It’s Important to Talk About Learning Accommodations With Your Students—Here’s How to Do It

From metaphors for elementary school kids to mindset shifts and graphic organizers for teens, here are teacher-tested tips for normalizing learning accommodations across grade levels.

Your content has been saved!

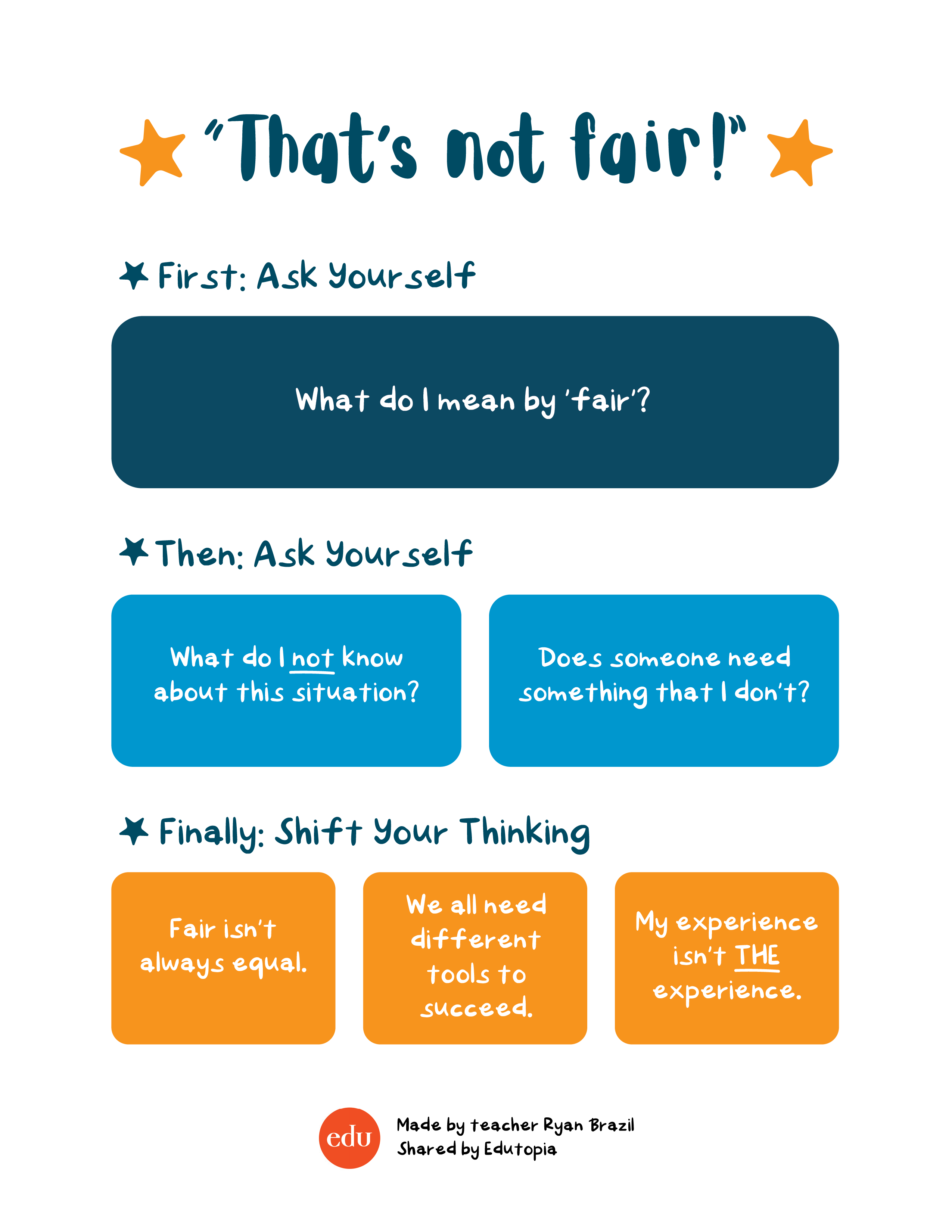

Go to My Saved Content.Ryan Brazil is teaching a lesson about fairness—at least that’s what it seems like.

First, she asks a tall child to retrieve a ruler she’s stashed above her whiteboard; he succeeds easily. Next, she calls on a shorter student to do the same, and he can’t reach. “What does Alex need?” Brazil asks her fourth-grade class. “We can give him a stool, right?”

Tasks that are easy for some kids can be difficult for others, and “not all of you are going to need the same things,” Brazil explains to her students. “But fair doesn’t mean everyone gets the same thing. I want you to stop and think about what you need versus what another classmate might need.”

Talking to students about accommodations can stretch many educators beyond their areas of expertise, requiring them to navigate sensitive conversations about disability while avoiding disclosing private information, especially when kids are unaware of a diagnosis. “I wish I knew the right thing to say,” wrote Dallas-based elementary science teacher Amy Banks when we asked teachers where they need guidance for supporting students with learning disabilities. “I don’t know what to say to my students when they ask things like ‘Why do I have copies of the notes in my folder?’ or ‘Why do I need to listen to the test questions being read aloud?’”

The ability to frame accommodations in a positive way—both for the children who need them and for classmates who are curious or even judgmental about learning supports—is a critical part of creating a classroom where kids respect each other and advocate for their own needs. When teachers avoid the topic entirely or gloss over it quickly, says Rachel Lambert, a disability researcher at the University of California, Santa Barbara, “kids will make meaning of it on their own.” Students with disabilities who feel stigmatized at school, she says, may struggle as adults to “construct a positive identity around their disability.”

We interviewed veteran educators to gather their best tips for discussing learning accommodations with students across the grade levels.

ELEMENTARY SCHOOL: BUILDING CULTURE AND RELATIONSHIPS

The idea of treating a broken bone with a Band-Aid is obviously ridiculous and hilarious to Jeremiah Kim’s fourth- and fifth-grade students, but “I have to be fair,” says Kim, making a show of putting a Band-Aid on a student’s clearly unbroken leg.

This is Kim’s Band-Aid lesson, and after a quick discussion about fairness, he asks several students to act out different physical injuries—a bleeding nose and a broken arm, for example. “I gave Audrey a Band-Aid, so I’m going to have to give you a Band-Aid too,” he adds, as giggles ripple through the classroom.

By treating each student with the same remedy, Kim is making a point about learning accommodations. “I was treating everyone exactly the same… is that helpful?” he asks. “Throughout the school year, you’re going to notice that some students might be treated a little differently than you. Some students work with teachers that you don’t; some students even get rewards that you don’t. When you see that, I want you to remember this activity.”

For Kim and Brazil, conversations about accommodations track throughout the school year. Brazil keeps an anchor chart on her wall reminding students to ask key questions: What do I not know about this situation? Does someone need something that I don’t? Kim regularly references the Band-Aid lesson. “I have students who complain about not getting a reward, and I’ll say, ‘That’s not your Band-Aid.’” Beyond setting classroom culture, the Band-Aid metaphor—though Kim does acknowledge that it can be problematic to equate physical injury with disability—gives kids “language they can use to communicate with me about their needs.”

Kids will be curious: When questions about accommodations come up in class, some teachers reflexively protect students’ privacy, hoping to shield them from potentially uncomfortable conversations. “That’s his plan. Thank you for being on your plan,” said a teacher in a sub-Reddit thread, describing his typical classroom response.

Responding this way, while understandable, can inadvertently signal that there’s something wrong with students who have accommodations that shouldn’t be discussed, cautions Amanda Morin, an educator and coauthor of the book Neurodiversity-Affirming Schools: Transforming Practices So All Students Feel Accepted & Supported. Instead, says Morin, when students ask about a peer’s accommodation, turn it around and ask if they might need support themselves. “That could sound like ‘Tell me why you think you need this accommodation and what can we do to make things work for you,’” Morin says.

Drawing on the familiar helps. When her fourth graders ask about accommodations, Brazil often references eyeglasses. “Everybody needs different tools to be successful,” she tells students. And Morin tells students, “I have a really hard time with planning, so I use the calendar on my phone.”

Know your students: To set kids up for success, find time to discuss accommodations in private, but without sharing a diagnosis—at the elementary level, some may not be aware of their learning disability, individualized education program (IEP), or 504 plan. “Talk about why you’re providing this and ask if there’s something that would work better,” Morin suggests. “Ask if they need it at all times. And I would advise teachers not to force the accommodation if a student is fine without it. Say instead, ‘If you need this, it’s there for you.’”

Before students use an accommodation for the first time, consider explaining how it works. Some of Banks’s students, for instance, use an app to listen to test questions. After a quick demo, she tells them, “You have an opportunity you can use or not. I’m giving a science test, but I’m not testing reading. So let’s take the reading part out.”

These conversations land best when you know your students—Brazil waits a few weeks into the school year before teaching her fairness lesson. “I want to be sure the kids are comfortable with each other and me,” she notes. Kim surveys his students at the beginning of the year to ask about their preferences. “There’s a lot of shame around diagnoses. And so I had to learn the hard way that it isn’t a conversation every student wants to have,” he admits. “It comes down to knowing your students and their needs.”

MIDDLE SCHOOL: GROWING COLLABORATION AND METACOGNITION

Middle school is an important time for students to learn how to advocate for themselves and become more involved in their accommodations, says former middle school English teacher Cathleen Beachboard. “In sixth grade, students might know they have accommodations but don’t know why,” she says. “By eighth grade, I recommend they sit in on IEP meetings and be allowed to ask questions.”

To lay the groundwork for this step, start by gathering basic intel, says Rachel Fuhrman, a former middle school math and special education teacher. “It’s helpful to ask them what they find hard. Sometimes you have to lead them a little bit and ask, ‘Do you feel like you’re running out of time on tests? Are you distracted by other students? Do you need a break to go for a walk?’” Ask students to identify their strengths and weaknesses, says Lambert, the disability researcher. As a middle school math and special education teacher, she’d say, “Some things are harder for you; let’s list them. Some things are easier for you; let’s list them,” she says. At this age, “building their metacognition is the most important thing.”

Help kids get comfortable: For middle school students, who interact with many teachers during the day, part of self-advocacy is getting comfortable reminding teachers about their accommodations. “I’d say, ‘Hey, when you go to science class and I’m not there, you can ask for these things. Every teacher has a lot of students, and they may forget for a second that you need a read-aloud or a scribe,’” says Fuhrman.

Because middle school students are undergoing cognitive changes that make identity and social connections all-important, Fuhrman says, they might need help managing self-consciousness about their learning differences. “Some of my students were embarrassed about their accommodations—like using a calculator when other kids didn’t for math testing.” A quick private conversation with a student can help. “I would say, ‘You deserve to have this. We don’t want you to waste time futzing with calculating when we know you can do the bigger conceptual work.’”

Meanwhile, because students’ needs can evolve as the school year progresses, teachers told us they recommend checking in from time to time to see how accommodations are working and discuss changes.

Use a storytelling lens: Read alouds, though less common in middle school, can expose students to new ideas and help them develop an understanding of others, says middle school English teacher Kasey Short. Some teachers told us they use reading to lay the groundwork for class discussions about disability. One of Lambert’s colleagues created a reading-based activity with sixth graders during which the class read Freak the Mighty and discussed the characters’ strengths and weaknesses.

Beachboard also recommends reading biographies of famous people with disabilities, like Greta Thunberg and Muhammad Ali. “That allows kids to see that these people have taken a variety of paths to complete their education,” she says. “Then it’s not the teacher telling them this, but the stories of other people. That’s important for middle school students.”

HIGH SCHOOL: BUILDING ADVOCACY SKILLS FOR THE REAL WORLD

In high school, students can and should attend their IEP meetings and start making decisions about accommodations, an important step in preparing for young adulthood. “The goal is for them to speak up when they need something different,” says Morin. “At some point we can’t advocate for them, legally. When they become adults, they have to advocate for themselves.”

The tone of these conversations should be “empowering and encouraging independence,” says Beachboard, who currently teaches high school English. “Every high school kid should have a chance to run their IEP meeting by 12th grade. They need to be comfortable presenting to other people and knowing what they need.”

High school is also an opportunity to begin preparing students for what’s next. “I talk to them about how accommodations might look in college or the workplace,” says Donna Phillips, a special education teacher at a Nevada high school. “I always emphasize that asking for support is a strength, not a weakness.”

Teach kids how to prep: By age 16, under the Individuals with Disabilities Education Act, students must be involved in planning for their post-high school transition. “I do think that gives more structure to these conversations,” says Jordan Lukins, a former special educator who trains preservice teachers. “We have to start talking about their goals and preparing them for the fact that they don’t get an IEP in the real world.”

Helping students prepare for IEP meetings is part of that. Lukins suggests giving students a graphic organizer where they can write out what they’re good at, what they like at school, where they want to improve, and questions they want to ask in the meeting. Ask students to look at their grades and suggest changes to their accommodations, Beachboard suggests. This work can be ongoing, notes Daniel Vollrath, a special education teacher at a New Jersey high school. His students keep weekly journals where they “track their progress over time and talk about their achievements,” he says.

Check in: Finding one-on-one time for conversations isn’t easy in high school; Vollrath tries to catch kids in class, but he’s careful to avoid singling them out. “I’ll say to the class, ‘I’ll come around quickly and check in with you all to make sure everyone is doing all right.’ Then I’ll sit next to their desk and talk to them. And then usually I’ll walk around and talk to a few other students.”

During these check-ins, he’ll ask, “How do you feel about your accommodations?” and “Is anything bothersome about how your teacher is following the accommodations?” To ensure that students understand an accommodation, he might say, “OK, draw out this accommodation and tell me a story about it.”

Consider gathering information up front, says former high school English teacher Tarn Wilson, who asked students to fill out note cards with information about themselves, including their accommodations, in the first weeks of school. Then she followed up privately with students. “I’d say, ‘I want to be a good teacher for you. I’m curious to learn more about how you learn. What helps you?’ Many won’t know, but they appreciate the conversation and know that your door is open.”

Be flexible and build autonomy: A number of educators told us that as students mature, they try to offer more flexibility, giving students a say in how their accommodations are implemented in class, for example. If Wilson noticed that students weren’t using a particular support, she’d check in, saying, “I notice you’re not using your accommodation—that’s great. And if that ever changes, we can follow up on that.”

Because giving students the opportunity to make decisions in their learning builds buy-in and motivation, Beachboard offers all her high school English students a range of options on most assignments—a strategy that also prevents kids with accommodations from feeling singled out. “I say, ‘Hey, guys, on this next assignment some of you might want to listen, and some of you might want to read aloud in small groups, or you can read by yourself,’” she says. “Make it a normalized thing for the whole class.” In Vollrath’s class, he’ll often extend accommodations to the whole class, because “depending on the support, it can help everyone,” he says. “I’m a very flexible teacher, and I’ve found that to be very helpful.”