A High School Turns to Former Students to Address Racism on Campus

Alumni at a predominantly White high school opened up about the racism they experienced as students—and helped change the culture of the school.

Your content has been saved!

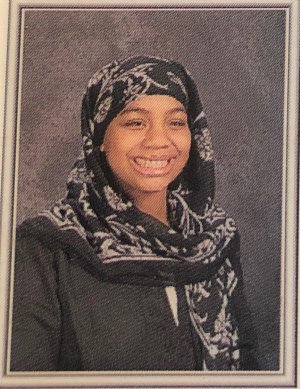

Go to My Saved Content.Growing up as a person of color in a school district mostly devoid of diversity can be a lonely experience. Jamila Beesley knows this because she lived it.

Located in the suburban outskirts of Albany, New York, her alma mater—Bethlehem Central High School—has always been a predominantly White school in a predominantly White district.

From an early age, Beesley, who is Muslim, was conscious of the uniqueness of her identity within the community. She remembers peers and adults pointing out her differences. By high school, she had endured a number of slights and insults—some of which stemmed from ignorance and misinformation, while others were deliberate and malicious.

It was common for her to receive comments from peers about the “marker on her hand,” referring to her henna, for example. A teacher once perpetrated a myth about Islam in the classroom, telling students that women in Muslim countries aren’t allowed to receive an education because of their religion. And as she got older, during the post-9/11 era, classmates would ask if Beesley’s family was part of the Taliban.

“People, mostly boys, tended to pass off their racism under the guise of dark humor or ‘just joking,’ [but] there were a lot of terrorist jokes thrown around,” Beesley recalls. “At a track meet my sophomore year, a group of guys on the team kept asking me how to build a bomb, because of course, due to my background, I must have known how.”

At the time, Beesley didn’t have the language to articulate what she was experiencing or how it made her feel. Calling it out, she thought, would be fruitless: All of her friends were White and had no frame of reference for her experiences. But college changed that. In fall 2018, she began her freshman year at Brown University surrounded by more people of color than she had ever seen in her hometown. Some students had also grown up in predominantly White communities and shared similar reflections.

“There was this really weird unloading of trauma that I didn’t even know was trauma and learning a lot of terminology... now I had words to talk about it,” Beesley says of her growing awareness. “And I think I was really, really angry.”

After the 2020 murder of George Floyd sent shockwaves through the nation, young people of color like Beesley began to connect both the subtle and overt microaggressions in their schools and communities to the public, racialized violence happening throughout the country. Using social media as a megaphone, they created more than 40 Instagram pages about the discrimination they faced—a painful record of marginalization particularly within the predominantly White K–12 schools they attended.

In Bethlehem, Beesley and other alumni wondered how and when their former school district would acknowledge what was happening in the nation—and within their hallways. Some began sending letters to the district recalling microaggressions and racism they had experienced and called for systemic improvements at the school.

“When conversations about White privilege do not occur in predominantly White communities, the experiences of people of color become delegitimized and ignored,” Beesley wrote in her letter to the administration. “These experiences had been so normalized by the culture in the school district that I didn’t fully comprehend how wrong they were until I went to a place where people of color’s voices weren’t drowned [out].”

An Environment of Voluntary Sharing

Bethlehem Central High School is nestled in an upper-middle-class hamlet known for its spacious homes, tree-lined roads, and cozy small-town feel. It’s not uncommon for many families to have attended and graduated from the school for generations.

Over the years, demographics in the community have slowly shifted. Two decades ago, roughly 95 percent of the student population was White, and very few students of color attended district schools; today, 15.7 percent of the district’s more than 4,200 students are students of color.

As the area has changed, conversations surrounding how to support all students—not just the racial majority—have become increasingly urgent, according to Dave Doemel, principal at Bethlehem Central High School. Until alumni spoke up, Doemel says, staff were unaware how deeply structural racism had become ingrained in the culture of the school.

“We didn’t know what we didn’t know,” says Doemel. “Once we became more aware of the many realities present to our students and staff alike in our building, we really felt the urgency to address the issues with a holistic approach.”

Because alumni were the first to break the ice, Bethlehem school leaders believed they could also be integral to changing the dynamics. Their hope was that with direction and stories from young adults close in age, current students might feel comfortable enough to share too—an approach that research shows is effective in getting youth to open up.

“I think one of the problems that Bethlehem had was they tiptoed around a lot of these issues,” Beesley says. “If it made people uncomfortable, they were like, ‘OK, then we’re not going to talk about it at all.’... [After] George Floyd, I think a lot of places recognized that they couldn’t not talk about this.”

In fall 2020, the district organized a series of virtual community-building sessions with a volunteer group of eight alumni, most under 30, and current students. Over the next four months, upwards of 200 11th- and 12th-grade students participated in 18 pilot sessions on Google Meet. These sessions, which were recorded, were meant to provide current students with a forum to discuss race and difference without singling anyone out.

Damaris Skelton, a 2010 BCHS alum who is African American, wanted to ensure that participating students understood the impact their words and actions can have on their classmates of color after experiencing isolation in high school herself. As a transfer student from New York City, Skelton felt she didn’t fit in anywhere at Bethlehem—not with students of color and not with the White students because of the cliquey nature of the student population.

“That ‘sticks and stones may break your bones, but words will never hurt you’ saying is very untrue,” says Skelton. “We’re here because of those words.”

‘Feeling of Not Fitting In’

The first sessions were spent establishing norms and building rapport with students. Nonconfrontational prompts got the ball rolling. Students were asked early on to recall a time when they might have felt excluded, in order to build a sense of community and shared experience in the room.

“There are so many students who, not necessarily in terms of ethnicity but because of some aspect of their identity, feel marginalized,” says Nick Ferguson, a social studies teacher at the school who facilitated several sessions. “They felt—even though we weren’t specifically talking about anything other than race—they identified with that feeling of not fitting in.”

While teachers like Ferguson and counselors were present to help, they let alumni and students lead the discussion. Connections were forged quickly, and as students became more comfortable, the conversations shifted to more serious topics like microaggressions, implicit bias, and stereotypes. Some students admitted to their own assumptions and perceptions of others based on race or background, while alumni had an opportunity to reflect more critically on their experiences.

While she admits it’s easier to focus on fond memories of the school and the community, Jannah Umar—a 2008 BCHS alum who is African American and Muslim—challenged herself in the sessions to view her past through a more discerning lens. She reflected on how peers viewed her when she started wearing a hijab in middle school, along with the many subtleties she felt over the years—and the ongoing sense that she was different.

“You’re going to get more of the microaggressions,” explains Umar, now a licensed social worker. “No one’s necessarily going to outright call you the N-word. You’re going to get those slow, stab wounds.”

As the 45-minute-long sessions went on, some students started to realize and openly talk about things they had said and done to peers of color that may have had negative, harmful ramifications. Some reached out to connect privately with alumni. Umar remembers one girl who stayed on the call after her classmates left and asked if they could chat.

“She said, ‘Can I speak to you about my experience? I really connected to what you were saying,’” Umar recalls. It gave her hope that she and other alumni were able to provide mirrors for students to see their own experiences reflected back to them—and windows into the lives of others.

Moving Forward, Together

Principal Doemel believes the sessions with alumni provided administrators and educators with valuable insight: a better understanding of the school’s climate, and how they impact and can improve it.

“I’ve learned that it doesn’t matter how experienced I am or where I’m pulling climate data from—the teachers and the educators will listen to students,” says Doemel. “Not only do the students feel valued and feel like their voices are heard, but the teachers hear that; that hits them.”

Ferguson says he has used the experience in the sessions as a time to reflect on past student interactions throughout his nearly three-decades-long teaching career. “I had these students who, to me, seemed like we had a good rapport, and they were well-adjusted and super-successful here as students. And I just was oblivious to how painful the experience was,” he says.

Moving forward, school leaders say they will continue to collect feedback from some of the student-centered groups within the high school and work to provide students with additional opportunities and forums for them to speak freely, such as a virtual diversity, equity, and inclusion workshop series called “Bridging the Divide” for BCHS students and their families.

As school districts throughout the country grapple with similar challenges, rebuilding trust with students and families should be in the forefront of school leaders’ minds—and they should be committed for the long haul, say experts such as Michelle Burris, senior policy associate at the Century Foundation—a nonpartisan think tank focusing on racial equity in K–12 education. This means being mindful of staffing, language, curriculum, and embedded policies and practices—especially when it comes to multilingual learners, who are often left out of important conversations regarding race.

“Schools should seek input from teachers and students separately, and ultimately practice critical humility: being aware of what school leaders do not know and being able to listen to the needs of BIPOC [Black, Indigenous, people of color] students and families,” Burris explains. “Ultimately, schools must know that disrupting racism in education is a journey and will not happen overnight.”