The Science of Fear

The amygdala is your brain’s 911 operator, triggering a hardwired reaction to danger. Fear is fun to learn about, but fear itself can hinder learning!

Your content has been saved!

Go to My Saved Content.What are you afraid of? Snakes? Turbulence? Spiders? Thunder? Speaking in front of a crowd?

All of us get scared, and all of us have different thresholds for what makes us afraid. Some of us enjoy the thrill of horror movies, and some of us (like myself) thought the fire scene in Bambi was too frightening.

Whatever it is that scares you, what we can agree on is that fear causes our bodies to react. Hearts pound. Palms sweat. Muscles freeze. Knees shake.

Well, if you are experiencing these symptoms, you have your amygdala to thank. The amygdala is the part of the brain that rests behind the eye and over from the ear. There are two of them, and they are tiny and almond shaped, but don't let the size fool you. Without the amygdala, humans would not have survived throughout history. The amygdala is a brain's alarm system.

Consider the amygdala as your own onboard 911 operator. It is waiting for bad news to come in. From the body's point of view, that bad news comes in the form of inputs like sight, sound, taste, touch, and pain, and this 911 operator then dispatches a signal for the body to respond by increasing the heart rate, blood pressure, or respiration. A surge of stress hormones will also be pumped into the bloodstream. And this chain reaction in the brain happens within fractions of a second.

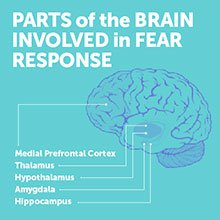

We can learn quite a lot from animals about how we respond when we are frightened. When an animal is in fear, its body freezes, the heart rate increases, and stress hormones enter into the blood. In the animal kingdom, this is helpful because a potential predator cannot see potential prey if it isn't moving. So remaining still can be a lifesaver. And the increased heart rate and stress hormones prepare the body to flee if all else fails. The amygdala, along with other parts of the brain (the thalamus, hypothalamus, and hippocampus), are key to our fight-or-flight reaction.

Parts of Our Body's Fear System

Brain Stem: triggers the freeze response

Hippocampus: turns on the fight-or-flight response

Hypothalamus: signals the adrenal glands to pump hormones

Pre-Frontal Cortex: interprets the event and compares it to past experiences

Thalamus: receives input from the senses and "decides" to send information to either the sensory cortex (conscious fear) or the amygdala (defense mechanism)

Your Amygdala at Work: A STEM Activity

When you get scared, your body releases stress hormones that increase your breathing rate and your pulse. Here lies a great STEM experiment (for healthy people only):

You'll need a watch with a second hand, and a stethoscope for taking a pulse. (One can also take a pulse by using two fingers, but remember not to use the thumb, since that has a pulse of its own).

In this class experiment, have students determine their normal heart rate. Later in the day, create a stressful event (like a fake drill, a fake pop quiz, or telling the class they're in trouble). Tell the students to take their pulse -- and that this was not a real event! They will notice that their pulse increased. Granted, this experiment is a bit cruel, but it's a great hook to discuss the science of the brain. Their increased heart rate and breathing will bring to bear the role of the amygdala.

While teaching about the amygdala might be wickedly fun, this part of the brain should not be a long-term guest in the classroom. Let's see why.

Fear and Learning Don't Mix

Oil and water. Milk and lemon. Toothpaste and orange juice. This is a list of things that don't mix well together. Another pair that we can add to that list is fear and learning. When we are in a state of fear, there are stress hormones in our bloodstream. Researchers have shown that low and medium levels of the stress hormone, called cortisol, improve learning and enhance memory, whereas high levels of the stress hormone have a bad effect on learning and memory. What that means is if you want to improve learning when things seem a bit stale in your class, you can create a bit of change like moving some chairs around or altering the environment slightly. The small change causes the brain to wonder, "What's up?" (Curiosity and fright are along a continuum.) However, an environment full of fear and anxiety will not improve learning. And this is not just in the classroom. Stress at home reduces learning, too. No one can perform well on cognitive tasks when their brains are being bombarded with fight-or-flight chemistries. A calm environment with a bit of variety increases learning, but a tense environment does not.

Fear is a funny thing. Some people enjoy it, but most of us don't. What is certain is that fear is the brain's amygdala showing its ability to protect us from danger.

Thanks, amygdala. Good looking out!