The Gettysburg Address: Literary Nonfiction and the Common Core

Your content has been saved!

Go to My Saved Content.Although House of Cards on Netflix, the fictional Elmer Gantry and the preposterous Watergate cover-up all provide ammunition to those who view rhetoric pejoratively, rhetoric should be studied as a powerful tool for good. Winston Churchill composing speeches from bed comes to mind, as does the Gettysburg Address, a marvel of brevity more poignant than Winter Aconite, a speech that redefined the Civil War as a national fight for equality. The Gettysburg Address, composed by that hipster Abraham Lincoln, has never been more relevant, especially to the framers of the Common Core Curriculum Standards who appropriated Lincoln's address because of its literary rhetorical characteristics.

Literary Nonfiction and Intellectual Nutrition

The CCSS mandates that by the end of high school, 70% of what students read should be informational texts -- specifically, complex and non-narrative literary nonfiction. Furthermore, students should be able to identify central ideas and articulate their development, summarize, analyze, draw inferences, identify an author's purpose, evaluate the effectiveness of rhetorical features, and figure out the meaning of words. In short, the CCSS has reclaimed a technique popular in the 1940s, close reading, or sustained interpretation of, in particular, the wording of a text.

David Coleman, the senior architect of the Common Core, views the Gettysburg Address as the Platonic text amidst many others in the literary nonfiction genre, including the Declaration of Independence, Bill of Rights, Common Sense, Articles of Confederation, The Rights of Man, A Modest Proposal, MLK's "I Have a Dream" speech, and FDR's Pearl Harbor Address. Putting aside the conceit that we can align texts with specific ages when students' transactions with work depend on diverse life experiences, Appendix B of the CCSS provides a list of literary nonfiction "exemplars" arranged by grade level.

A cynic might point out that many of the important historical nonfiction exemplars suggested by the CCSS have no copyright restrictions, a boon for big textbook and testing companies. Furthermore, Coleman inexplicably denounces contextual instruction; the work is to be viewed as self-contained -- creating conditions similar to high-stakes tests and test preparation. That reading involves a transaction between readers' histories and culture with the text is ignored.

Rigorous classroom instruction is a good thing. But making students labor through arcane texts is not any more intellectually nutritious than reader response. To be clear, that the Gettysburg Address is worthy of study is undeniable. But close reading is only one pathway to understanding this masterpiece.

In a training session last summer, I observed 20 veteran teachers struggle to comprehend Lincoln's speech. Likewise, many students will initially need help comprehending literary nonfiction before they can pick up a text cold and successfully analyze it. Dave Stuart, Jr., a NYC teacher, in a blog about this perennial challenge asks, "How do I avoid over-teaching and under-teaching the complex texts we read in class?" Based on his interpretation of Kelly Gallagher's Deeper Reading: Comprehending Challenging Texts, 4-12, Stuart offers abundant support. "But there's got to come a point in each text where, in order to avoid enabling helplessness, I need to gradually release my students into independently grappling with the complex text in front of them." This approach is known as the gradual release of responsibility model.

How Do You Teach Literary Nonfiction?

Scaffolding approaches come in many shapes and sizes: Jot-Charting, SQ3R and Thinking Notes are common strategies for supporting comprehension and analysis. Simply having students mark up texts with questions and inferences before engaging in conversation is a good idea. ThingLink is a slick technology tool for annotation, particular when the "text" is a complex visual photograph.

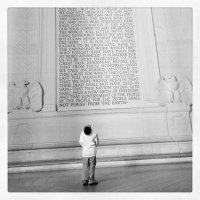

A weakness to these approaches is that they don't necessarily encourage students to care about a text like Lincoln's address. To motivate interest, start by letting students see copies of the Gettysburg Address or explore the Smithsonian's Interactive Gettysburg Address. Another hook might involve showing a dynamic snippet of Daniel Day-Lewis' preternatural performance of Lincoln ("I am the president of the United States of America, clothed in immense power! You will procure me those votes!"), but video should be used only as an entry point. President Lincoln's speech was barely audible to the audience at Gettysburg.

After capturing interest, have students use a speech analysis protocol, like Mike Putnam's Critically Analyzing a Speech or the speech analysis steps developed at Mounds Park Academy. My favorite Primary Source Analysis Tool, made available by the Library of Congress, teaches students to observe, reflect and collect. Click on the question marks for excellent prompts that help students think about those categories. For all of these tools, the steps listed should be rehearsed rigorously and explicitly so that students can analyze the Gettysburg Address without referencing the protocol.

There are dozens of Gettysburg Address learning activities that Google suggests, but most are dead links. Other lessons are targeted and useful, but only if your students don’t mind MySpace-era web design. Here are three: style analysis, vocabulary help and a Crayola Crayon-inspired rewriting activity.

Finally, EngageNY and Traci Gardner of ReadWriteThink share the two richest and most complete lesson plans on Lincoln’s speech.

What are your favorite learning activities for the Gettysberg Address? Or, more generally, how are you approaching literary nonfiction with your students?