The Tech Skills That ‘Digital Natives’ Are Missing—and How to Help

Students are growing up in a world filled with technology, but explicit instruction, support, and guidance are needed to help them use it in ways that meaningfully amplify their learning.

Your content has been saved!

Go to My Saved Content.In front of me in line at the grocery store, a small child no more than 3 years old sits in her stroller holding a cell phone. Her plump, eager fingers dance across the screen—flicking through stacks of icons, clicking the YouTube app, tapping on a video about farm animals, and then adjusting the volume with ease. This is a digital native at work.

Coined by author and former educator Marc Prensky in 2001, the term “digital native” describes the young people born after the 1980s into a technologically rich landscape: “They have spent their entire lives surrounded by and using computers, video games, digital music players, video cams, cell phones, and all the other toys and tools of the digital age,” Prensky wrote.

Somewhere along the way, it became a widely held belief that these digital natives were developing advanced skill sets simply by using technology on their own. With the proliferation of personal computers in the late 1980s, the in-school computer lab went the way of the dodo, eventually replaced with district-issued one-to-one devices and an assumption that kids just knew how to use them. Schools started to phase out explicitly teaching skills that were once mainstays in computer classes—everything from how to type properly on a keyboard to creating a spreadsheet in Microsoft Excel.

The result? More students had access to devices than ever before, but teachers over the years began reporting critical skill gaps: classrooms full of students hunting and pecking at keys to write an essay rather than typing with fluency, centering a title at the top of a Word document by holding down the space bar, placing the entire contents of their email in the subject line, and resetting their passwords every class period.

The State of Students’ Skills

While students might grow up surrounded by technology, they’re not innate digital learners, says tech coach Debbie Tannenbaum. That’s an important distinction.

“Our kids know how to consume using technology, but that doesn’t mean they know how to think critically using technology or create using technology,” she says. “We give a kid a device, and we expect them to just know how to learn with it, but it requires a very different skill set.” While anybody can press play and watch something, Tannenbaum wants students to engage with technology in active ways “to help amplify their learning or take their learning to that next level.” That’s something they need to be taught how to do.

In 2018, an international study examining the computer, information literacy, and computational thinking skills of more than 46,000 eighth-grade students at 2,200 schools across 14 countries determined—as it had in their 2013 report—that “young people do not develop sophisticated digital skills just by growing up using digital devices.”

Though six years have passed since then, “you cannot expect that there are completely opposite pictures,” explains Dirk Hastedt, executive director of the International Association for the Evaluation of Educational Achievement, which released the analysis. Digital natives are a “myth,” he says, and we can’t keep assuming that students will pick up technology skills purely through osmosis: “We’re creating a digital divide and we’re leaving some students behind. That’s definitely something to worry about.”

A Path Forward on Teaching Digital Natives Tech Skills

Students need help developing digital competencies, Hastedt says: “We ask them to create PowerPoints. We ask them to find information on the web. We ask them to use computers in their further learning. If you don’t teach them how to do these things, and if we don’t expose them to these learning experiences, then that’s not fair.”

Teachers don’t need to take it upon themselves to teach every technology skill in isolation. Instead, technology use can be integrated across the curriculum and supported by a bank of community resources and collaboration with other students and school staff.

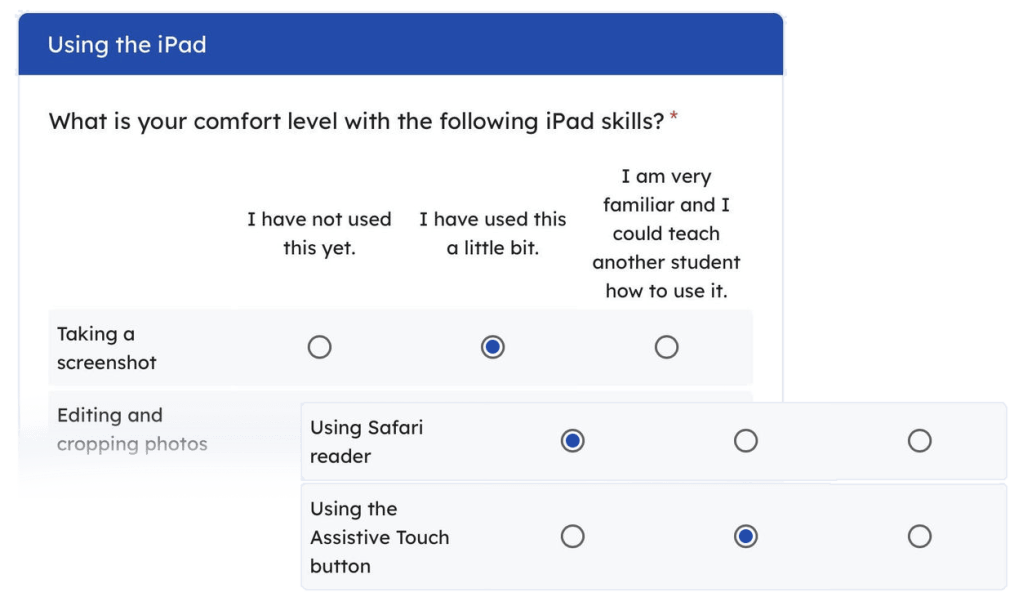

Establishing a baseline understanding: Talking to students is always a great place to start, says Megan Ryder, a multisubject, multigrade teacher.

Before planning lessons and projects, Ryder gives students a technology survey where they rate their comfort level using apps like Book Creator, Google Docs, and Keynote, as well as their mastery of skills they’ll use in her classroom. “Please be completely honest,” she writes to students in a short blurb at the top of the page. “It is fine if you don’t know how to use the tools or apps listed on this form.”

Leveraging the experts in the room: Middle school teacher librarian Shannon Engelbrecht encourages teachers to find the tech experts in their classrooms and name them: “Acknowledge them and get kids used to the idea of being an authority on something,” she says.

Encourage students to show off their skills and pass their knowledge on to their peers. “I had to build their understanding that it’s OK to share and teach each other,” Ryder says. “I do a lot of promoting: ‘Why don’t you show your classmate on your device how you were able to draw that line or how you were able to make the text bigger?’”

After teaching a skill, Ryder asks students to raise their hands if they feel comfortable demonstrating it to a classmate. Those students become a valuable resource if anyone needs help or a quick refresher on a skill, though it’s worth reminding kids to teach rather than do things for one another. Over time, this promotes an environment where students help each other organically and rely less on you as the sole source of information.

Building students’ capacity to struggle: In the wake of the Covid-19 pandemic, some teachers have reported a rise in learned helplessness as well as a loss of agency. “Kids’ zone of productive discomfort shrank quite a lot because it was such a terrible time, so we’re really working to increase that,” Engelbrecht says.

When students come to her for tech help, she starts by asking, “What have you already tried?” Often the answer is “Nothing”—a perfect opportunity to encourage them to troubleshoot a bit on their own. “What’s one thing you think you could try?” she asks next. While this approach may be met with blank stares, Engelbrecht says it’s important to challenge students to be a bit more curious about their devices.

Alternatively, walk a student through the steps that will solve their problem, but have them do the work themselves. “I’m going to describe to them how to do a hard reset of [their] Chromebook,” she says. “I’m really just constantly handing it back to them and helping them grow that productive discomfort. Sometimes they think, ‘Why can’t you just do it for me?’ Because I’m not always going to be here. And once they know how to do it, they can show everybody in all their classes.”

Teaching skills in context: A few years ago, Engelbrecht’s school tried having teachers play short videos each week in advisory that reinforced different tech skills. “Less than half the teachers did it,” she says, noting that they didn’t feel it was a good use of time. Plus, students weren’t then turning around and flexing those muscles. Teaching the skills in context is much more effective. “Let’s say you’re doing a research project and kids need to be able to find websites again—teach them how to bookmark a site and then have them bookmark the two best sites they found,” she says.

Struggling to see where to fit this type of skill-building into a lesson? Instead of completely reenvisioning an assignment, start small. Engelbrecht suggests using the SAMR model—substitution, augmentation, modification, and redefinition—as a guide. The easiest level is a substitution, she says: “Rather than having a student write a note to you in a journal, you substitute by having them send that to you in an email.” Over time, as students’ capacity to work with the technology increases, you can move on to the more complex levels.

Curating the resources that students need: “If we want students to seek out information from sources other than the teacher, we must make sure those resources are available,” writes Andrew Miller, a director of curriculum and instruction.

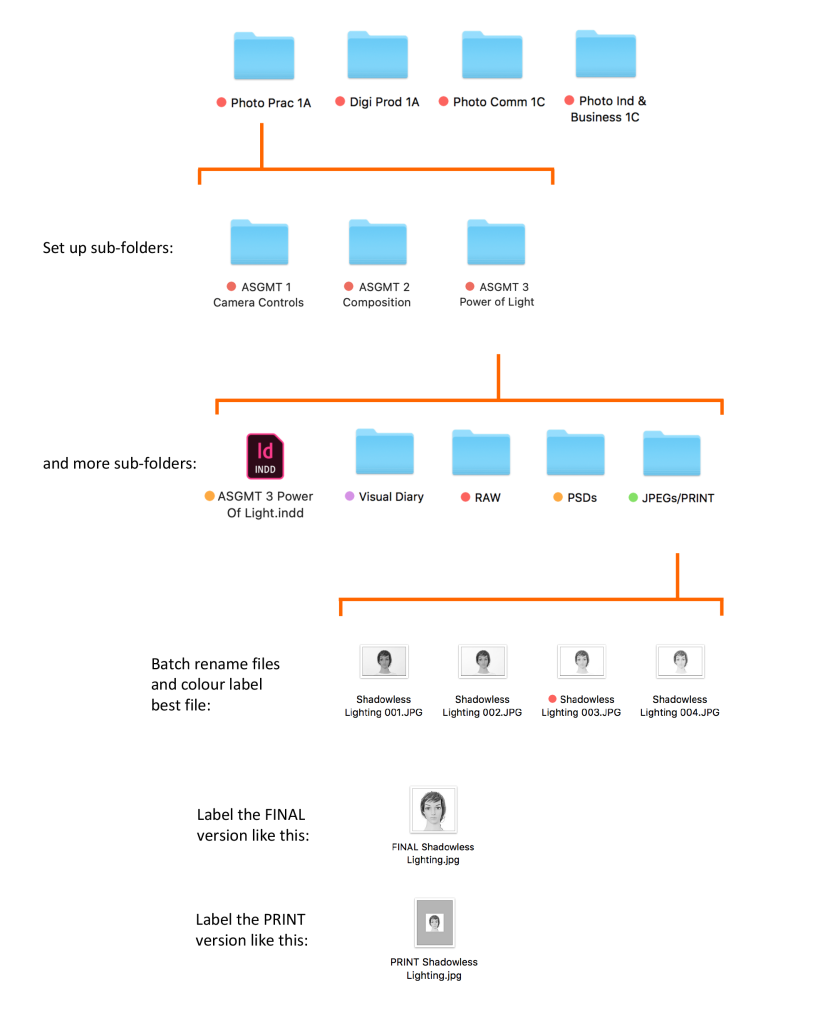

When introducing students to a tool like Photoshop or InDesign, Tricia Falkner—a senior lecturer at a polytechnic institute in New Zealand who works with students ages 17 to 55—now provides her classes with a verbal explanation while she shows them her screen, as well as a recorded video tutorial and a handout with screenshots that they can refer to as needed. Students who know the technology well can move quickly, while those who don’t feel supported in learning.

These resources are shared throughout Falkner’s department, so no single educator is responsible for creating or updating them. At Engelbrecht’s school in California, the approach is similar. Whenever she hears teachers talking about a skill they wish students had—like bookmarking a website, email best practices, or caring for their Chromebook—she’ll create a screen-cast video tutorial. “I’m not the only one that makes them,” she says. “We have school counselors, English and art teachers that make them, and we just aggregate them all in the how-to videos section. If a teacher says, ‘How do I teach kids how to do X?’ there’s a video for that. You can show it in your class, then can show the kids how to find it again later.”

Leading the charge: When teachers are asked what they’d like training on, many say they’re interested in professional development on innovative ways of using computers and how to teach the skills that students need to be successful, says Hastedt. “We can’t expect teachers to teach computer skills if we don’t teach them how to do that,” he explains. “For some teachers, I think it’s overburdening them, and that’s not fair to the teachers to say, ‘Well, just teach it,’ without helping them.”

School leaders should be leading the charge, writes education technology consultant Victoria Thompson for ASCD. They can establish themselves as technology leaders by “asking good questions to get to the heart of student and teacher technology needs” and “actually using the technology that their educators employ in their classrooms.” Thompson suggests identifying and leveraging technology experts within your building—students and adults—to help lead small professional development sessions or create professional learning communities focused on technology.

Library media specialist Andy Spinks, for example, isn’t a digital native himself but is a valued technology expert in his school’s community. Spinks’s father and grandfather were car mechanics, and from a young age he learned the importance of tinkering and understanding how things work. Now, he says, people “come to me for help with technology because I’m just stubborn and persistent; I try different things and keep hammering at it till I make it work.”