Public Education Faces a Crisis in Teacher Retention

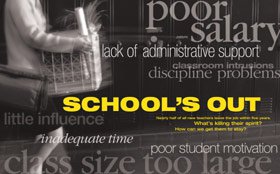

Nearly half of all new teachers leave the job within five years. What’s killing their spirit? How can we get them to stay?

Your content has been saved!

Go to My Saved Content.

It was late August four years ago when I sat down at a scratched wooden desk to begin my first teaching position. I was nervous. I knew that the job, if done right, wouldn't be easy. There would be long hours and little pay. But I also hoped that I could inspire kids the way my best teachers had inspired me.

What I didn't know then was that I wouldn't make it. Less than a year after facing my first classroom of thirty-two fidgeting tenth graders, I walked away and never came back -- to that classroom or to teaching. I became a statistic.

I entered the teaching profession full of idealism. After years of working as a journalist, covering the frenetic worlds of business and technology, I felt professionally unsatisfied. I spent my days writing about under-conceived companies and overpaid CEOs. I spent hours hyping the latest gadgets.

My roommate, a high school math teacher, suggested I sit in on a few of her classes. They were raucous, open, and energetic; I was fascinated. I had always loved language, and I saw teaching as a way to help kids appreciate it -- perhaps even love it -- as well.

By fall 2001, I made the career switch, completed much of my licensing credential, and was hired to teach tenth-grade English at Sequoia High School, in Redwood City, California, about 20 miles south of San Francisco. By the new year, I was gone.

Leaving So Soon?

Every year, U.S. schools hire more than 200,000 new teachers for that first day of class. By the time summer rolls around, at least 22,000 have quit. Even those who make it beyond the trying first year aren't likely to stay long: about 30 percent of new teachers flee the profession after just three years, and more than 45 percent leave after five (see charts, below).

What's more, 37 percent of the education workforce is over fifty and considering retirement, according to the National Education Association. Suddenly, you've got a double whammy: tens of thousand of new teachers leaving the profession because they can't take it anymore, and as many or more retiring.

When teachers drop out, everyone pays. Each teacher who leaves costs a district $11,000 to replace, not including indirect costs related to schools' lost investment in professional development, curriculum, and school-specific knowledge. At least 15 percent of K-12 teachers either switch schools or leave the profession every year, so the cost to school districts nationwide is staggering -- an estimated $5.8 billion.

Students from the lowest-income families suffer the most. Inexperienced teachers (those with less than three years on the job) frequently land in classrooms with the neediest and often the most challenging students. Beginning teachers frequently start their careers at hard-to-staff schools where resources may be scarce -- in other words, urban schools -- simply because there are more jobs available there.

It's a recipe for disaster for both teachers and students, says Barnett Berry, president of the Southeast Center for Teaching Quality, in Chapel Hill, North Carolina. Low-performing schools in high-poverty areas often cannot retain a critical mass of veteran teachers, says Berry. "Not only are teachers who are new to these schools more likely to be under-prepared, they're also more likely to be under-qualified."

The U.S. Department of Education confirms that teacher turnover is highest in public schools where half or more of the students receive free or reduced-price lunches. In California, for example, students in schools with large minority populations are five times more likely to face an "under-prepared" teacher (someone working on an emergency credential or outside of the person's subject area) than are students in schools with low percentages of minority students, according to a study conducted by SRI International and sponsored by the Center for the Future of Teaching and Learning in conjunction with California State University and the University of California.

A Frazzling First Year

Teachers quit for several reasons, but the one you'd expect to be at the top of the list -- salary -- typically isn't. Even though they start their careers earning roughly $30,000 (and fork out, on average, about $500 of their own money for instructional supplies), less than 20 percent of teachers who change schools or leave the profession cite salary as their primary job complaint, according to the National Center for Education Statistics.

More frequently, the reason is dissatisfaction with administrative support (38 percent) or workplace conditions (32 percent), according to the NCES's 2001 survey of 8,400 public- and private-school teachers. Poor administrative support, lack of influence within the school system, classroom intrusion, and inadequate time are mentioned more often by teachers leaving low-income schools where working conditions are more stressful; salary is mentioned more often by teachers leaving affluent schools.

Many of these reasons are just euphemisms for one of the profession's hardest realities: Teaching can exact a considerable emotional toll. I don't know of any other professionals who have to break up fistfights, as I did, as a matter of course, or who find razor blades left on their chair, or who feel personally responsible because students in tenth-grade English class are reading at the sixth-grade level or lower and are failing hopelessly.

New teachers, however naive and idealistic, often know before they enter the profession that the salaries are paltry, the class sizes large, and the supplies scant. What they don't know is how little support from parents, school administrators, and colleagues they can expect once the door is closed and the textbooks are opened.

"We don't put attorneys just out of law school alone on their first case, yet we put new teachers alone in the classroom for their first year and expect them to shoulder the same responsibilities as veteran teachers," says Kathleen Fulton, director for reinventing schools for the twenty-first century at the National Commission on Teaching and America's Future. "Our induction model creates impossibly high expectations."

New teachers are expected to assume a full schedule of classes, create their own lesson plans, and develop teaching techniques and classroom-management strategies in relative isolation. They are also expected to learn quickly the administrative ins and outs of the job, from taking attendance and communicating with parents to navigating the schools' computer network and finding the faculty bathrooms. The result: New teachers must weather a frazzling first year that many veterans come to view as a rite of passage.

It's also a recipe for early burnout. Attrition rates for beginning teachers who have not had strong teacher-preparation programs are much higher than for better-prepared colleagues.

"Not a day went by that I didn't go home and cry," remembers fourth-grade teacher Sue Manley of her first year. Manley, who graduated from Northwestern University with a master's degree in education, thought she was well prepared for her first assignment, teaching at a South Side Chicago elementary school. She had completed her student teaching the previous year at a grammar school in the same neighborhood and had spent four months volunteering as a classroom aide at another urban elementary school. Working with experienced teachers while she was still a graduate student and a volunteer had made teaching look easy to Manley. "Academically, I was prepared. Socially, professionally, and emotionally, I was not."

Like any new teacher, Manley needed to hone her classroom-management skills, but the pressures of managing a classroom solo for the first time were compounded by the lack of basic resources and administrative support. "We weren't allowed to use the copy machine [for handouts], so I had to stop at Kinko's every morning on my way to work," she explains. "There was never any toilet paper in the bathrooms for the kids, so I had to bring that, too." The last straw for Manley came in April, when she read a student's journal entry that described violent acts directed at her.

While Manley's situation may seem extreme, it's far from unusual. Other new teachers have reported similar feelings of isolation and impossible expectations.

"The amount of time I put into teaching was huge, and I still felt overwhelmed," says Pam Zabel, a former high school science teacher in Charleston, Rhode Island. Zabel, who holds a master's degree in education, says she was assigned a mentor teacher who was theoretically there for support and professional coaching, "but it was a very unstructured relationship -- I met with him maybe two or three times during the school year. For the most part, I was on my own." Zabel left teaching after her first year and is now a full-time mom.

"Mentally draining" is how Jim Treman, a former ninth-grade science teacher, remembers his induction to teaching. "I had no life for two years. I was constantly working. By the time Fridays rolled around, I was dead."

Treman worked as an architect for ten years prior to entering the single-subject credential program at San Francisco State University. His decision to become a teacher grew out of an experience he'd had teaching English while traveling in South America. He completed his student teaching as an intern, working as a full-time teacher while earning his credential. "I was reluctant to take the position at first because I had no clue what I was doing," says Treman. "I was promised a ton of support, which in the end turned out to be completely untrue. I was totally on my own."

Treman struggled to motivate his students; his assigned mentor, a physical education teacher, was unable to offer Treman curriculum guidance. Other science teachers seemed unwilling to share their materials. The school district's policy of laying off teachers in the spring and rehiring them in the fall didn't help. After his second year of teaching, Treman returned to architecture.

It Started Out So Well

Zabel and Treman, like me, were on their own. I always chalked up my experience to a bad case of unrealistic expectations. Maybe I was too spoiled by the fat and happy corporate world. Maybe I shouldn't have thought I would enjoy teaching my first year.

But as a student teacher, I'd had a very positive experience. I had taught language arts to seventh graders at a middle school in the upscale suburbs of San Francisco, and I was fortunate enough to have had an excellent mentor teacher. I designed what I considered to be fun, innovative lessons. I invited journalist friends to talk to the class about the persuasive power of writing. I organized grammar games and spelling contests. I brought in music from the '30s to illustrate the concept of story setting. I researched yoga and breathing exercises to help students take the edge off pretest jitters. (The entire class broke up laughing as we all tried to balance on one leg before the SAT-9s.)

But when the semester was over, Taylor Middle School wasn't hiring. Through my university's placement program, I landed a position at Sequoia. During the interview, the principal (who would be gone by that fall, along with the vice principal) told me my limited experience teaching seventh grade was "perfect" for teaching tenth grade at Sequoia. I was so naive that I didn't even ask why.

He promised plenty of support, recounted plans for a week-long new-teacher induction program before the school year started, and described the school building's recent remodel. I was given the names and phone numbers of two other English teachers willing to serve as my mentors that first year.

In practice, the induction program turned out to be something of a pep rally for new teachers, not a training exercise. The mentor teachers who had promised to help did what they could but were either teaching different grade levels or classes, and once the semester got under way had their own teaching concerns to address. In the end, I stopped asking for help. I was sinking, yet no one in the administration noticed. The principal, a former English teacher, observed my classes a few times and offered tips on my woefully underdeveloped classroom-management style, but she seemed unconcerned by my obvious lack of experience.

She told me not to worry and that tenth grade is the year when students who aren't going to succeed drop out. "High school is still a novelty for them in ninth grade," she said. "By eleventh grade, those that are left are the ones who've decided they want to graduate."

I didn't know what to make of that. Was I teaching students who were expected to drop out? As the semester progressed and I watched students struggle through assignments that were clearly beyond their ability, I grew more anxious and disheartened. I came home at the semester break and camped out on the sofa for three days, depressed and despondent. When the semester resumed, I emailed the principal my resignation.

Support Systems

There are some effective ways to soften the coarseness of the first year. What made the difference for Manley, for example, was a free two-year induction program sponsored by the University of Chicago's Center for Urban School Improvement. The New Teachers Network offers first- and second-year teachers at Chicago public schools personalized mentoring and online coaching that addresses a variety of issues, from classroom management to curriculum.

Several studies (and common sense) show that good mentoring programs can cut attrition rates by as much as half. Richard Ingersoll, a professor at the University of Pennsylvania and a respected researcher in the field of education, analyzed statistics from ten studies on mentoring and teacher induction to sort out what works and why.

His analysis, published in the American Educational Research Journal last summer, concludes that new teachers who receive no induction are twice as likely to leave teaching after their first year as those who receive all six of the supports his study identifies. These supports include having a mentor from the same field, collaborating regularly with other teachers in the same subject, and being part of an external network of teachers.

Other successful induction methods include a program called INTIME (Integrating New Technologies into the Methods of Education), which provides teacher candidates with videos of accomplished teachers in the classroom. The teachers in the videos give lessons in a variety of contexts, including multiage classrooms, alternative high schools, special education students, and gifted and talented programs. Such preparation can drastically cut teacher attrition rates. For people who are changing careers to enter teaching, schools like George Washington University offer assistive programs for mid-career entrants, including former military and Peace Corps attendees. One example is the school's Transition to Teaching Partnership, a collaboration with nearby Fairfax County Public Schools in Virginia.

But while mentoring and induction programs for new teachers are a mainstay in most states, not all programs are created equal. Of the twenty-eight states that have state-level teacher-induction programs, only ten actually provide funding for such programs, as well as mandating them, according to Recruiting New Teachers (RNT), a nonprofit organization that advocates national reform for teacher recruitment and development. That's a big problem. "Funding is critical, because mentors need to be given the time to work closely with new teachers," says Mildred Hudson, CEO of RNT, in Belmont, Massachusetts.

The regimen of the federal No Child Left Behind (NCLB) Act may help bridge the existing funding gap for some states. The first federal attempt to establish professional criteria for teachers, NCLB appropriates $2.85 billion over the next two years to help school districts recruit, develop, and retain "highly qualified" teachers (that is, those who meet state certification requirements and demonstrate knowledge in their core subject area, according to NCLB). Indeed, last fall the U.S. Department of Education unveiled a free professional-development Web site for teachers. Targeted mainly at K-8 instructors, the site offers streaming video of workshops conducted by other teachers, as well as supplementary course materials.

In addition, consideration and time must be given to professional development. For instance, seminars and lectures for beginning teachers were offered monthly at Sue Manley's school, but they were held on weekday evenings. Manley usually felt too busy and worn out after teaching all day to attend them. It's a situation many new teachers -- myself included -- encounter. When new teachers aren't granted release time for professional development, many end up going without. And eventually they just go.

Teachers who tough out the early years are often glad they did. Now in her seventh year of teaching, Manley has herself become a coach and a counselor for new teachers. Her advice: "Don't take things personally, be firm, and be calm. And take care of yourself. It does get better."

Claudia Graziano is a San Francisco-based freelance writer and a former high school English teacher.

Matchmaker

One organization working to redesign the way teachers are trained and recruited is the New Teacher Project (TNTP). Formed in 1997, this nonprofit partners with school districts and universities nationwide to create alternative routes to certification and to revamp slow, inefficient hiring practices. It also works to create innovative rural recruitment programs for states with large rural areas that face challenges in attracting high-quality teachers. A fundamental goal of TNTP is to find a better way to match up schools and new teachers. So far, the project has attracted and prepared more than 13,000 new teachers and launched thirty-nine programs in eighteen states. -- CG

Why Teach? We Asked and Were Overwhelmed

As we prepared this story on the alarming dropout rate among K-12 teachers, we decided to go to the source -- teachers and others involved in education -- and ask them a simple question: Considering the long hours, low pay, and poor support, why stay?

In early December, we sent out that email query. The response was overwhelming. In two days, we had 200 responses. In two weeks, we received more than 1,200. We heard from readers in Lake Havasu, Arizona, and London, England; in Frisco, Texas, and San Francisco, California. Current and former teachers lamented their chronically low pay -- that was expected -- but they also brought up their lack of autonomy, as classroom instruction is increasingly dictated by bureaucratic mandates.

Many, like Deb Methvin, a resource teacher at Silver Springs Elementary School, in Silver Springs, Nevada, spoke of feeling overwhelmed with the enormity of their tasks. "Sometimes there are semesters or a year that make you ask yourself, 'Why did I go into this profession?'" wrote Methvin. "There are the days when you're overwhelmed with paperwork, don't have enough time for planning lessons, need time to collaborate with your peers, have parents that want meeting after meeting and still are never satisfied, and put in a load of overtime that the administration seems to expect but never recognizes with praise or overtime pay."

Teachers balanced these frustrations with the job's many upsides, and often expressed the unmatched satisfaction of seeing a student comprehend a difficult concept and the special joy of connecting with a child who has pulled away from most adults. While some of the responses were predictable, others were refreshing and enlightening. Many were deeply moving.

Respondents offered suggestions on how to keep good teachers motivated, commenting on the important role an educator had played in their lives. Wrote Joette Daily, a special education teacher and liaison at Thomas C. Marsh Middle School, in Dallas, Texas: "I can really make a difference in the lives of students. I absolutely hated school when I was young. One teacher made a difference for me, and that experience completely changed my life. I remember thinking, 'She accepts me for who I am and for what I can bring to the class.' I wanted to be that kind of teacher."

Time after time, respondents thanked us for asking their opinion -- something they are rarely asked to share. Most also deeply believe that, despite the job's seemingly endless frustrations, teachers play an important role in a democratic society.

Lorien Eck, a visual-arts teacher at John Muir Middle School in South Central Los Angeles, spoke for many when she wrote, "The daily challenges are immense, yet the experience is soul empowering. . . . To see real-time results and evidence of positive change in the lives of young people makes the efforts -- despite the pay, the hours, and other drawbacks -- all worthwhile." -- RF

Strength in Numbers

Teachers represent one of the largest workforces in the United States. There are more educators than doctors, nurses, and lawyers combined, and according to the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, U.S. schools employ 3.5 million K-12 teachers. The education industry employs roughly 12.5 million people -- slightly fewer than health care, the largest employment sector in the country. -- CG

Wanted: Better Training

Many educators believe that schools need to completely rethink the way new teachers are trained. "One of the real problems with schools today is that they're the schools we had yesterday," says Kathleen Fulton, director for reinventing schools in the 21st century for the National Commission on Teaching and America's Future (NCTAF). "The existing training and recruitment model doesn't work for kids or teachers. Collaboration is key to developing good teaching skills, yet we're not set up for that in today's classrooms."

The answer, Fulton says, lies in radical change. She envisions clusters of new teachers working together in the classroom or alongside more experienced teachers and under the supervision of a national board-certified teacher.

Progress is being made toward that goal. The NCTAF is developing online learning communities that support novice teachers in rural and urban school districts. Called Teachers Learning in Networked Communities (T-LINC), the project will first target school districts in Washington, Colorado, Texas, and Maine. The idea is to bring together -- at least virtually -- new teachers, experienced mentors, and faculty members from institutions of higher learning to ensure that educators at all levels participate in the professional-development and mentoring process. --CG