How to End the Dropout Crisis: 10 Strategies for Student Retention

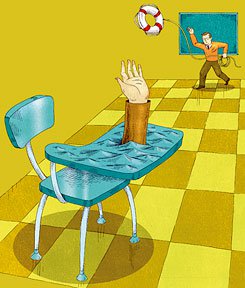

Proven tactics for keeping kids engaged and in school, all the way through high school graduation.

Your content has been saved!

Go to My Saved Content.

Are you sitting down? Each year, more than a million kids will leave school without earning a high school diploma -- that's approximately 7,000 students every day of the academic year. Without that diploma, they'll be more likely to head down a path that leads to lower-paying jobs, poorer health, and the possible continuation of a cycle of poverty that creates immense challenges for families, neighborhoods, and communities.

For some students, dropping out is the culmination of years of academic hurdles, missteps, and wrong turns. For others, the decision to drop out is a response to conflicting life pressures -- the need to help support their family financially or the demands of caring for siblings or their own child. Dropping out is sometimes about students being bored and seeing no connection between academic life and "real" life. It's about young people feeling disconnected from their peers and from teachers and other adults at school. And it's about schools and communities having too few resources to meet the complex emotional and academic needs of their most vulnerable youth.

Although the reasons for dropping out vary, the consequences of the decision are remarkably similar. Over a lifetime, dropouts typically earn less, suffer from poorer health as adults, and are more likely to wind up in jail than their diploma-earning peers. An August 2007 report by the California Dropout Research Project (PDF) detailed the economic and social impacts of failing to finish high school in the Golden State. The numbers cited in the report are sobering: High school graduates earn an average of nearly $290,000 more than dropouts over their lifetime, and they are 68 percent less apt to rely on public assistance. The link between dropout rates and crime is also well documented, and the report's data indicates that high school graduation reduces violent crime by 20 percent. And nationally, the economic impact is clear: A 2011 analysis by the Alliance for Excellent Education estimates that by halving the 2010 national dropout rate, for example (an estimated 1.3 million students that year), "new" graduates would likely earn a collective $7.6 billion more in an average year than they would without a high school diploma.

Mounting research on the causes and consequences of dropping out, coupled with more accurate reporting on the extent of the crisis, has led to increased public focus on what's been called the silent epidemic. And with that focus comes the possibility of more action at the local, state, and national levels to implement a mix of reforms that will support all students through high school graduation. Such reforms include early identification of and support for struggling students, more relevant and engaging courses, and structural and scheduling changes to the typical school day.

Decades of research and pockets of success point to measures that work. Here are ten strategies that can help reduce the dropout rate in your school or community. We begin with steps to connect students and parents to school and then address structural, programmatic, and funding changes:

1. Engage and Partner with Parents

It's an all-too-familiar story: Parent involvement declines as students get older and become more independent. But although the role of parents changes in secondary school, their ongoing engagement -- from regular communication with school staff to familiarity with their child's schedule, courses, and progress toward graduation -- remains central to students' success. Findings in a March 2006 report, "The Silent Epidemic," illustrate the importance of engaged parents throughout secondary school. Sixty-eight percent of the high school dropouts who participated in the study said their parents became involved in their education only after realizing their student was contemplating dropping out of school.

In Sacramento, California, high school staff members make appointments with parents for voluntary home visits, to keep parents engaged with their children's progress. This strategy -- which has so far been replicated nationally in eleven states, plus the District of Columbia -- includes placing as many visits as possible during summer and fall to parents of teens entering high school -- a critical transition point for many students -- to begin building a net of support and to connect parents to the new school. Staffers also conduct summer, fall, and spring home visits between and during the sophomore and junior years to students who are at risk of not graduating because of deficiencies in course credits, the possibility of failing the state high school exit exam (a condition of graduation), or poor grades. Visits in the summer after junior year and fall of senior year are to ensure that students are on track for either career or college. Early evaluations of the program by Paul Tuss of Sacramento County Office of Education's Center for Student Assessment and Program Accountability found that students who received a home visit were considerably more likely to be successful in their exit exam intervention and academic-support classes and pass the English portion of the exit exam. A follow-up evaluation of the initial cohort of students at Luther Burbank High School showed that the students both passed the exit exam and graduated high school at significantly higher rates. (Visit the website of the Parent/Teacher Home Visit Project.)

2. Cultivate Relationships

A concerned teacher or trusted adult can make the difference between a student staying in school or dropping out. That's why secondary schools around the country are implementing advisories -- small groups of students that come together with a faculty member to create an in-school family of sorts. These advisories, which meet during the school day, provide a structured way of enabling those supporting relationships to grow and thrive. The most effective advisories meet regularly, stay together for several years, and involve staff development that helps teachers support the academic, social, and emotional needs of their students. In Texas, the Austin Independent School District began incorporating advisories into all of its high schools in 2007/2008 to ensure that all students had at least one adult in their school life who knew them well, to build community by creating stronger bonds across social groups, to teach important life skills, and to establish a forum for academic advisement and college and career coaching. (Download a PDF summary of the results of a 2010 survey about Austin's advisory program.)

3. Pay Attention to Warning Signs

Project U-Turn, a collaboration among foundations, parents, young people, and youth-serving organizations such as the school district and city agencies in Philadelphia, grew out of research that analyzed a variety of data sources in order to develop a clear picture of the nature of Philadelphia's dropout problem, get a deeper understanding of which students were most likely to drop out, and identify the early-warning signs that should alert teachers, school staff, and parents to the need for interventions. After looking at data spanning some five years, researchers were able to see predictors of students who were most at risk of not graduating.

Key indicators among eighth graders were a failing final grade in English or math and being absent for more than 20 percent of school days. Among ninth graders, poor attendance (defined as attending classes less than 70% of the time), earning fewer than two credits during 9th grade, and/or not being promoted to 10th grade on time were all factors that put students at significantly higher risk of not graduating, and were key predictors of dropping out. Armed with this information, staff members at the school district, city, and partner organizations have been developing strategies and practices that give both dropouts and at-risk students a web of increased support and services, including providing dropout-prevention specialists in several high schools, establishing accelerated-learning programs for older students who are behind on credits, and implementing reading programs for older students whose skills are well below grade level.

4. Make Learning Relevant

Boredom and disengagement are two key reasons students stop attending class and wind up dropping out of school. In "The Silent Epidemic," 47 percent of dropouts said a major reason for leaving school was that their classes were not interesting. Instruction that takes students into the broader community provides opportunities for all students -- especially experiential learners -- to connect to academics in a deeper, more powerful way.

For example, at Big Picture Learning schools throughout the country, internships in local businesses and nonprofit organizations are integrated into the regular school week. Students work with teacher advisers to find out more about what interests them and to research and locate internships; then on-the-job mentors work with students and school faculty to design programs that build connections between work life and academics. Nationwide, Big Picture schools have an on-time graduation rate of 90 percent. Watch an Edutopia video about Big Picture Schools.

5. Raise the Academic Bar

Increased rigor doesn't have to mean increased dropout rates. Higher expectations and more challenging curriculum, coupled with the support students need to be successful, have proven to be an effective strategy not only for increasing graduation rates, but also for preparing students to graduate from high school with options. In San Jose, California, the San Jose Unified School District implemented a college-preparatory curriculum for all students in 1998. Contrary to the concerns of early skeptics, the more rigorous workload didn't cause graduation rates to plummet. Recent data shows that the SJUSD has a four-year dropout rate of just 11.4 percent, compared with a statewide average of 18.2 percent.

6. Think Small

For too many students, large comprehensive high schools are a place to get lost rather than to thrive. That's why districts throughout the country are working to personalize learning by creating small schools or reorganizing large schools into small learning communities, as part of their strategy for reducing the dropout rate. A 2010 MDRC report funded by the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation looked at the 123 "small schools of choice," or SSCs, that have opened in New York City since 2002. The report showed higher graduation rates at the new schools compared with their much larger predecessors. By the end of their first year in high school, 58.5 percent of students enrolled in SSCs were on track to graduate, compared with 48.5 percent of their peers in other schools, and by the fourth year, graduation rates increased by 6.8 percentage points.

7. Rethink Schedules

For some students, the demands of a job or family responsibilities make it impossible to attend school during the traditional bell schedule. Forward-thinking districts recognize the need to come up with alternatives. Liberty High School, a Houston public charter school serving recent immigrants, offers weekend and evening classes, providing students with flexible scheduling that enables them to work or handle other responsibilities while still attending school. Similarly, in Las Vegas, students at Cowan Sunset Southeast High School's campus can attend classes in the late afternoon and early evening to accommodate work schedules, and they may be eligible for child care, which is offered on a limited basis to help young parents continue their education. Watch an Edutopia video about Cowan Sunset High School.

8. Develop a Community Plan

In its May 2007 report "What Your Community Can Do to End Its Drop-Out Crisis," the Center for Social Organization of Schools at Johns Hopkins University advocates development of a community-based strategy to combat the problem. Author Robert Balfanz describes three key elements of a community-driven plan: First is knowledge -- understanding the scope of the problem as well as current programs, practices, and resources targeted at addressing it. Second is strategy -- development of what Balfanz describes as a "dropout prevention, intervention, and recovery plan" that focuses community resources. Last is ongoing assessment -- regular evaluation and improvement of practices to ensure that community initiatives are having the desired effect.

9. Invest in Preschool

In their August 2007 report "The Return on Investment for Improving California's High School Graduation Rate" (PDF), Clive R. Belfield and Henry M. Levin review both evidential and promising research as well as economically beneficial interventions for addressing the dropout crisis. Preschool, they argue, is an early investment in youth that yields significant economic results later on. In their review of the research on preschool models in California and elsewhere, the authors found that one preschool program increased high school graduation rates by 11 percent, and another by 19 percent. A 2011 article published in Science by researchers who followed participants in Chicago's early childhood education program Child-Parent Center for 25 years found, among other results, that by age 28, the group that began preschool at age three or four had higher educational levels and incomes, and lower substance abuse problems.

10. Adopt a Student-Centered Funding Model

Research shows that it costs more to educate some students, including students living in poverty, English-language learners, and students with disabilities. Recognizing this need, some districts have adopted a student-centered funding model, which adjusts the funding amount based on the demographics of individual students and schools, and more closely aligns funding to their unique needs. Flexible funding enables schools with more challenging populations to gain access to more resources so they can take needed steps such as reducing class size, hiring more experienced and effective teachers, and implementing other programs and services to support students with greater needs.

Although switching to this funding model does require an infusion of new dollars -- to support the added costs associated with educating certain groups of students without reducing funds to schools with smaller at-risk populations -- many districts have already explored or are using this option, including districts in Denver, New York City, Oakland and San Francisco, Boston, Chicago, Houston, Seattle, Baltimore, Hartford, Cincinnati, and the state of Hawaii, which has only one school district.

Roberta Furger is a contributing writer for Edutopia.

Retention Research: Studies About Keeping Kids in School

The following reports provide valuable insight into the causes of and solutions for the dropout crisis plaguing many of our schools and communities:

By analyzing a unique collection of both city and school district data sets over multiple years, researchers Ruth Curran Neild and Robert Balfanz were able to identify key characteristics of students most at risk for dropping out of school. The report describes the project and discusses the factors, such as grades and attendance, that are identified as predictive of high-risk students.

This 2006 report, sponsored by the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation, is based on interviews with young men and women, ages 16 - 25, who dropped out of high school. The findings debunk some of the commonly held myths about why students decide to drop out of school. (For example, a majority of the young people who were interviewed had at least a C average when they dropped out, and 47 percent reported that they dropped out because school was not interesting.) Embedded in these insights are useful strategies for addressing the crisis.

This 2010 report, published by the nonprofit education and social policy research organization MDRC, takes a close look at New York City’s 123 "small schools of choice," or SSCs. These schools are open to students at all levels of academic achievement, located in disadvantaged communities, and emphasize strong relationships between students and faculty. So far, they’ve also been successful at raising graduation rates.

Drawing on drop-out crisis research at the national level, as well as author Robert Balfanz's decade-long experience working with middle and high schools that serve low-income students, this report provides a unique guide to tackling the issue locally. It begins with strategies for developing a deep understanding of local needs and then guides readers step by step through the creation of a comprehensive plan to assist students inside and outside of school.

This 2011 annual update on a November 2010 report by Civic Enterprises, The Everyone Graduates Center at Johns Hopkins University, and America's Promise Alliance takes a look at the big picture. It is still grim, but getting less so: For instance, the number of high schools that qualify as "dropout factories" (schools that graduate 60 percent or less of their students) has declined from 2,007 in 2002 to 1,634 in 2009. The report compares current data with national goals and explores best practices through several in-depth case studies of struggling school districts.

Another report from Civic Enterprises and The Everyone Graduates Center at Johns Hopkins University, published in November 2011, asks how effective early intervention can be to prevent dropouts and build graduation rates. Early Warning Indicator and Intervention Systems (EWS) represent a collaborative approach by educators, administrators, parents, and communities to identify and support students at risk of not graduating. The report investigates the most successful EWS through case studies in eastern Missouri, Chicago, and Philadelphia, among others.