Online Classes Help Preserve the Navajo Language

A virtual high school lets students study a tongue that has a dwindling pool of teachers — and speakers.

Your content has been saved!

Go to My Saved Content.

When high school junior Reed Witherspoon heard about the Chief Manuelito Scholarship for high-achieving Navajo students, she knew she wanted it. Not only did the scholarship offer $7,000 a year for college but it also came with a requirement she was happy to fulfill: To be eligible, she'd have to take courses on Navajo language and government. The return to her roots -- Witherspoon has two grandparents who speak Navajo -- would make her family happy, and it would be a small step toward keeping an endangered language from disappearing. The problem was finding a way to study the language in the first place.

Rare Resource

Signing up for Navajo isn't like enrolling in a French class. The tribe has scattered around the country to the point where nearly half its population now lives off the Navajo Nation reservation, which covers parts of Arizona, New Mexico, and Utah. Witherspoon lives in Montana, and she doesn't know of a single other Navajo student at her school. As the pool of potential teachers dwindles with each generation, the problem facing Witherspoon and other would-be Navajo-language students comes down to simple numbers: too few speakers spread out over too many miles.

Enter the American Academy, an online high school that offers classes in both Navajo language and Navajo government, among other subjects. For the first time, students around the country don't need to locate a nearby teacher or wait for sufficient interest to build up at their school. On the contrary, a student can be the only person for a thousand miles interested in learning Navajo. All it takes is Internet access and a weakness for agglutinative languages.

"Navajo is one of our most popular classes, out of 233," says Rebekah Richards, the American Academy's senior vice president of academic affairs and the virtual school's principal. "When you have a subject for which you need to have such expertise, and there just aren't enough people with that expertise, you can leverage a tool such as online education to cross a large geographic distance."

The teacher doing the leveraging is Ron Singer, a Utah resident who grew up on the reservation. Singer's primary work is private security; teaching Navajo a few hours each week for the American Academy is "more like a hobby," he says.

"It's a dying language," Singer notes. "My own kids don't speak it. This class is designed to help keep it from disappearing. Our language is how we keep our culture and tradition intact."

High Tech, Low Trouble

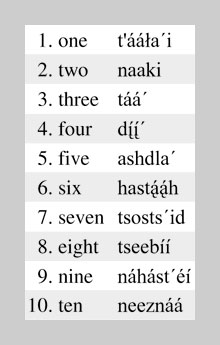

Neither the teacher nor students need anything higher tech than a computer with basic Internet access: Singer's primary tools are email and voicemail messages. He'll send out the latest vocabulary lesson -- on body parts, numbers, family relations, or colors or textures, for instance -- to his students, who later take a written test online.

Planting a seed:

Audio recording and email help Ron Singer teach Navajo to younger generations so that the number of people speaking the language may grow.

Credit: Courtesy of Alex KoritzWhen it comes to teaching pronunciation, Singer makes a voice recording, which the students can access online. The students, in turn, make recordings of their own by leaving voicemail messages at a designated phone number, which Singer assesses. All together, the classes involve 12 written tests and as many oral tests.For her part, Witherspoon says the format works well for a motivated student already enrolled at a traditional high school during the day. "For people who work better on their own, it's great," she says. "If you put your mind to it, you can probably get even more done this way; you're not waiting for other students. In that way, it's more one-on-one."

It would be premature to say the class, which has about 50 students, will single-handedly restore Navajo to linguistic prominence. But Richards says the feedback has been strong, and the implications are broad. Around 550 of the world's languages are spoken by fewer than 100 people, and about 200 are spoken by fewer than 10 people, according to the National Virtual Translation Center.

The late Peter Ladefoged, a professor at the University of California at Los Angeles and a leading authority on endangered languages until his death in 2006, predicted that half the languages in existence today will be gone within a century -- a common assessment in the field. If modern civilization helped bring so many ancient tongues to the brink of extinction, it might just produce the technology to save a few, too.

Lest aspiring speakers get ahead of themselves, Singer notes that students won't learn Navajo overnight. "It's one of the most difficult languages in the world, up there with Chinese and Finnish," he warns. "Will they speak it by the end? Oh, no! It's tonal, and it's got nasalized vowels -- you can study it for decades and never really be fluent."

Witherspoon was quickly struck by the language's complexity. "Unlike in Spanish and French, there are almost no cognates," she comments. "It's very unlike English. If I had to compare it to something, I'd maybe say it sounds Asian. You spend most of the first quarter just learning the sounds."

Cultural Revival

Still, Witherspoon says she intends to plow through and hopefully continue her study in the years ahead. "I've been out to the reservation and seen the culture, and it's amazing. It's like traveling to another country without leaving this one," she says. "I don't want something this important to a culture to vanish. It'd be like letting English die. No matter how small a population is, I don't think it's right to let a culture die."

The American Academy's Rebekah Richards says many of her school's students feel a similar draw to Singer's classes. Although the vast majority of students are high school age, she notes that a couple are in their 50s and "just always wanted to learn Navajo."

"It's a very personal thing for the students who come to us," Richards explains. "Being able to learn on their own terms is a powerful model and a powerful paradigm shift. It opens doors that weren't otherwise available to students. I think this is the epitome of what online learning can do."

Chris Colin writes the On the Job column for the San Francisco Chronicle and is the author of What Really Happened to the Class of '93.

Reversing Yesterday's Educational Mistakes

"The global village" -- it sounds cozy. But as globalization has awakened us to other cultures around the planet, it's also, in some cases, hastened the extinction of those cultures. Language often presents the clearest example of this effect. Smaller languages get swallowed by larger ones; Chinese, Hindi, English, Russian, and Spanish seep across borders and into institutions, and the less prominent Sarikolis, Parengas, and Clallams of the world recede further into the margins. It's a pattern Navajo-language preservationists hope to forestall.

The fight to save Navajo is often a struggle against mistakes made years ago. Today, students at the Tuba City Boarding School, on the Navajo reservation in Tuba City, Arizona, have the opportunity to study the Navajo language, history, and culture. But it wasn't always so. American Academy teacher Ron Singer attended the school decades ago, when the U.S. Department of the Interior ran it.

"We called it federal prison. They told us we couldn't speak our language," he says. "We had to learn English -- that's all. If you got caught speaking Navajo, they washed your mouth out with soap. It was terrible."

When the government wasn't banning the language, it was burning it. Singer describes with pride how his native language was the basis for the only code never broken by the Japanese military during World War II. But in seeking to protect that code, the U.S. government also burned a great many Navajo books at the time. As a result, the written record of the language grew even smaller -- not an insignificant loss for a language that was, until relatively recently, mostly oral.

Those who struggle to preserve Navajo takes solace in precedent; languages have occasionally been brought back from the brink: In the Republic of Ireland, the Gaelic-revival movement brought the once-vanishing Irish language to a point where 13 percent of the population speaks it. Twenty-five years ago, fewer than 1,000 people spoke Hawaiian -- also banned in schools at one point. That number has multiplied tenfold. And Hebrew might be the best example of what's come to be called language revitalization.

SIL International, a faith-based organization that works with the world's lesser-known languages, put the larger crisis of vanishing languages into perspective in one of its reports. "The number of languages listed for the United States is 238. Of those, 162 are living languages, 3 are second languages without mother-tongue speakers, and 73 are extinct," the report states.

It would be a rare thing for a highly complex, geographically disparate, and largely underrecorded tongue such as Navajo to resist the dominance of English. But for teachers such as Singer, who are working to spread its use bit by bit, the language is too special to let slip away.

"They didn't have a word for "cell phone," so they came up with a word that translates as 'the person who's spinning' -- because people on cell phones are always turning around, looking for a signal," Singer says. "So this is a language that's still evolving. And I think we've got a chance to stop it from vanishing." -- CC