A New Era for Student Assessment

Your content has been saved!

Go to My Saved Content.David Conley has just released a new report that highlights the importance of defining a new era for authentic student performance assessment. In A New Era for Educational Assessment, Conley argues that the time is ripe for a major shift in educational assessment, from an overreliance on standardized tests of math and reading, which tell us little about college and career readiness, to the use of multiple measures to gauge progress in learning the full range of content and skills that truly matter after high school.

When we started Envision Schools 13 years ago, we believed then -- as we do now -- that standardized assessments were necessary but insufficient for determining college and career readiness. It seemed obvious to us, as it does to so many educators, that bubble-in answers would only ever tell part of the story and that broader, richer assessments were critical to showing the full range of a student's abilities.

This is why we, in collaboration with the Stanford Center for Assessment, Learning and Equity (SCALE), created the Deeper Learning Student Assessment System (DLSAS). Schools and students needed more complete and better ways of demonstrating knowledge and skills along with ways of conducting authentic performance assessment for students.

Conley's report comes at just the right time; while we have heard endlessly about teacher, student, and parent frustration over standardized testing, about what those tests are missing, and how limited they are, the educational community has been too silent about alternatives. Conley offers several suggestions, and his report is essential to the larger conversation about performance assessment and what needs to happen in American schools.

Performance Assessment

But what exactly is "authentic performance assessment" and how do we know when it's happening? What are the reasons why we need to care about Conley's report?

Real performance assessment happens when we measure not just knowledge, but also skills and competencies that are inextricably related to success in college and career. This kind of assessment is concerned not just with content but also with real-world applications. Here's how you know when you have true, meaningful performance assessment happening in your classroom: when preparing for the test, taking the test, and then applying the skill in real life all look the same.

Consider the skill of parallel parking (or any other driving competency). How do you learn and practice it? By parallel parking. When you're getting a driver's license, how are you tested for this skill? By parallel parking. And what do you do with the skill after you pass the test? You parallel park.

The driver's license exam is a culminating assessment that results in the legal right to drive. It is not the only assessment in the process: The driver's permit exam (usually a written or electronic, standard multiple-choice test) assesses your knowledge of the rules of the road. It is an important step in the process, but not as important as demonstrating what you can actually do with your knowledge. That's where the performance test of actually driving and parking the car comes in.

Seen in this light, the need for real performance assessment in schools becomes more obvious. We can see exactly how important doing is to the process of learning, and we can easily agree that a driver's license should only be awarded to someone who knows not just the rules of the road but also how to operate a car.

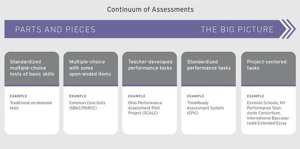

Conley's report helps us understand the continuum of the types of assessments and invites states to consider how to move their assessments from "Parts and Pieces" towards "Big Picture:"

Standardized assessments, even when they include open-ended questions and are performance-based, only give us part of the picture of a student's readiness for college and career success. Project-centered tasks ask students to practice and demonstrate command over the very skills they will need for the next step in their learning journey.

We think we need to move from having students drive toward their future while looking in the rear view mirror (tell what you know) to an "Eyes Forward" assessment (preparing them for the world to come). The following video created with Envision and the design firm IDEO illustrates this analogy.

Conley's Key Findings

1. College and career readiness depends on more than just academic knowledge and skills. Students also need to develop an array of personal and interpersonal competencies, as well as practical knowledge about the transition to life after high school. Examples include time management, perseverance, goal setting, self- advocacy, and even financial planning.

2. Schools can assess and teach a much wider range of competencies. Research shows convincingly that student motivation, persistence, self- discipline, problem solving, college planning, and other critical elements of college and career readiness can be assessed and taught effectively.

3. Traditional state tests are convenient but not very informative. Standardized, multiple-choice reading and math tests are reliable, familiar, affordable, and easy to administer. Unfortunately, they do not provide much useful information about students' progress toward long-term goals.

4. States are taking a new look at performance assessments. Today, a number of states are returning to performance assessments in order to get a better read on college and career readiness; the movement is already happening.

5. College and career readiness are best measured through a combination of assessments. Multiple-choice achievement tests have their uses, but so do diagnostic tests, performance tasks, informal assessments, and other means of tracking student progress. No single measure is sufficient to judge school performance and to guide instruction.

What Educators Can Do

Conley offers a wide range of recommendations for education stakeholders to follow; only a few are listed here. This is a starting point, a place for those of us who want to see real change happen to come together and make agreements. For a complete list of Conley's recommendations, see the full report. For now, let's take his advice and start with the following:

- Define college and career readiness comprehensively.

- Adapt federal education policy to allow greater flexibility in the types of data that can be used to demonstrate student learning and growth.

- Look for ways to improve the Common Core State Standards and related assessments so that they become better measures of deeper learning.

- Determine the professional learning, curriculum, and resource needs of educators to implement a new system of assessments.

The time is now for states and districts, charter management organizations, schools, and all of the educational initiatives to align with assessing deeper learning outcomes. To do so is to truly prepare our young people for college and career success in ways that will have real and positive impacts on their lives.