4 Ways to Boost Students’ Self-Efficacy

These strategies help students see what they have learned so they believe they can be successful in school in the future.

Your content has been saved!

Go to My Saved Content.So often I hear people in education say, “We want to build confident learners.” That always gives me pause for a couple of reasons. First, the students most confident in their learning are often the ones who know the least—a phenomenon known as the Dunning-Kruger effect. Second and more important, wanting confident learners doesn’t require anything on the part of the educator. For me, confidence is joining the ranks of terms like grit and resilience that are great in theory but are often used to put expectations on students instead of analyzing the system of education or how our classrooms function. Expecting confidence doesn’t inherently require anything intentional in terms of instructional design.

This is why I have come to focus more on the term self-efficacy, which takes the opposite approach to a similar goal. When we focus on confidence, we emphasize a belief and hope that it leads to outcomes. Self-efficacy, on the other hand, focuses on outcomes to drive beliefs. In essence, self-efficacy involves intentionally providing students with evidence of early success to help them build the belief that they can be successful in the future.

Self-efficacy has been a powerful focus for me because it helps me to be more intentional as a teacher. It requires me to be mindful of how I structure assessments, feedback, etc., to provide students with evidence of their successes early on to help them see potential future successes.

I struggled with this early on because I learned very quickly that superficial or fake “evidence” of success (things like inflated praise) ended up harming students’ belief in themselves in the long run—if they even believed it. I realized I had to be intentional about developing methods to provide evidence of actual success early on for my students.

Here are some of the most important ways I did this.

Scaffolded Assessment Sequences

Often, the first assessment I gave my students was on the new content in a unit, whether that was a preassessment or the first formative assessment as we learned the content. The problem was, this often meant that students experienced failure early on if they didn’t know the content yet, and because this was their first feedback about the unit, it communicated a message of incompetence that they would carry throughout.

Instead, I began to focus on providing an assessment early on that covered the background knowledge needed to be successful with the new content. For example, if my goal was to have students write an analytical paragraph about character development in a text, instead of starting there, I would start by asking students to define protagonist and antagonist, explain what conflict is in a text, or label a typical plot structure diagram. This gave me a chance to check in on the background knowledge that students needed to grasp the new content, and it provided students an opportunity to experience competence, knowing they had the foundation they needed to be successful with the coming content.

There were students who struggled even with this type of initial assessment. It then became my goal to ensure that these students learned that content quickly and experienced success before we moved on too far. I needed to get them to that initial goal first instead of trying to get them all the way to proficiency on the new content as their first step.

Tiered Assessments

It’s not only the order in which assessments go that matters—the order in which the questions go on the assessments matters as well. There is evidence to suggest that ordering questions from least difficult to most difficult can increase performance on tests, and doing so has also been linked to increased motivation and persistence through difficult exams.

The idea here is twofold in terms of the impact on students. First, initial questions help to activate prior knowledge for students, priming their brains for harder questions later. Second, this ordering provides students with a tangible reminder of what they already know so they can tap into their own sense of self-efficacy during the assessment.

To create a tiered assessment, you can think about Bloom’s Taxonomy as you work. Typically, the “remember” and “understand” levels of questions will end up being the less complex elements of the content—students will be able to be successful on these. However, I would often take this a step further when designing assessments, and the early questions were often background knowledge from previous grade levels that was connected to the concepts we were working on.

Feedback Portfolios

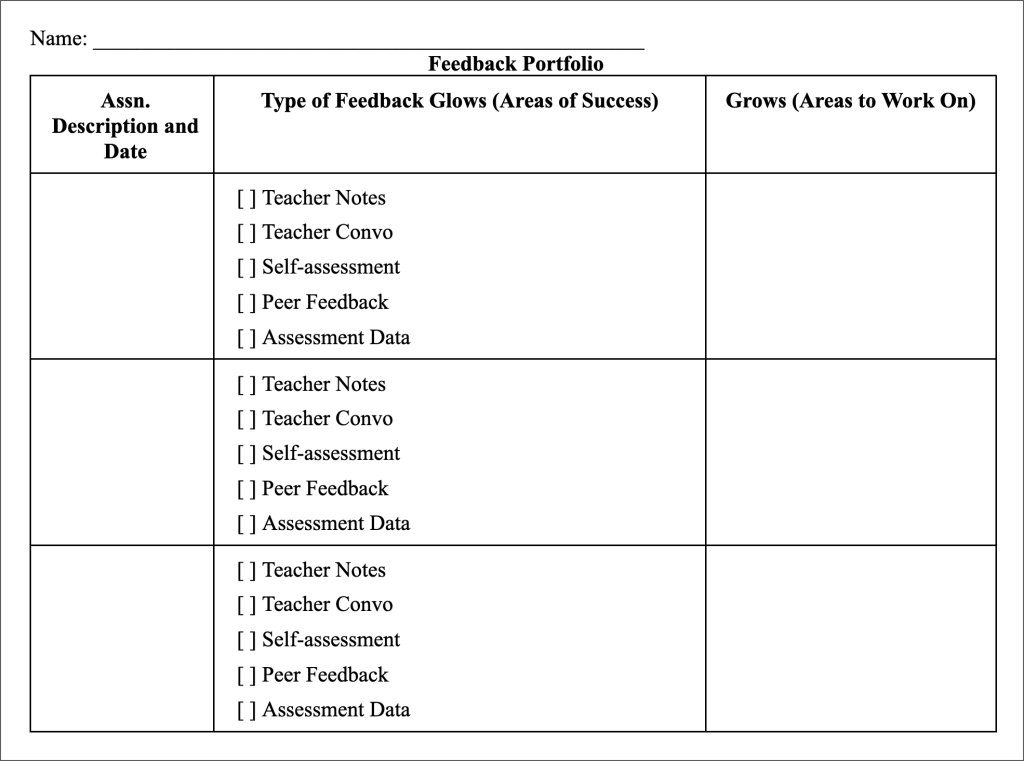

When I provided feedback to students, it was often frustrating to me that they wouldn’t use it beyond the assignment it was connected to. I figured that I could either continue complaining about this or come up with a solution. To start, I began delaying the grade, putting a grade on their work only after they had interacted with their feedback, but what really made a long-term difference for me and my students was setting up a feedback portfolio.

The idea behind this was that anytime a student received feedback—whether it was feedback from me or a peer on a piece of writing, or an assessment result—they would record it in this feedback portfolio. My purpose was to ensure that they were using the feedback and not forgetting about it after turning in an assignment. What ended up happening was more interesting: Students began to see concepts that had started in the “grows” column move over to the “glows” column. This was a vehicle to support students’ self-efficacy—they were easily able to see evidence of learning and growth that would have been quite difficult to see if they hadn’t gathered the feedback together in one place.

A Simple Way to Have Students Gather Evidence of Success

Portfolios were very intimidating to me for a while because so much of what I saw about them required a major overhaul, so that a student’s entire grade was based on their portfolio. What I learned was that you can implement portfolios in much smaller ways and still have a positive impact on the learning that students are engaged in.

For example, if you’re working on three skills in a unit, you can have a document where students copy and paste examples of times they did well on each of those three skills. That’s it. It doesn’t have to be any fancier than that, and by just having them do that, you can get students into a mindset of looking for evidence of success—the foundation of building self-efficacy with students.

I remember a student I had a few years back whose primary language wasn’t English. He was struggling a bit with his writing and would often hang his head about it, but when we started the practice of gathering his best sentences and passages into his portfolio, it made a huge difference in how he approached a piece of writing. He had evidence of success to believe he could be successful again in the future.

These are a few ways to help build up students’ sense of self-efficacy in the classroom—the key, though, is to be really mindful about how we are structuring experiences for students to celebrate their success as evidence that they can be successful in the future.