How Can I Be Sure I Know What Students Are Learning?

A teacher who found that reams of data didn’t capture students’ learning made these three tweaks to his quizzes and tests.

Your content has been saved!

Go to My Saved Content.It was at the end of my second year of teaching that I realized I was drowning in a sea of meaningless data. I was giving quizzes and tests, having students do projects and presentations, and even providing retakes and alternative assessments—but I couldn’t tell whether or not my students were really learning.

I had a collection of points that were calculated into a final grade, but if I’m being honest, even I didn’t know what that grade truly meant in terms of measuring learning.

This realization kicked off the most meaningful journey of my teaching career, one that took me down a path of fine-tuning assessments and grading reforms. When I started, I got overwhelmed changing my whole grading system to a standards-based approach, a Herculean task. My own experience and the research around the positive impacts of standards-based grading on motivation and student mental health have convinced me that this method is incredibly powerful (despite mixed research on the impact on student learning and achievement). But I also learned that there were smaller shifts I could make in how I designed assessments that would help me and my students know what they had learned and what they needed to work on.

Designing Targeted Multiple-Choice Questions

Multiple-choice questions tend to be frowned upon in assessment circles, but when designed well, they can have significant value for learning—specifically when they’re used for formative assessment and practice. The trick is in how they’re designed, especially the incorrect answers.

When I was first designing multiple-choice questions, I knew I needed a stem, a correct answer, and incorrect answers, preferably plausible ones. I would create quizzes with 10 questions and give students their score for those 10 questions. This, I thought, would give them information about their learning that they could use. But at some point I realized I was wrong about that.

Compare this alternative. Instead of making 10 questions, I now make one or two, but instead of just making each of the incorrect answers plausible, my goal is to intentionally make each one uncover a misunderstanding. These questions are individually a little harder to write, but because I write only one or two, my total time for writing a quiz is about the same as before, and the information I gain is more useful for me and my students.

Here’s an example:

The following statement contains an error in punctuation. Please choose the option that correctly fixes the error. My brother and I left our lunches and bags on the bus so we left school and walked to the bus garage to get our food.

A. My brother, and I left our lunches and bags on the bus so we left school and walked to the bus garage to get our food.

B. My brother and I left our lunches, and bags on the bus so we left school and walked to the bus garage to get our food.

C. My brother and I left our lunches and bags on the bus, so we left school and walked to the bus garage to get our food.

D. My brother and I left our lunches and bags on the bus so we left school, and walked to the bus garage to get our food.

Each incorrect answer reveals a misconception. Option A reveals a misunderstanding of compound subjects, option B a misunderstanding of compound objects, and option D a misunderstanding about compound verbs and verb phrases.

The key is to think about the common misconceptions students may have about a concept, and then to develop incorrect answers that uncover those points of confusion. Every question won’t have four choices—instead, you’ll create three, four, or however many incorrect answers may be necessary (within reason, of course).

Students can use this information to identify what learning to engage in next. I can share a document with links to instructional videos that address the four misunderstandings, and as soon as students get their results, they can engage in the learning they need in that moment.

Creating Assessment Blueprints

What about scaling this strategy up to a full test? This is where assessment blueprints come in. An assessment blueprint is simply a map of the learning that each question targets. In my experience, these are especially helpful with assessments that come with a curriculum as opposed to ones I write myself, as they allow me to take what I’ve been given and be intentional about identifying what each question is focused on. Here are three examples that show what these assessment blueprints could look like.

This strategy doesn’t require any changes to the assessment itself, but it creates opportunities to use the assessment results to help students engage in more learning because it shows them how the questions connect to the concepts they’ve been learning.

For example, if questions 1, 3, and 5 all connect to the same concept, a student who misses a couple of those questions knows precisely which concept to focus on. When I used this strategy with students, we would take some time to analyze the results, and then students could identify the specific concept or two that they needed to work on. I would provide resources and activities, sometimes pulling small groups to focus on a couple of concepts so that students could immediately reengage in the learning.

My goal was to ensure that a student struggling with a concept didn’t just have to sit with a vague sense of incompetence, but instead had actionable information for future growth.

Organizing Assessments Around Learning Progressions

The assessment blueprint helps align existing assessments to learning outcomes, but what if you’re building a new assessment? How could you better design it to really target the learning you want students engaged in? For me, this is where assessments organized by a learning progression can really shine.

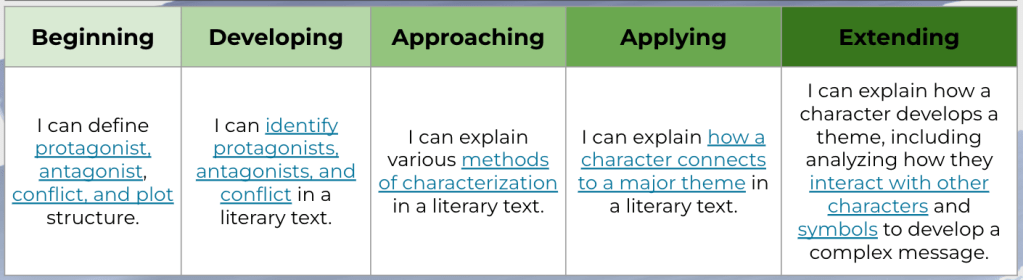

A learning progression is a scaffold that breaks down a complicated standard or learning outcome into manageable steps. Here’s an example:

I used learning progressions in my classroom for a while and saw plenty of benefits from them. Students were able to self-assess where they were in their learning much more accurately because of the clarity and concreteness of each phase in the progression. And I was able to differentiate more efficiently by embedding instructional videos directly into the learning progression and having students use them for targeted instruction. I was also able to align my instructional sequences more effectively simply because of the thinking I put into the learning progression.

However, it wasn’t until I started developing assessments aligned to my learning progressions that I saw the true value in the progressions. The first time I took an assessment and reorganized the questions, adding some as needed, to align with a learning progression, it was amazing to watch how clearly students were able to connect the assessment to the learning that they were engaged in.

Here’s an example of what that looked like: Organizing assessment questions to align with learning progressions makes it very clear for students what learning they need to focus on next, and it helps to build students’ self-efficacy, as the early questions help them see that they have the background knowledge to be successful on the rest of the assessment.

What I found when I started redesigning my assessments to match my learning progressions was that I had many of the questions I needed already—I just had to move them into a different order and identify which phase of the progression the questions addressed.

My students’ ability to use their assessment results vastly improved when I did this. Previously, if I were to ask students after an assessment what they needed to work on, I would get vague, general answers. With this strategy, my students were able to very precisely articulate what they were going to work on next in their learning.

Often when we think about improving our assessment practices, it feels overwhelming—as though we have to change our entire grading philosophy and redo our entire curriculum. What I have found is that smaller changes like the ones I describe here can have big results, helping both me and my students know what learning has happened and what needs to come next. These steps to ensure that my assessment practices are more forward-focused and learning-centered will always be worth the effort.