Portrait of a Turnaround Principal

What does it take to turn a low-performing school around? A principal finds success by focusing on both love and high expectations.

Your content has been saved!

Go to My Saved Content.The rest of her wardrobe is no-nonsense, but Principal Sonya Mora usually wears high heels. If she doesn’t, some of the fifth graders at Samuel Houston Gates Elementary in San Antonio tower over her. But not even her five-inch pumps slow her down as she beats a brisk path between classrooms, where she’s constantly observing, modeling instruction, and offering one-on-one support for students at risk of falling behind.

Mora gives plenty of hugs. She’s not cuddly, but she exudes a durable affection that her students need, greeting them as they come in every morning and often telling them she loves them because she knows they need to hear it—these students live with high rates of toxic stress, trauma, and chronic poverty.

Mora embodies a point that Pedro Martinez, San Antonio Independent School District’s superintendent, made when he came to the district in 2015, the year Mora took over at Gates. When he began talking about a culture of college-level expectations, some pushed back, saying that for kids with the issues facing the district’s students, the primary need wasn’t ambition but love.

“Absolutely, let’s love them,” Martinez said, “but let’s love them all the way to Harvard.”

In four years of Mora’s leadership, Gates has gone from being one of the lowest performing schools in the state of Texas to earning an A in 2018. Her methods, she says, are not revolutionary or novel: Being “all about the kids” and “data-driven,” and focusing on curriculum and instruction, aren’t buzzy new things. But they’re working for Mora, who is relying on master teachers to bring students up to grade level and beyond. These master teachers work closely with their fellow teachers and campus administrators, and together they all pay close attention to granular, weekly data tracking student progress.

Students With Acute and Long-Term Trauma

Mora’s work is complicated by the highly mobile population she serves. About half of the students at Gates walk to school through a drug corridor known as The Hill. The rest are living in the old, often dilapidated homes surrounding the school, often with their grandparents or other extended family members. They bounce back and forth to parents who may or may not live nearby. Some don’t have homes at all.

Poverty is endemic: This year Gates has 212 students, only six of whom don’t meet federal criteria to be counted as “economically disadvantaged.”

“You do feel bad for the kids, but what we all know is that in order for them to get out of this cycle of poverty, they have to have an education and they have to think critically,” Mora says. “They have to be able to advocate for themselves.”

The conditions she found when she arrived at Gates four years ago—low morale, low expectations, kids spending a lot of time out of class for disciplinary reasons—made Mora feel as though society had already written off most of her students, 97 percent of whom are black or Hispanic. Their backgrounds and discipline records seemed to point to a continuing cycle—a cycle Mora has been determined to break.

The View From the ‘War Room’

Mora has a master’s degree in curriculum and instruction, and she wants teachers to deliver the highest quality content available in whatever instructional context necessary—small group, one-on-one, whatever the students need.

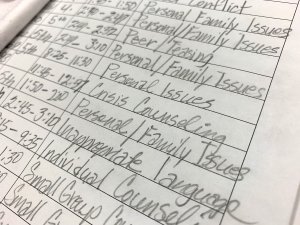

Making that work, for Mora, is all about the details—details she tracks in a converted classroom she calls her “war room.” The walls are covered in data that is scribbled, graphed, and color coded to show how students are performing week by week.

The numbers on the walls have changed considerably during Mora’s four years at Gates. When she arrived in the fall of 2015, it was the lowest performing school in San Antonio ISD, among the bottom 4 percent of schools in Texas, and at risk of closure by the Texas Education Agency. The campus has improved every year since, and after state assessments in spring 2018, Gates earned an A, making it the most dramatic turnaround campus in the city. Overall performance on the state assessments went from 39 to 77.

Texas also gives a rating for “closing performance gaps” between high- and low-performing ethnic groups. In 2015, Gates earned a 20. In 2018, it earned a 100.

Enrollment has dropped as the East Side of San Antonio has been flooded with charter schools; San Antonio ISD has opened some choice schools as well. Gates’s reputation has been hard to overcome, Mora says in explaining the falling enrollment. Parents assume they’ll be better served elsewhere even though Gates is, Mora says, “the only A school on the East Side.”

A Boost From the District

In 2016, San Antonio ISD won a $46 million federal Teacher Incentive Fund grant to place master teachers across its highest-need campuses. Gates has eight master teachers—half the teaching staff—including some teachers who were already there and were promoted. They’re paid more by the district—up to $15,000 more per year—and at Gates they teach an extra 45 minutes per day.

The year Mora started, more than a quarter of the teachers left the school, on par with turnover from previous years—Gates was a tough place to work. Some were not replaced because of declining enrollment, so at the start of Mora’s first year, 15 percent of the teachers, including some of the master teachers, were new to Gates. But since then, the campus has not hired a single new teacher—Mora’s teachers are staying. The only losses have been due to declining enrollment and internal promotions.

In the Work Together

All administrators at Gates participate in the teachers’ professional learning communities, and work with teachers on lesson planning, strategizing interventions for struggling students, and coming up with ideas on how to challenge students who are already excelling.

Mora regularly visits classrooms to teach a lesson, demonstrating the kinds of strategies she wants teachers to try. She also sits with teachers to review student data and get feedback on the interventions they’ve tried. Teachers say she keeps track of the reading, math, and classroom management issues they’re facing, as well as the ways they’ve tried to solve those issues. Because of that tracking and the close communication, Mora never suggests something that teachers have already tried or something that doesn’t make sense for a particular student—suggestions that can feel condescending, her teachers say.

In disciplinary situations, the teachers know that Mora prefers that they do what they can to keep kids in class—when Mora arrived, disciplinary exclusions were bogging down instruction. Kids just weren’t in class as much as they needed to be, she says: “You can only punish so much and so long.”

Mora was prepared for an argument with her teachers on this issue, she says, as there are educators throughout the country who oppose the approach out of a belief that it creates chaos for the other students. But as instruction improved and kids began to be engaged and challenged in class, she saw discipline numbers go down in tandem.

First-grade master teacher Veronica Saenz, who has been at Gates for 13 years, appreciates Mora’s approach. The only data that really mattered to previous administrators, she says, were the standardized test numbers. They’d look at end-of-year data and respond, but it was too little, too late.

Saenz says that Mora intervenes frequently throughout the year, never letting things get too far off-track before stepping in to help. Seeing her commitment to student progress, even in the grades that don’t take state tests, “builds trust,” Saenz says.

Next Steps

This year the campus received a $1 million innovation grant from the Texas Education Agency, administered through the district, for tech upgrades and flexible seating, but Mora places more weight on another strategic move: Gates is set to become an in-district charter.

San Antonio ISD allows campuses that can muster buy-in from 67 percent of teachers and parents to apply for an internal charter, which gives a school freedom to modify the curriculum in an attempt to better serve students. Mora has more than the support she needs to adopt balanced literacy, guided math, and blended learning curricula that differ from the district’s. The charter, she feels, will keep Gates’s progress from stalling.

“Even though we’re highly successful,” Mora says, “we still know we have room to grow.”

She’d like to see writing and reading scores rise out of the 60s and 70s on state assessments. Part of her A rating came from the speed of Gates’s improvement on those assessments. In states like Texas, where growth measurements have become part of the rating system, it can be difficult to keep up the pace.

The culture inside Gates has changed radically, but outside the doors of the school, things are just as tough as they were four years ago. The neighborhood is not gentrifying like other parts of the district. The housing stock is small and cheaply built—it was never intended to attract the middle class. The neighborhood always has been, and likely will remain, a low-income area where kids face the challenges of poverty. As such, Mora says, the work of teaching at Gates will always be to provide tools to meet those challenges.

“We don’t complain about it,” Mora says. “We just make it work, because we don’t have a choice but to make it work.”