Ron Berger on the Power of ‘Beautiful Work’

To motivate students and teachers alike, we need to deepen the work of schools and give everyone the time and space to work toward greatness, says the noted educator.

Your content has been saved!

Go to My Saved Content.During the nearly three decades that Ron Berger taught at Shutesbury Elementary School in rural western Massachusetts, there were no textbooks in the small school building. Instead, Berger and his teaching colleagues, with approval from local families, built a curriculum focused on contributing to the community in productive, meaningful ways. “It included craftsmanship and hard work and things that local working class people really got, really valued,” Berger recalls. Rigor and high standards were at the core, he insists, but they existed in service of doing important, exceptional work—he calls it “beautiful work”—that made an impact beyond the classroom.

“My sixth graders tested the water quality of all the local streams and lakes. They tested everyone’s private wells in town to see if their water was safe to drink. We cleaned up the playground and built playground equipment, a recycling shed, and a playhouse for kindergarteners,” says Berger. “We were able to take elementary-age kids and do adult-level scientific and demographic research. They learned how to use computers for this work, they learned Excel, and they prepared reports for the town and for the state.”

When these Shutesbury students headed off to the regional junior high school, “they did well because they loved school,” Berger says. “They hadn’t lost that curiosity and spirit. Already as kids, they felt like they had done important work. And when they took the standardized tests for the state, their test scores were also good.”

It was a remarkable paradigm shift, driven in no small part by the conviction, Berger explains, that “for the rest of your life, you won’t be judged by test scores. You’ll be judged by the kind of human being you are, and the kind of work that you do.”

Convinced that the model was portable and could work in any school environment, including urban high-poverty schools and with or without textbooks, Berger took what he learned in Shutesbury into the next phase of his life: He left the classroom to become chief academic officer for the nonprofit school improvement network EL Education, originally called Expeditionary Learning. “I felt so strongly that more kids deserve an adventurous, challenging world of school where they can actually connect their learning to doing some good for the world. It’s so motivating. So the rest of my life has been spent seeing if I can take that privilege I had and spread it around more broadly to other schools and districts.”

Dialing in over Zoom, Berger, now a senior advisor to EL Education and author of multiple books, including An Ethic of Excellence: Building a Culture of Craftsmanship with Students, spoke with Edutopia about what makes a great teacher, the importance of rethinking the role of students, and the powerful impact of guiding students to create high-quality, meaningful work.

Sarah Gonser: You come off as naturally curious about the world and people—and your educational philosophy seems contingent on nurturing curiosity in children. Is cultivating curiosity something we fail to prioritize in public schools?

Ron Berger: I love that you brought that up as a concern because I think every kid in the world is deeply curious. And if you’re lucky enough to teach pre-kindergarten or kindergarten, which I was—way back when—you get these 4-year-olds and 5-year-olds who are curious about everything. They just can’t wait to learn everything. And somehow by high school, we turn them off.

I don’t blame school entirely for that. Part of it is the arc of our lives and society and kids growing up and maturing. But I do blame school for some of that: We take the adventure and curiosity out of learning for kids in the way we structure schools.

Gonser: How do we take the adventure and curiosity out of learning—what is it about the structure of school that does that, do you think?

Berger: Schools are set up to measure things with test scores. I’m not anti-test, but it’s such a limiting and reductive way to corral people’s energies that you end up having to let go of the conditions that create passion and produce great work.

When I was in school growing up, I’d write a paper and hand it to my teacher. No one else saw it. It came back to me with a grade. I took one look and threw it away. But imagine if the work I did in class was like a play I was acting in, or a basketball team I was on, and every one of the people I care about was going to be looking at my work. I would want to make it beautiful and I’d want to be proud of it.

I’m talking about authentic work with audiences that go beyond the teacher, in a setting where kids have the scaffolding and encouragement to improve: a lot of time for multiple drafts and plenty of expert critique, like in the real world. It sounds revolutionary when you talk about it in school, until you think about what anyone does in their job.

Gonser: Prioritizing a different set of values in school was part of the thinking behind founding EL Education—which at first involved just 10 public schools in the early ’90s and now includes 152 schools across the country—isn’t that right?

Berger: That is true. EL Education started at Harvard Graduate School of Education in a partnership with Outward Bound, the wilderness organization. It was a strange partnership because people think: How can school be connected to wilderness? But the thing about Outward Bound is that it doesn’t take people into the wilderness to build wilderness skills. It takes people into the wilderness to build teamwork and character. They put a group together to get to the top of the mountain; you have to figure out how to depend on people and work together and be a better version of yourself. And it’s hard, and it changes you. And at the end of it, you feel like you’ve become a stronger, more selfless, and less whiny person.

What if school was that way? What if we could build schools full of teamwork and adventure, where we all get to the top of the mountain, instead of competing individually to get to the top first?

Gonser: That’s an exciting idea, but I don’t think everyone agrees that building character belongs in public schools.

Berger: Public schools were not founded in this country to prepare kids for tests. They were founded to prepare them to be good citizens.

We’re talking about being a good human being who stands up for what’s right, who respects all human beings, who stands up against racism, against sexism, against what’s wrong in the world. That has to be part of what education is.

And so EL schools really lean into this idea that character matters and that creating the future leaders and citizens of America can’t just be a Tuesday afternoon citizenship class. It has to be the way school is run all day long because your academic courage, your academic compassion, your academic collaboration that you learn in math class, in history class, in science class—it shapes who you are as a person and influences who you’ll be when you go into the working world.

Gonser: At the center of all this is this idea of beautiful, rigorous work. It’s a particular passion of yours. What does it mean, and why is it important?

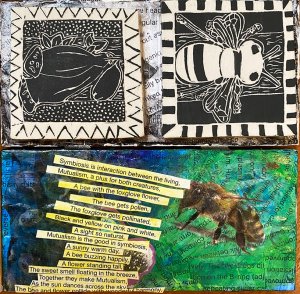

Berger: When I say “beautiful work,” people think aesthetically beautiful work. But I also think scientifically beautiful work, mathematically beautiful work—it can be in any field. Sometimes beautiful work is acts of courage and kindness and contribution to the world. Civic action can be beautiful work, artistic expression can be beautiful work, scientific ideas can be beautiful work.

Gonser: You say it can be a powerful motivator. What do you mean by that?

Berger: It’s not “Just complete this worksheet,” or “Just try to get a good test score,” or “Try to be proficient.” Who gets excited about being proficient?

When you’re proud of your work, when it’s beautiful, you’re motivated to work harder. Kids practice their gymnastics, practice their flute, practice their soccer skills because they want to be great. Not to be proficient.

And I feel like that’s what school should be about. It should be inspiring kids to want to be great, to do beautiful writing, beautiful reading, beautiful mathematics. So when someone posts her mathematical solution on the whiteboard in ninth grade and the other kids are like, “Oh my God, what a solution!”— that’s what I want. And when I see it in schools, I know why I’m in education. Seeing kids do beautiful work and recognize beautiful work in each other.

Gonser: You’re describing a lot more student ownership and the integration of big, challenging projects—that requires really skilled teachers. What do you think makes a great teacher?

Berger: First of all, I think almost everybody goes into teaching with a noble purpose. If you’re choosing teaching, you’re choosing a job that often attracts derogatory comments and is rewarded with low pay. So why do you choose it? It’s because you want to change kids’ lives.

But I think the bureaucracy of schooling—and this is not one person’s fault—distances teachers from their passion. So they get caught up in the day-to-day pressures and lose touch with why they’re there in the first place. Helping teachers improve is about reconnecting them to their hearts.

It’s a mindset of continuous improvement that makes for a great teacher: “I’m going to keep getting better all the time; I’m going to keep improving my work as a teacher.” I think that growth mindset is a trait we can cultivate in teachers or squash in teachers, and I think we often squash it.

Gonser: And how do you cultivate that mindset?

Berger: We need to create environments where teachers are incentivized to show what they’re good at, reveal where they’re struggling, and share their best practices to help everyone teach more effectively. Educators should always be improving—like a soccer team improves, like an orchestra improves. You’re always critiquing; you’re always working together and getting better as a team.

Gonser: That calls for very intentional planning on the part of school leaders, making space for that to happen, putting the structures in place.

Berger: Yes, for sure. Teachers in this country get less collaborative planning time and thinking time than teachers in most other countries. We prioritize time in front of kids. In many other countries, teachers have two or three times as much time to get together with colleagues and say, “I’m struggling teaching this. Here’s the work for my students. What would you suggest?”

We need to build in more teamwork, and we need to have professional learning opportunities where teachers can present their best thinking and their challenges to each other, and examine each other’s work. We need to think of it as a team process.

Gonser: A focus on high-quality work sounds really time-consuming. As schools reopen now, teachers are prioritizing what they need kids to learn this year. There’s pressure to move quickly and cover lots of content. When and why devote precious hours to this kind of work?

Berger: That’s the hardest question because teachers feel the pressure for coverage and I understand that. But if you never go deep and long to produce high-quality work during the school year, kids never understand what they’re capable of doing, and they never develop the passion for the academics that you wish that they would.

So my thought is: Figure out at what points during the year you can go deep and produce something great. If you want kids to care about chemistry or literature or writing—instead of just being obedient or disobedient—you’ve got to take a break periodically and focus on doing something great.