The 5 Critical Categories of Rules

Your content has been saved!

Go to My Saved Content.In the responses to several of my previous posts, many comments focused on the debate of whether children need rules, or whether children are better off with free choice and have the ability to make correct decisions when free to do so. Summerhill by A.S. Neill is offered as a shining example of that school of thought. In a 1999 New York Times article "Summerhill Revisited," Alan Riding posited why the results of Summerhill were not as glowing as A.S. Neill described in his landmark book.

Choices and Limits

I fully agree that children need choices, a lot more than they get now in their school experience. Children also need limits to frame their choices. In fact choices without limits and limits without choices are both doomed to denying children the opportunity of learning how to act responsibly. The extreme of each position is this:

- Limits without choices: "Do what I say or else."

- Choices without limits: "Do whatever you want."

Neither of these options works in school, but when we combine the two, we have a symbiotic relationship that is designed to teach responsibility: "You cannot hit. But you can express anger. Here are three ways you can do it. Maybe you can add more."

Limits Are Rules

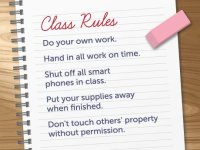

In school, we express limits as rules. A good rule is behavioral, clear and always enforced when broken. "Be respectful," for example, is a terrible rule because it is a value, not a behavior. It is important to teach students to show respect, but it's far too broad to enforce. It covers everything. "Raise your hand before you speak" is also not a good rule because it cannot always be enforced. Sometimes asking students to raise their hands is a bad idea. Hand raising works better as an expectation than as a rule.

Regardless of whether a school is open and free or traditional, limits or rules are necessary to teach students responsibility. I have identified five areas that I call critical categories which are useful when deciding what rules you need. Because rules work best when students have a say in their selection, I prefer teaching students what these critical categories mean, and developing rules together.

The categories are meant to be guidelines, not absolutes. Each category has its own focus. They add to the clarity of thought when considering the issues facing your school. Some issues, like those related to safety, cross categories between procedures (what to do if there is an intruder in the school) and social (keep your hands and feet to yourself). Worry less about trying to decide which is the best category for a rule and more about examining each category to see if it gives you ideas for making rules.

Critical Categories

- Do your own work.

- Hand in all work on time.

- Keep your hands and feet to yourself.

- Touch other students' property only with permission.

- Shut off all smart phones in class.

- Put your supplies away when you finish using them.

- When you hear me warn you, go immediately into the safe area.

- Do not offer food to a student who is fasting.

- Do not insult another student's religious clothing.

- I will let others finish saying something before speaking myself.

- I will do my homework without texting until it is finished.

All societies, whether free or not, need limits to protect the rights of the individuals who comprise that society. Schools, by the nature of their organization, goals and structure, require a different set of limits to be successful. The critical categories provide insight on the type of rules that are best for school environments.