A Case of Rural Equity: Coding in Remote Kentucky

A teacher works to sustain a computer science program at a high school in the heart of Appalachia.

Your content has been saved!

Go to My Saved Content.Belfry High School teacher Stephanie Younger and her students recount a 90-mile trip from their small Kentucky town for a computer training session the way some people recall family vacations.

“Heaven and I gave the boys dating advice,” Younger says of soft-spoken senior Heaven Charles and the three teenage boys who traveled with her, crammed into Younger’s tiny Kia Rio hatchback, singing along to the radio and playing Nintendo. “It was funny, and awkward at times, but we definitely bonded.”

Lured by the promise of access to new technologies, the five piled into the car and headed west on Route 119, whisking past the stretch of businesses that mark the outskirts of this remote town of about 3,000 people before emerging into a hilly countryside draped in fog and dotted with small country churches—the spiritual seats of coal-mining towns in Appalachia.

The pastoral landscape surrounding Belfry rarely reveals the damage from the recent collapse of the coal industry in the region, and then only in the form of dilapidated houses and shuttered storefronts. As in West Virginia—the border is only four miles from Belfry—demand for coal in northern Kentucky declined sharply as the nation turned to less-expensive natural gas to generate electricity. At the same time, automation eliminated the mining jobs that sometimes paid workers with high school diplomas more than $70,000. In a single, ruinous decade, the area shed 13,000 jobs—and its population declined by nearly 10 percent.

It didn’t take long for the other shoe to drop. In a pattern that has become all too familiar in small-town America, psychological devastation followed grimly on the heels of the economic downturn. A federal investigation of neighboring Williamson, Kentucky—once known as the “Heart of the Billion Dollar Coalfield”—revealed that over the course of a decade, nearly 21 million opioid-based pain pills were shipped to two pharmacies just four blocks apart, a fact that earned the town the nickname “Pilliamson,” ground zero of the national opioid epidemic. In 2016, drug companies settled with the state for more than $35 million for their role in the crisis.

But inside Younger’s car on the trip to Hazard, Kentucky, concerns about poverty, drugs, and unemployment were not top of mind. The students were excited to be traveling to a regional educational co-op where they would try out motion-capture suits, experience virtual reality, and learn about ways to pursue careers in computer science, one of the fastest growing, most lucrative fields in the country.

Fits and Starts: Building a Computer Science Program

A 180-mile round trip for a day’s training is not unusual for Belfry, which is situated along the Tug Fork River in an isolated corner of northeast Kentucky, almost four hours southeast of Louisville, the state’s largest city, and 90 miles southwest of Charleston, West Virginia.

“It takes forever to get anywhere,” Younger says, reflecting on the difficulties of bringing a rare skill set like computer science to a rural school.

She had already made the trek to Hazard for the initial training by the Kentucky Valley Educational Cooperative, which began expanding coding education in the region in 2015. Training from AdvanceKentucky—a statewide nonprofit located in Lexington, a six-hour round trip for Younger—allowed her to add two Advanced Placement computer science courses. She traveled to Louisville periodically for further professional development.

Distance isn’t the only issue, though; Belfry High’s computer science program faces other obstacles typical of rural districts. Computer science is not yet an established priority at the school, recruitment of trained teachers is difficult, and budgets are chronically tight—the program would not have started at all without the external funding, according to Younger.

Still, Younger remains committed to the cause. “I truly believe that having access to computer science in high school has changed the lives of many of my students,” Younger insists, taking the long view. “The number of once-in-a-lifetime opportunities and doors that have opened for my students warms my heart.”

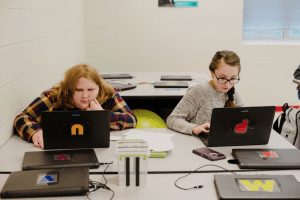

Once up and running, the computer science classes caught on quickly at the school of roughly 600. Realizing that she needed a clear pathway for interested students, Younger added a new AP course in 2016 and another this year. Today, 45 students take courses in coding, game design, and principles of computer science.

A former student, Shelby Bailey—now a freshman computer science major at nearby Eastern Kentucky University—remembers rough patches in those early classes as Younger and the students learned the subject together. “We were guinea pigs,” Bailey says with a laugh. “It was the first time, so of course there were going to be rough patches.”

Senior Heaven Charles got hooked after her first exposure during Code.org’s Hour of Code, a program designed to introduce students to coding. Charles recalls thinking, “This is cool. Do we have classes like this? I want to take them.”

Charles has followed through, taking all the coding classes currently offered and even informally tutoring others when needed.

Although no one in her family has gone to college, Charles says her divorced mom has been supportive of her dream, telling her, “We’ll find a way.” Charles has already been accepted to Eastern Kentucky University, a 15,000-student institution three hours from Belfry, where she plans to major in computer programming and game design.

A Fragile Kind of Equity

In the last four years, the number of high school students taking computer science classes in the region’s 22 school districts has ballooned from 25 to about 800. That’s still a tiny percentage of the region’s 50,000 students, but it’s enough to instill hope that one day students here will see coding as not just a legitimate profession but a skill that will allow them to remain in the area.

Younger admits that her dream would be to see a groundswell of coding students help lure a company to relocate to the area. But even having a single student leave college with a computer science degree and return home to work remotely “would make my year,” she says.

Younger thinks that somewhere between five and 10 of Belfry’s graduating class of about 140 students go on to study computer science each year—a number she hopes will increase. Because she has trained other educators nationwide on teaching computer science, Younger was asked to help write the state’s first computer science standards; Kentucky will consider formally adopting the curriculum next spring.

Building the program at Belfry, though, remains an annual fight because of declining enrollment at the school and a dwindling budget. The school has only four laptops capable of handling game design demands, so if Younger offers that course, she doesn’t have a computer of her own to use during class. And adding more computer science classes will tax the teaching staff, spreading an already lean corps even thinner.

District decisions compound the problem, including a recent plan to reduce high school graduation requirements. The state demands 22 credits, and Belfry had previously required students to earn 26 to graduate.

“A lot of these kids don’t know what they want to do. They will take the easy path, and it will hurt them,” Younger says. “We need this program at this school.” The average salary for computing professions in Kentucky is more than $68,000 annually—$25,000 a year higher than the average salary in the state.

Younger may struggle to maintain her program, but her stress is not apparent when she teaches a group of 30 students how to frame questions in a way a computer can process. And her students match her enthusiasm: During Younger’s planning period, senior Jared Mueller can be found in the back of her empty classroom, connecting various computer components together in an experiment.

Mueller moved to Belfry from Cleveland at the beginning of ninth grade and says the lack of alternatives for entertainment in the area—“There’s only movies or bowling,” he says—makes pursuing coding for gaming more attractive.

He found that he loved the challenge of coding immediately. “It’s so satisfying to beat a prompt,” he says, referring to solving a computer problem quickly.

One of Younger’s former students, Jacob Williams, remembers the sense of community he felt as he and his peers tried to “learn this whole computer language by ourselves.” Williams continued his computer science education at the next level: He is a second-year computer science major at Eastern Kentucky University.

Beyond the basic knowledge he picked up at Belfry, he’s grateful that the exposure to coding in high school showed him how this subject could become a career.

Looking back on taking part in Belfry’s first computer science classes, Williams says, “I like to think that talent and ability is evenly distributed across the world, but sometimes opportunity isn’t.”