Celluloid Hero: Bringing Cultural Education to Kids

Filmmaker Ronald Chase uses the power and mystery of cinema to prepare teens for their toughest assignment: real life.

Your content has been saved!

Go to My Saved Content.

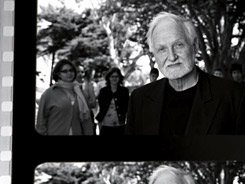

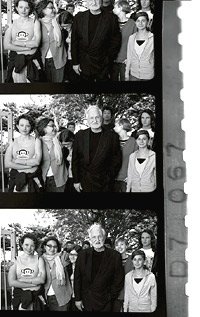

In the theater lobby of San Francisco's legendary Dolby Studios, Ronald Chase has assembled a group of teenagers for an interesting cultural experiment. Under normal circumstances, these adolescents might be engaged in activities typical of their demographic: hanging out in Golden Gate Park, engaging in marathon video game sessions, or cruising a local mall. But Chase, a white-haired painter and filmmaker, has something entirely different in mind: a screening of Federico Fellini's 8 1/2, considered one of the most challenging and sophisticated films of the twentieth century.

Given the supposed attention span of today's youth (short) and their presumed tolerance for challenging work (low), you might think the turnout would be sparse. But the room is packed. Nearly a hundred teenagers form a diverse racial and social group. Some are Asian, some are Middle Eastern; some travel in chattering packs, others are solo. As I sink into a plush seat in the elegant private movie theater, I hear a young voice behind me: "Did you catch Noises Off when it was in town? Very, very cool." Welcome to the world of Art & Film for Teenagers, a free weekly gathering for Bay Area students that is doing its high-level best to introduce them to classic elements of modern culture.

"OK, everyone, let's get started," Chase says, clapping his hands twice as he directs stragglers to their seats. What follows is a mini-lecture on Fellini delivered with the self-assured touch of a man who knows both his material -- "The title comes from the fact that Fellini had made seven and a half films before this one" -- and his audience: "Quite frankly, this is going to be a bit mind blurring for you," he tells the group, which also includes some adults. "But you should know that 8 1/2 has turned more people into filmmakers than anything else. Let's learn a new word to help us. You can throw it around with your friends when you want to appear intellectual. The word is nonlinear." As the lights dim, Chase offers one last piece of advice: "If you get lost, just hold on; it goes by very fast, and you won't be there for long."

Chase, who started the program thirteen years ago, says his feeling was, and remains, that though teachers might want to offer in-depth cultural courses, the time and resources are rarely available for offering exotic portions of artistic delicacies in school. (The program's motto is "We give you what school can't.") For young minds all too accustomed to digesting the intellectual equivalent of Pop Rocks, a sustained encounter with Chase and Co. is like feasting on cassoulet and crepes.

Besides the Friday-night Cine/Club, Art & Film for Teenagers offers visits to museums and art galleries on Saturdays, tickets to some of the West Coast's most coveted cultural events -- Mahler's Ninth at the San Francisco Symphony, Bellini's Norma at the San Francisco Opera, David Mamet plays at the American Conservatory Theatre -- during the week and a film workshop that teaches young students how to write, produce, and direct their own short films. (See "Make a Movie: Help Teenages Improve Their Vision.") Since the program started, Chase estimates, his events have attracted a collective audience of more than 5,000 students. Nearly 700 of them, from dozens of middle schools, high schools, and colleges, attend the weekly events.

A Palpable Payoff

Parents seeking hard evidence of the value of a cultural education don't have to look far. Students who excel in the Art & Film for Teenagers program have an enviable track record of getting into the college of their choice, many with scholarships. But that is just one of the many reasons Chase thinks young people should get involved.

"I believe you have a job as a teenager," he says as late-afternoon light slants through the windows of his painter's studio in San Francisco's Outer Mission district. "The job is to get yourself ready. For what, you don't know. But you have to get ready. And one of the ways you get ready is to immerse yourself within a framework of the most sophisticated culture available." Above the studio's sink is a large hand-painted sign with a single word: "Emerson." Although the sign originally advertised a drug company, it's not hard to hear the echo of Ralph Waldo Emerson's idea of self-reliance in Chase's own educational philosophy -- and in his life.

Chase was born in 1934 in the small Oklahoma town of Seminole, and his own craving for culture came in part from geographic necessity. He was the sort of student who spent most of his time in the library. "There was no culture there," he says. "No understanding of the wider world. I was an Art & Film student who didn't have Art & Film."

A year after finishing high school in 1951, Chase headed for Bard College, north of New York City. It was in the this stimulating environment -- as has been known to happen -- that his native intellectual curiosity was fanned into flames. After graduating with a sense of his own artistic possibilities, Chase returned with a purpose to Seminole. "By the time I finished college, I was astounded how dumb I had been in high school," he says. "I had no one to tell me anything. So I went back and begged my high school principal to let me teach the brightest kids all the things I hadn't known." He lasted a few days.

"I brought up the word atheism in class, a student told his parents, and I was fired for preaching sedition," he says with a laugh.

By his own count, Chase has trafficked in many careers, including dancing, painting, photography, opera set design, and filmmaking. Now, he likes to say, he's linked them up into something that uses all his talents. It would be tempting to read the previous sentence and see him as a man who somehow never found his creative calling, but that would be a mistake. As an opera set designer, he helped pioneer a form of set design using film as the primary scenery, which premiered at the Washington Opera, in Washington, DC, in 1969. And although he glides past the subject while discussing his background, he is a painter of national reputation, with dozens of one-man shows around the country to his credit and gallery representation.

"I've never met anyone quite like Ronald," says Susan Stauter, artistic director of the San Francisco Unified School District (SFUSD). "He is more than just a person who knows a great deal and is excited. He's a person who brings invaluable gifts as a true artist. These students are being mentored by a great American artist. And they pick up on that intuitively."

Stauter, who left her post as conservatory director of the renowned American Conservatory Theatre in 1993 to return to public education, says that Art & Film for Teenagers is the program we all wish we could have had growing up. "We are living in the stultifying era of testing, when things are memorized and repeated, and that's called education," she says. "But real education involves real engagement, which leads to levels of inquiry, which leads to creativity. Ronald is doing all of that with these kids."

From Wannabes to Gonnabes

One such student is Max Sokoloff, who has been attending the full range of Art & Film events for one year. Typically, he was thrown into the deep end of the cultural pool. "The first film [at Art & Film] I saw was Dr. Strangelove, which I liked very much -- particularly how we talked about the film afterward. Ronald doesn't talk down to people. He talks up to them. And he never puts anyone's ideas down."

Because Chase contends that when it comes to culture, every young person today is "at risk," he doesn't dumb down his selections any more than he talks down to the students. One night, he will present the director's cut of Apocalypse Now, and the next evening he will take the same audience to hear the San Francisco Symphony perform Mahler's demanding Ninth Symphony under the direction of Michael Tilson Thomas.

Though students in Art & Film for Teenagers occasionally debate the program's erudite entertainment choices, for Sokoloff, it all comes down to seeking out the highest possible stimulation. "I think a fourteen-year-old should be seeing intelligent films," he says. "Most people my age see only commercial films, which don't have visually interesting aspects and aren't very challenging."

Chase says he hasn't had one complaint about exposing young people to sophisticated movies or plays with adult themes. "Parents know what they're getting their kids into," he says. "We send out warnings in advance: 'If you think you're going to be disturbed by this, don't come.' But the irony, of course, is that the language in high school is worse than any language you'll ever see in any film. And the incidents described or gossiped about in school are worse than anything a child would ever contact in any kind of media."

The impressive range of cultural institutions Art & Film for Teenagers students attend free reflects Chase's deep connections in the Bay Area artistic community. But he says the relationship works both ways. "One of the major jobs of the symphony is to get a younger audience into the hall," he adds. "That's the next generation. I'm an instrument to help them do that."

A Piper Who Doesn't Need to Be Paid

Nearly half of Art & Film for Teenagers's $146,000 budget goes to the Film Workshop, but the return on investment has already paid off. Five weeks in a row last spring, Chase sent out an email announcing that some film festival somewhere in the world had accepted yet another student film made by a participant. "I've seen him use the Film Workshops to really draw out some of these incredibly bright but shy teenagers," says Frish Brandt, director of San Francisco's Fraenkel Gallery. "He really understands teenagers in a way that's very special. It's like he's a kind of Pied Piper saying to them, 'There's a big world out there. Get out and see everything you can, and don't be afraid of it.'"

Brandt, whose son, August, attends Chase's outings, is such a passionate advocate for the program that Brandt joined its board of directors last year and holds Art & Film for Teenagers events at the gallery, one of the best showplaces for photography in the country.

It's clear what students and parents get out of Art & Film for Teenagers, but what's in it for Chase? The program takes about three-quarters of his time -- in the past five years, he and his volunteers have organized an astonishing one hundred cultural events per year -- and there isn't a large stipend attached. The SFUSD's Susan Stauter thinks she knows the answer: "You can't overstate the importance of legacy in the lives of artists. They have something to say that is so profound and important. Clifford Odets said that life isn't printed on dollar bills, and I think legacies aren't, either. I think Ronald's legacy will be the future. He's helping create the next generation of thinkers and doers."

Educators in other parts of the country often express interest in Art & Film for Teenagers, but the big question is just how to export the program without first making clones of Chase and waiting seventy-odd years while they absorb a lifetime of culture. Instead of exporting Chase, it makes more sense for others to come to him. In 2005, three teachers from Jackson Middle School, in Portland, Oregon, spent three days with him in San Francisco to learn more about how he does what he does. "It was very interesting," says Stauter. "The principal heard about Ronald and asked the parents of the school to raise money to send the teachers." Other school districts, including Quebec's, have expressed interest in learning more about Chase and his work. "When I travel around and people ask me what a great arts program looks like, I tell them about Art & Film for Teenagers," Stauter adds.

Showing, Not Telling

Back in the Dolby Theatre, the credits have just rolled at the end of the Fellini film. Chase, looking almost monklike in a black shirt and black trousers, solicits impressions from the audience. Although it's nearly 10 P.M., his indefatigable energy enlivens the discussion. Like a performer, he prods his audience to keep up with him, while pausing to allow stragglers to catch up. No response is too silly, no insight too banal. When a student raises a hand, Chase doesn't say, "Yes," by way of acknowledgment, but, rather, "Please." It's a subtle difference, but for a young person, "please" is the invitation that "yes" can never be.

As the evening's event concludes, the young people in the audience are still listening intently to their Pied Piper. "One of the things that Fellini does best is that he doesn't tell you," says Chase, his profile sharp against the glowing movie screen behind him. "He shows you."