the first full year after the storm, the Behrman scores were among the best in the city; nearly the entire fourth grade scored at grade level or above proficiency in English and math. (At the elementary school that occupied the premises pre-Katrina, less than one-third of the students met that standard.)

In fact, 98 percent of fourth-grade students scored basic or above in English, and 96 percent scored the same in math. The school, which has an open-enrollment policy, is now competing on a level with schools that have many more advantages.

Impressive though these achievements are, they don't convey the warm, happy, purposeful atmosphere of the school Rene Lewis-Carter has created. She is never too busy to pay attention to individual children, says Mary Laurie, her mentor at Woodson and now a Behrman grandmother. "At the end of the day, every child wants to know that someone cares, to hear someone speak their name. Rene is a doer. She never waits for someone else to take responsibility."

Lewis-Carter's "above-and-beyond" philosophy extends to the children's cultural lives as well. The only difference between the students at Behrman and those from more privileged backgrounds, she will tell you, is experience and exposure. "I want everything for these children," she says.

Last spring, in a span of just a few days, students and parents alike went on a field trip to the Ogden Museum of Southern Art. There were also separate appearances by Behrman dancers and musicians in the Kids' Tent at the New Orleans Jazz & Heritage Festival, as well as an excellent showing at the middle school battle of the bands by the 70-odd-member school marching band, supported by majorettes, cheerleaders, and the Honeybees dancers.

Few school days pass by without Carter-Lewis exercising her extravagant powers of positive reinforcement. "I treat these children like kings and queens," she says. "I curtsey to them. I tell them all the time that they have the best-looking uniforms, that they have the best teachers, that they have the best parents and the best textbooks, that everything we give them is the best and that other schools wish they could have the same things we have.

"The children at Behrman believe that they're the best," Carter-Lewis adds. "And if they believe they're the best, they're going to put forth their best effort."

Lewis-Carter's achievements at Behrman have not gone unnoticed, but when asked whether she might want to ascend the administrative ladder -- become a superintendent, perhaps -- she almost shudders. Change, Lewis-Carter believes, needs to happen on the font lines, and that's at the school site. "This is where I belong," she says.

Last year, Lewis-Carter was the subject of a video intended to inspire school leaders. Producer Curtis Linton, vice president of the School Improvement Network, considers her to be an especially powerful role model because the demographics at her school are, as he says, as challenging as it gets. He adds, "I look at schools all the time, and Behrman blew me away. Kids don't get lost in that school."

In Lewis-Carter's own assessment, her greatest source of pride at Behrman has nothing to do with test scores. It is, instead, she says, "the burden I have placed on people. I want them to be burdened because I am burdened, and the moment it stops burdening me, I am out of here. If this does not burden you, you are in the wrong business."

Ann Banks has written for the New York Times Magazine, the Washington Post, and Vogue, and has published seven books for children.

Go to "Technology Workshops for Teachers Make Computer Connections" and "A Charter School Charts Success with a Quality-Control Initiative."