How to Incorporate ‘Spaced Learning’ Into Your Lesson Plans

This powerful, evidence-based strategy works across subjects and grade levels—but you have to plan for it.

Your content has been saved!

Go to My Saved Content.Curricula are usually structured to deliver content to students in sequential blocks—one concept follows another, and often, previously learned material doesn’t resurface until larger assessments at the conclusion of a term.

While this approach might be successful for an immediate understanding of content, research suggests that when students don’t intentionally practice recalling and building on recently-learned material over a longer period of time, they often lose that information just as quickly as they learn it.

“Students might learn these skills in the short term, but they often don’t transfer this knowledge to their long-term memory,” Sara Delano Moore, a former middle school teacher and education consultant, writes in SmartBrief. “Our brains need time to practice the information and to consolidate learning.”

To stimulate long-term retention of knowledge, an authoritative review of research spanning hundreds of studies points to the effectiveness of spaced learning, teaching new material in small chunks spread out over time, and frequently revisiting the material after it’s taught.

A 2021 study, for example, found significantly improved retention in seventh-grade students who solved 12 math problems spread out across three weeks, when compared with students who solved the same number of problems in a single day. When both groups took the same test one month later, the students who used spaced practice scored 21 percentage points higher.

How frequently should recently-learned material be revisited—and how should teachers do it?

In SmartBrief, Delano Moore says that simple moves, like including several problems from one day’s lesson, a few problems from the prior week’s work, and two to three problems from topics introduced a month ago, can make a difference. Meanwhile, cognitive psychology researcher Shana Carpenter argues there’s no universal schedule. She suggests planning gaps that span days, weeks and months—with more time between sessions when material is already familiar to students, and less time when students are first learning new information.

If you want to use spaced practice in your classroom, here are some strategies to try.

A Holistic Approach

Bill Hinkley, a high school math teacher in Maine, recommends thinking holistically about your curriculum at the start of the year so you can determine how a spaced learning approach can be integrated.

The first step, he writes for Ed Surge, is to identify the foundational material in your curriculum, and instead of teaching it during specific blocks, break it up into smaller chunks that can be taught—and resurfaced—on a spaced out timeline.

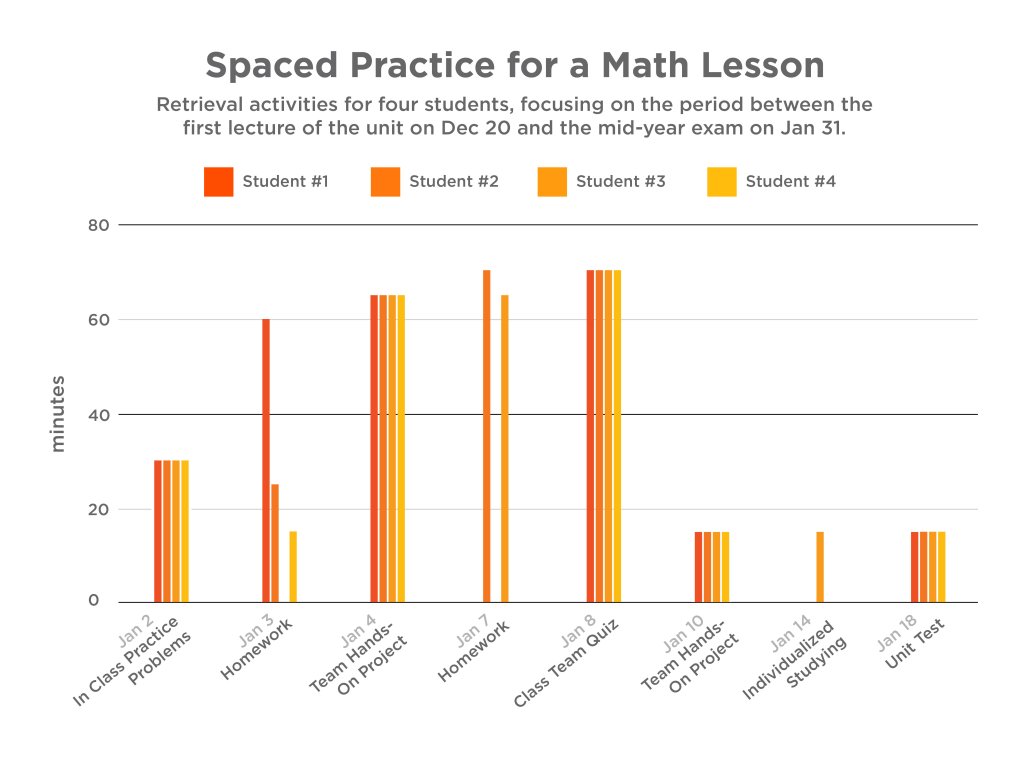

To do this, Hinkley created a chart to visually illustrate his approach to spaced practice for one unit of material in his AP Calculus class. After kicking off with a lecture on the material right before winter break, Hinkley assigned in-class practice, homework, quizzes, and a team project, two weeks later, after break. A unit test followed a week later, and he also included more practice with the material in a mid-year exam.

It’s also important to have students engage with material in a variety of learning modalities, according to Hinkley. For instance, he assigned a hands-on project to encourage both in-class and independent work, and replaced his usual mid-unit quiz with a group review exercise designed to be more memorable for students.

When planning out your curriculum, Hinkley recommends trying to answer key questions like:

- Which skills from previous units can I integrate into my next unit?

- How can I space out the learning in this unit to combat the compartmentalization often inherent to curriculums?

- How can I create opportunities for students to think about previously learned topics outside of the classroom and during homework time?

Spaced Quizzes

Quizzes, especially low-stakes ones, are not just a tool for quick assessment—they can also be a powerful way to implement spaced learning, write psychology researchers and co-founders of the Learning Scientists project Yana Weinstein and Megan A. Smith. “[T]aking a quiz (or doing any activity that forces you to bring information to mind from memory) actually causes learning,” the authors note.

The “power of low-stakes practice tests” is further confirmed in 2022 by researchers John Dunlosky and Shana Carpenter, who found that asking students to review previously learned material through activities like quizzes can “generate memory improvements that persist for 9 months,” while the positive effects of retrieval “over multiple sessions can last for at least 8 years.”

Testing can take the form of ungraded multiple choice, free-recall, or short-answer quizzes—the idea is to create easy, low-stakes ways to prompt students to recall and apply concepts they’ve already learned.

Former middle school history teacher Patrice Bain writes that mini-quizzes that included a mix of new and old material helped increase her students’ retention so much that she replaced homework assignments with them. The key, she said, was to keep them truly low-stakes—she rarely graded the quizzes, and if she did they were worth very few points. “I put them on two-inch by three-inch pieces of paper. They’re very non-threatening. Five quick questions,” told the Cult of Pedagogy podcast.

If you do plan to grade quizzes, Weinstein and Smith suggest having students take them on free self-scoring apps, like Socrative, Memrise, or Google Forms that can provide you with an immediate snapshot of where your students stand.

Spaced In-Class Review

In-class review works hand-in-hand with low-stakes quizzing to prompt students to recall and apply older material over time. For example, Bain often incorporated “blasts from the past” into her new lectures, in addition to her daily mini-quizzes. “When I was talking about, for example, Ancient Egypt, I could say, ‘Oh, remember when we talked about Mesopotamia? What, what was important about that river?’” she told Cult of Pedagogy.

Having students explain material to themselves or peers also can be an effective form of review. Weinstein and Smith suggest having students write a summary of the key points from last week’s class as a quick in-class activity. To build in more complexity, students can check their notes and revise their key points. It’s important that students eventually write these summaries in their own words—from memory, if possible—which increases retrieval and results in stronger retention.

Similarly, you can try starting your class by pairing students for 90 seconds of rapid review: Have them summarize what they learned in the prior class, then present to the larger group—or use think-pair-share activities to get students processing key facts and ideas from a topic previously covered in class, then pair up to compare notes and look for gaps in their learning.

Cognitive scientist Pooja Agarwal, who joined Bain on The Cult of Pedagogy to discuss the book they co-authored, warns teachers to be prepared for discomfort when students struggle to remember material and feel frustrated during this process. That’s a sign your spaced approach is working: “Students are going to forget,” she says. “But it’s important for students to forget. Because with spacing, they bring it back up, and that then solidifies that learning moving forward.”

A Spaced Approach to Studying

Teaching students how to incorporate spaced learning into their study routines at home can help them take advantage of its benefits themselves.

Chicago-based educator and neuroscientist Edward Kang suggests introducing students to a specific approach to working with flashcards that uses spacing to structure retrieval practice. “The cards they’re able to answer immediately should be placed in a pile to review three days later; those answered with some difficulty should be reviewed two days later; and those that they answered incorrectly should be reviewed the next day,” he writes.

To help students integrate spaced learning into their study habits, AP psychology teacher Blake Harvard uses a class activity to show its effectiveness. First he creates a content-specific chart to help students organize information about a concept, for example, Piaget’s Theory of Cognitive Development.

Students fill in the chart using what they remember from prior class work—without using their notes—and highlight those answers in yellow. Next, they use their notes to correct the chart, highlighting those additions in orange. Finally, they ask peers and skim textbooks to fill in any remaining blanks, highlighting that in blue.

A few days later, Harvard distributes new, blank charts, and the students follow the same process. A week later, he repeats the activity again and has students review all their charts and pull out insights. “Most will see an increase in yellow highlighting, indicating they’ve remembered more information from day to day, or from retrieval to retrieval,” he writes.

To emphasize the usefulness of this strategy—and motivate students to make use of it on their own—Harvard asks students to discuss questions like: “Did this take more time than cramming?” and “Was it more effective at showing you what you know and don’t know?”