7 Projects Teachers Stand By

Planning for projects can be difficult and time-consuming. This list of teacher-tested projects—complete with printable resources—should offer a big head start.

Your content has been saved!

Go to My Saved Content.Many teachers acknowledge the benefits of project-based learning, but they may struggle to think of project ideas that could easily slot into their preexisting units. Perhaps even more commonly, teachers may simply lack the time to conceptualize and plan out projects to run in class.

To help those educators, we’ve compiled this list of seven projects, spanning elementary grades through high school, and from science to English. Many of these projects come directly from educators in our community who left comments on our social feed; we followed up via phone and email to gather more detail.

Though the projects range in length from five days to an entire quarter, we’ve prioritized projects that are relatively easy to plan and implement. We’ve also selected projects that are rigorous, yet creative—getting students to reckon with standards-aligned content in engaging or surprising ways. When possible, we’ve embedded the handouts, rubrics, and resources these educators use to run their projects—as well as samples of completed student work—to make each project as easy as possible to understand and to replicate.

Whodunit: A Murder Mystery Project

At their public Pennsylvania high school, Megan Heefner and Jenna Reich spice up their 11th- and 12th-grade English elective class with a trimester-long murder mystery project that serves as the guiding structure of the course.

Over the time of the unit, students read the mystery novel Reconstructing Amelia, by Kimberly McCreight; the aim is to help students hone their skills of literary analysis via close reading, character analysis, and deductive reasoning as they try to identify the killer. Students submit key work products at three “checkpoints” spaced throughout the unit. One recurring step is the Detective’s Log, a weekly worksheet that students fill in with notes as they progress through the novel. Students also complete witness statements, which put them in the shoes of a character who interacted with the victim prior to the murder; person of interest profiles, which lay out the motives and alibis of characters who might be the murderer; and medical examiner reports, which detail the known facts about the victim’s injuries and cause of death. (For each of these resources, we’ve linked to a blank worksheet created by Heefner and Reich that teachers can copy and reuse.)

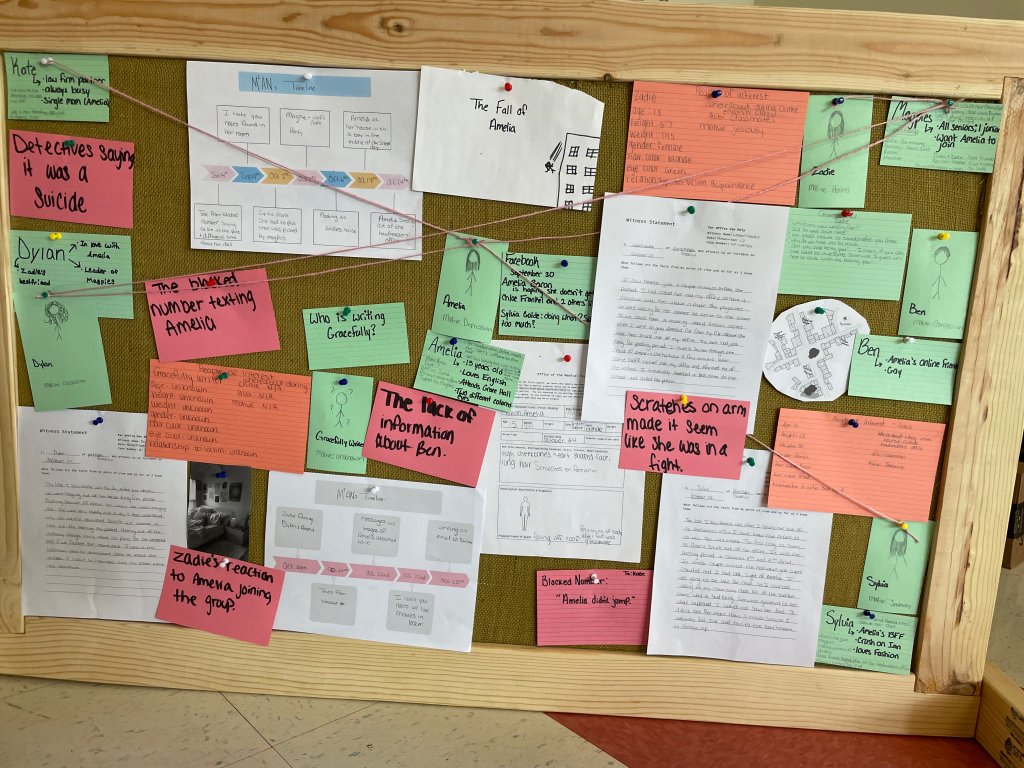

In small groups, students use the resources they’ve filled out to compile key facts onto an evidence board—much like you’d see in a police show, complete with red string linking related details together. When making their evidence boards, students can tap into their strengths: Some groups choose to focus on elucidating their thoughts through written flash cards, while others take the opportunity to put their art skills on display. Groups update their evidence boards throughout the course; the finished product is due at the end of the unit.

To keep students on track, here are checklists of all the elements Heefner and Reich expect them to have completed by Checkpoint 1, Checkpoint 2, and Checkpoint 3—each spread three weeks apart.

Heefner and Reich have aligned the project with standards like “CC.1.3.11–12.D Evaluate how an author’s point of view or purpose shapes the content and style of a text” and “C.1.5.11–12.A Initiate and participate effectively in a range of collaborative discussions on grade-level topics, texts, and issues, building on others’ ideas and expressing their own clearly and persuasively.”

A Fishy Test

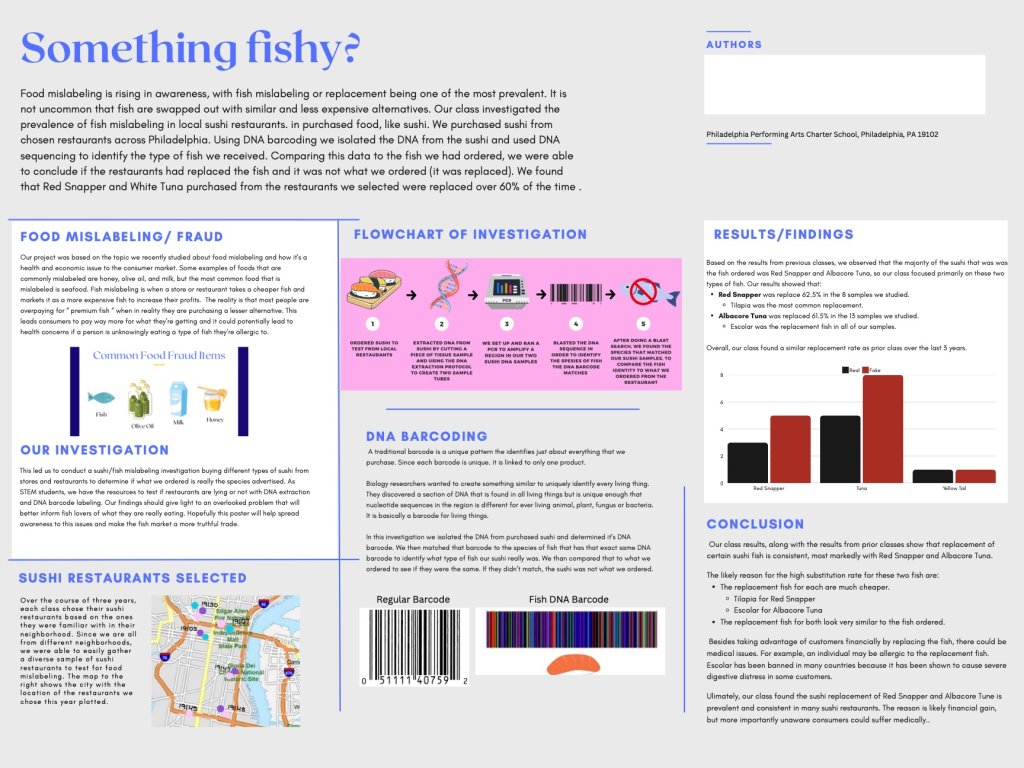

Is the tuna in your sushi actually tuna? It may not be—as Sheri Hanna’s 12th-grade biology students find out during a two-and-a-half-week investigation she runs each year at her Philadelphia charter school.

As part of a broader unit on DNA, Hanna’s students learn about how food mislabeling is a pervasive issue. Then—to bring the subject close to home—Hanna has students vote for about eight different local restaurants that sell sushi; you could also buy fish from a grocery store. From these, Hanna chooses six and buys samples of fish from each. Students then apply their knowledge of DNA and DNA testing to test whether each fish sample matches the species it’s being sold as. In early years, Hanna partnered with a local biotech start-up to provide small groups of students with a portable thermocycler needed for this DNA analysis—but she has also identified a number of inexpensive online suppliers for the relevant DNA testing materials (from thermal cyclers to microcentrifuges), listed here.

Hanna has done this project since 2017, and each year her students discover that a sizable portion of fish—often around half—is mislabeled; tuna is frequently swapped out for escolar, and red snapper for tilapia. Many of her students are full of righteous indignation by the end of the project, Hanna says, demanding to confront the restaurants—or even sue. But Hanna chooses not to tell her students which fish came from which restaurant and reminds them that the mislabeling may be the fault of the wholesale supplier, not the restaurant itself.

After the investigation, the class collectively makes a poster describing the process and their findings; small groups of students are responsible for one small piece of the poster, like the “Results” or “Conclusion” section. The poster gets hung in the hallway for the whole school to see. Students are also graded on their individual lab notebooks.

Hanna designed this unit to give her students a deeper understanding of DNA, while also offering them hands-on experience with some of the scientific tools used by actual biologists. To see this project in action from one of the very first years Hanna ran it, watch Edutopia’s 2018 video here.

Stop-Motion Videos

At Victoria Crossan’s Ontario elementary school, groups of fourth- to sixth-grade students spend a few afternoons a week, over the course of about six weeks, creating their own stop-motion videos.

This project isn’t tied to a particular subject area, so students have free range to choose a topic for their videos; the only requirements are that it tells a story or teaches the viewer a lesson, Crossan says. In small groups, students brainstorm a variety of video topics, then present them to the entire class for feedback. Once Crossan has helped her students settle on a topic, she also gives them free range to choose the medium for their videos. For example, one group used Lego, clay, and painted cardboard sets to make a two-minute video called Planet Trash about the perils of pollution. Another group focused primarily on clay to tell a one-minute story called Dark Secret at the Ice Cream Shop.

Creating even a single minute of stop-motion footage is a very involved process, Crossan says. Students have to decide on their video idea, write a script, then begin to design the props and backgrounds they’ll need for the short film. After that, moving and photographing the relevant characters and props takes several hours. Finally, students have to record voice-over, choose music and sound effects, and edit it all together. Each step in the process was largely self-paced, but Crossan checked in with each group regularly to make sure they were on schedule.

Crossan links the project to specific Ontario standards, such as “Apply the creative process to process drama and the development of drama works, using the elements and conventions of drama to communicate feelings, ideas, and multiple perspectives” and “Plan, develop ideas, gather information, and organize content for creating texts of various forms, including digital and media texts, on a variety of topics.”

A subject-area teacher interested in harnessing the power of stop-motion could condense this into a shorter unit and require that students choose a video topic related to something they learned in class. For more details on the process, which includes phases like “brainstorming and storyboarding,” “set, prop, and character design,” “filming,” and “voice-overs and sound effects,” see this article that Crossan wrote; many of the students’ completed videos can be found on YouTube here.

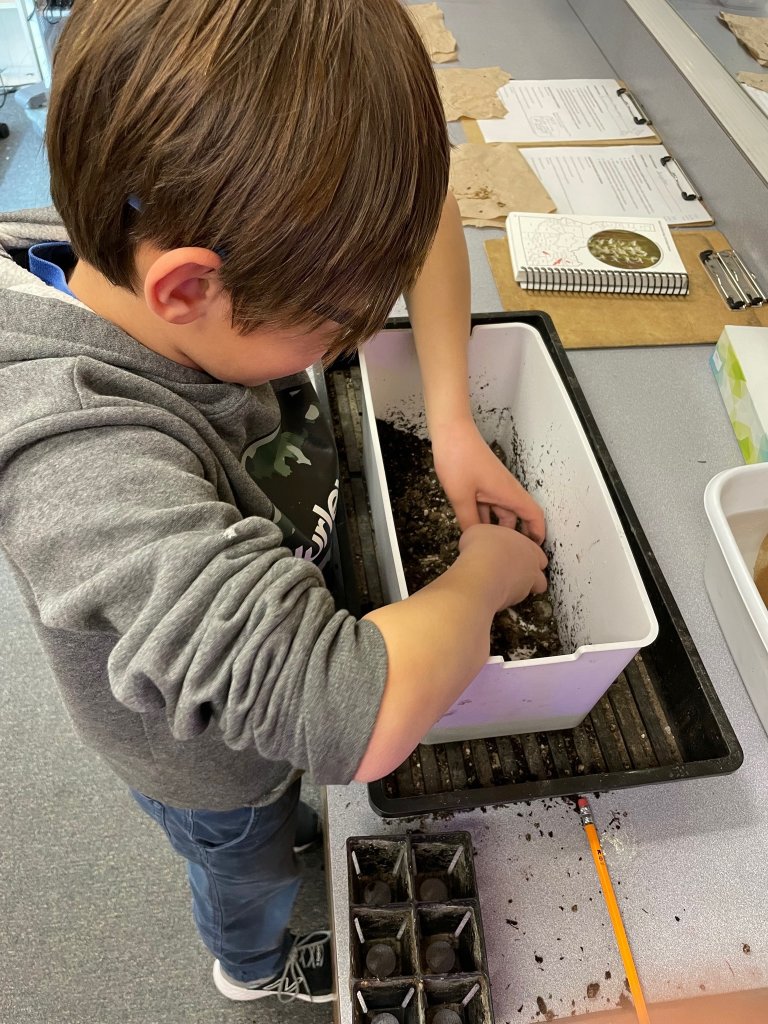

A Learning Garden

After researching the benefits of access to the outdoors—spurred in part by frustration that their own class lacked a window—fourth-grade students in Tricia Galer’s class persuaded their Idaho school board to let them create a small garden at their school made up of native plants selected for their ability to attract pollinators like bees and butterflies.

Galer directed her students throughout the entire multiweek process. To begin, they researched the effects that nature can have on learning and the brain; then they wrote persuasive, evidence-backed statements to deliver in front of their school board. (Here is the master script the students ended up creating.) Once they had received approval to create a small garden on school grounds, Galer’s students went back and did deeper research into the design: What materials would they need? What species would they plant? What would those plants need to survive?

During the process, Galer invited local horticulturalists, biologists, conservationists, and gardeners to come speak with students. Ultimately, the class decided to focus on selection of native plants and created a thorough spreadsheet to weigh their options and determine which flora would make the final cut. A few students were responsible for marketing and fundraising—calling local businesses to ask for donations in the form of cash or supplies. All in all, Galer estimates that the garden cost about $1,200, with roughly $500 coming from fundraising, $500 from a grant from the Idaho Environmental Education Association, and a few hundred more coming in the form of soil and plant donations from local businesses.

The final step: With a little help from gardeners and volunteers, the class constructed the garden. During the school year, various classes might use the garden to learn about botany or biology, or simply help to keep the garden in good shape. “In the summer we partner with our local county extension and volunteers looking to complete their master gardener certificate,” Galer says.

Galer says the project taught her students a lot about biology; it integrated science standards like “4-LS1-1. Construct an argument that plants and animals have internal and external structures that function to support survival, growth, behavior, and reproduction” and “4.SS.2.1.1 Use geographic skills to collect, analyze, interpret, and communicate data.” Meanwhile, pitching and fundraising honed students’ persuasive writing skills, in alignment with the standard “ELA 2: I can clearly and effectively express my ideas (in written and oral form), for particular purposes and audiences, using diverse formats and settings to inform, persuade, and connect with others.”

Here is the standards-aligned lesson plan that Galer created, and here is a timeline of the project.

designing Dream Houses

To make math more tangible for the third-grade students at her Connecticut public school, teacher Kim Hannan leads a “dream house” project, which Edutopia filmed during a visit last year. For an hour a day over the course of five days, students are broken into small groups of three or four to create their dream houses.

There are clear guidelines: Students must design a floor plan including at least four rooms and comprising at least 900 square feet, before calculating perimeters and surface areas so that they can add flooring and paint. (Some students consider special features, furnishings, and more.) Students must stay within a total budget of $200,000; going over budget requires them to reconsider their decisions. Hannan offers students worksheets to track their flooring and paint calculations.

This project integrates a variety of elementary-level math skills, including areas and perimeters, multiplication and division, and measurement, drawing from standards like “5.NBT.4. Use place value understanding to round decimals to any place” and “5.MD.1. Convert among different-sized standard measurement units within a given measurement system (e.g., convert 5 cm to 0.05 m), and use these conversions in solving multi-step, real-world problems.” Students are also introduced to the lifelong skill of budgeting.

Here is the complete lesson plan that Hannan created for the dream house project, and here is the handout (with accompanying rubric) describing the steps of the project that Hannan gives to her students at the beginning of the lesson.

a Sustainable Fashion Show

At his Colorado high school, science teacher and makerspace coordinator Josh Morris educates students about the fast fashion crisis—and offers them a hands-on look at what individuals can do to combat it. Morris partners with math teacher Michael Rose to lead a five-week project (taking up roughly 10 hours per week) in which students cut and sew together their own clothes using recycled materials, culminating in a fashion show in front of the entire school.

Math is integrated throughout the unit. For example, during the first week, students learn about the economics of the fashion industry (such as labor and materials costs) and how these can result in inexpensive, poor-quality products flooding the market. In later weeks, though, the math becomes very hands-on, Morris says: Students learn about patterns (and design their own), using ratios to determine how a particular design might look when scaled to a different size and calculating how much of each material they’ll need to create their finished clothing.

Once students have a sense of what they want to make, Morris and Rose take the class on a trip to a local thrift shop, where they’re given a budget of $20 to buy old clothes and fabrics to use in their upcycled clothing. (They go when the local store offers “Discount Tuesdays,” Morris says, and every item is on sale for just one dollar.) Then, for the final few weeks, students use sewing machines, embroidery machines, vinyl cutters, and heat presses to turn their designs into a reality; students either add new elements to the recycled clothing items to revitalize them, or create entirely new articles of clothing by cutting the old clothes into pieces and sewing those back together.

This unit gives students great hands-on experience with a variety of useful garment-making tools, Morris notes. Plus, math practice is baked in throughout, aligned to Colorado standards like “HS.G-CO.D. Congruence: Make geometric constructions” and “HS.G-MG.A. Modeling with Geometry: Apply geometric concepts in modeling situations.” The project culminates in a fashion show, during which students present their clothes and describe the materials and methods they used to create them. Here is the lesson plan where Morris and Rose lay out the timeline and requirements of the project.

Bioethical Dilemmas

At her public high school in Maine, ninth-grade biology teacher Jenny Crowley leads a multidisciplinary unit called “Questions of Conscience.” While STEM is at the core of the quarter-long unit—kids learn about genes and genetic modification—it also integrates skills from the humanities, requiring students to grapple with tough ethical questions.

For the first few weeks, students are given lessons in biology that culminate in thoughtful discussions. For instance, during a lesson about sickle cell anemia—which Edutopia recently filmed for a video—students make paper models representing hemoglobin’s shape in people with and without sickle cell to see how the affliction can cause blood clots. At right is the printable paper model Crowley uses—you’ll want to practice a few times to make sure you’re ready to clear up any confusion when the kids try it—and here’s an accompanying worksheet.

Then, students are asked to read a New York Times article about a 12-year-old boy who was the first commercial patient to receive gene therapy to treat sickle cell, and reflect in a short writing exercise about the pros and cons of the expensive experimental treatment. Finally, in small groups, they share their thoughts with one another, using a handout to store their notes.

Other early-unit lessons follow a similar structure, but on different topics—including a debate over whether it’s acceptable to genetically modify a human embryo to produce a more athletic child, and a discussion about the benefits and harms of direct-to-consumer genetics tests that indicate people’s risks of developing particular diseases.

The latter half of the unit is focused more on self-directed research, Crowley says. In a recent iteration, for instance, students could choose from three different research paths: “Should we edit the human genome?” “Should genetic information be public?” and “Should discarded genetic material, like fetal stem cells, be used for science and medicine?” After choosing a topic, students must find relevant sources and submit an evidence-backed paper defending a particular position. As students work on these in the background—with guidance from Crowley—the unit also continues to have standard biology labs and quizzes.

At the end of the unit, students are graded on their position papers, as well as on their participation in a final full-class discussion about the bioethical questions the students researched. Crowley says she designed the unit to help students learn more about biology, but also to help them use the Claims, Evidence, Reasoning (CER) model to effectively present a research-backed argument. She hopes that by the end of the quarter, students have become more thoughtful decision makers and more effective communicators about science.

Help us get to 10!

We’ll be continually updating this article with other compelling projects we come across. We welcome educators to leave their project ideas in the comments. If you do, we may reach out to you for more details so we can add your project to the list!