Big and Small Strategies to Harness the Power of Peer-to-Peer Teaching

The brains of kids who are teaching peers go into overdrive—boosting retention and understanding. Here’s how to leverage this effect in your classroom.

Your content has been saved!

Go to My Saved Content.Peer pressure gets a bad rap.

It can lead to all kinds of trouble, of course, but when it comes to activities like peer-to-peer teaching, the pressure to exhibit competence and explain things accurately actually drives deeper learning, a 2024 study that peeked inside the brains of student teachers concludes.

College students were outfitted with futuristic caps studded with optical sensors to measure neural engagement, and given 10 minutes to digest a multimedia lesson about the Doppler effect. The students assigned to explain what they’d just learned in their crash course to a classmate felt the weight of the task: They reported significantly higher levels of anxiety than students asked to simply re-read the lesson or explain it to themselves.

But these peer-teachers also experienced “greater and more complex brain activity”in social and cognitive processing centers, researchers found—leading them to perform nearly 50 percent better on tests of the material than students who simply restudied it.

The findings line up with the well-documented benefits of what researchers have dubbed the “protégé effect,” a strategy where teaching recently learned information to peers pushes you to organize your thoughts more clearly, identify knowledge gaps, correct mistakes, and improve your comprehension of a concept.

“There are few shortcuts to mastery, but the protege effect appears to be one of the most effective ways of accelerating our knowledge and understanding,” concluded science author David Robson, in a recent article for The Guardian.

According to Robson, the brain boost we get from teaching others arises “as much from the expectation of teaching as the act itself.” For example, a 2009 study found the strategy works even if we’re teaching virtual characters on a computer screen.

“If we know that others are going to learn from us, we feel a sense of responsibility to provide the right information, so we make a greater effort to fill in the gaps in our understanding and correct any mistaken assumptions before we pass those errors on to others,” Robson says.

There are a lot of ways you can implement this powerful strategy in your classroom. We’ve assembled a few activities that are easier to pull off, and others that require more time to facilitate—and place more responsibility on students to organize and present their thinking—but can also lead to more robust results.

Think, Pair, Share: This is one of the simplest forms of peer-to-peer teaching and can be used as a brief break during a lecture or lesson. To get the most out of this versatile strategy, consider spending some time at the start of the year to model the optimal dynamics for social learning. Peers listening to explanations should ask clarifying questions and offer counter-points to help tease out further understanding—a process that will aid both themselves and their partner, research shows. As students share, circulate to ensure everyone is participating, and pose questions that might jumpstart lagging conversations.

Three Before Me: Turn the protégé effect into a classroom rule with this low-lift approach. When students have a question about something they’re learning, have them ask at least three peers for help answering the question before coming to you. This simple rule creates opportunities for students to practice teaching recently learned information to each other, and can help students identify and autonomously address knowledge gaps they might have, says elementary school teacher Angela Coleman. “They’re capable of answering their own questions and knowing what to do if they can’t instead of always relying on an adult.”

Jigsaw Groups: This strategy requires a bit of advance planning and should probably be used when addressing foundational knowledge, but it tends to maximize many of the protégé effect’s benefits. Break students up into small groups and give each student a separate piece of the lesson plan to become experts on and teach to their peers.

For example, if you’re learning about atoms in a science class, assign students in a group to separately study protons, neurons, or electrons and then bring the group back together so each student can teach their newly learned section of the material. Together the group learns the whole lesson by combining their smaller bits of knowledge—like combining the pieces of a puzzle—and each group member should be able to synthesize the materials in a quick, written essay or verbal quiz.

AI Chatbots: If students aren’t able to work in groups, or with peers, generative AI can help them leverage the protégé effect, Robson writes. He recently used this strategy himself, practicing Spanish by prompting ChatGPT to take on the role of a curious Spanish student “who would like to hear what I have been learning.” He used a voice-recognition function to practice both spoken and written language. By the end of a 10-minute session, “I felt that I had embedded more of the vocabulary, grammar and turns of phrase than if I’d done an hour of textbook exercises,” Robson said.

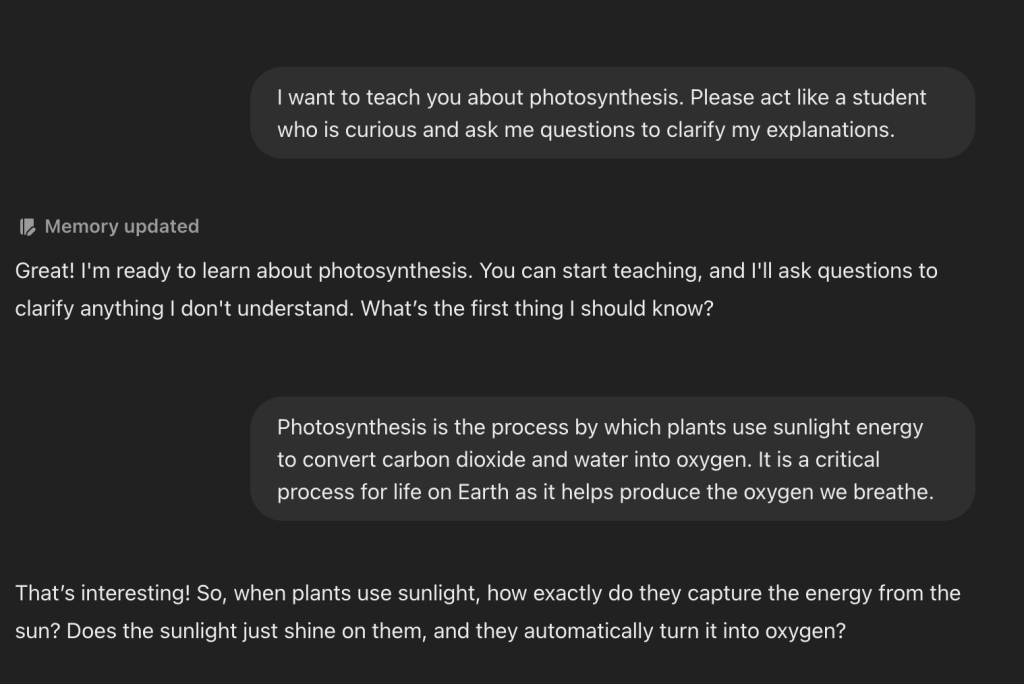

To explore this idea in your classroom, ask students to type a prompt like the following into ChatGPT: “I want to teach you about [insert concept]. Please act like a student who is curious and ask me questions to clarify my explanations.” By running through the task yourself several times, you may be able to scaffold the process enough to yield high-quality results.

I recently tried this with photosynthesis and, acting as the student, provided my bot with a rudimentary explanation: “Photosynthesis is the process by which plants use sunlight energy to convert carbon dioxide and water into oxygen. It is a critical process for life on Earth as it helps produce the oxygen we breathe.”

In response, the bot asked me a good follow up question that tested my knowledge—and quickly identified gaps in my understanding.

Video Lectures: Another student is not even required to be present to stimulate the benefits of the protégé effect—just the thought that peers might one day listen to your explanation of material is enough, a 2023 study confirms. College students who had just studied a text about enzymes were asked to demonstrate their understanding by either creating concept-maps, writing down as much information as they could remember, or preparing and delivering a short, video-taped crash course on what they’d just learned. Researchers told the latter students that their videos would be viewed by an audience for “educational and research purposes”—which was enough to help them retain more information than their peers, and generate better questions about what they were learning.

To replicate this, follow the lead of second grade teacher Courtney Sears, who utilizes platforms such as Seesaw and Google Classroom to have students create “tutorial” videos that demonstrate recent learning aimed at peer viewers. Her kids are receptive to the approach, since many of them already “watch tutorials on YouTube to learn things like how to advance in a video game or do a dance move, and they’re eager to make this type of video to share with their friends,” Sears says.

Middle school math coordinator Alessandra King uses a similar activity in upper-grade math classrooms by asking groups of students to choose a complex problem, solve it, and create a video detailing their problem solving strategy and why they chose it. King tells her students that the videos will be kept and used to “benefit current and future students when they have some difficulties with a topic and associated problems.”

Inanimate Objects: It can feel a little awkward, but teaching an inanimate object should also work. “Rubber duck debugging” is popular amongst computer programmers, for example, and involves them explaining their code line by line as well as their goals for the code, Robson said, eventually identifying any possible issues. “By verbalizing their thinking process, they find it easier to identify the potential problems in their program.”

You can practice this by asking students to explain their learning or their steps to solving a problem to their own version of a rubber duck.