A Comfortable Truth: Well-Planned Classrooms Make a Difference

Kids don’t have to squirm to learn.

Your content has been saved!

Go to My Saved Content.

If we were to assemble a list of adjectives to describe school, comfortable would not make the cut. Many of the places where vital teaching occurs, if not designed expressly for physical torment, are infamously uninviting. The classic model for schools, where mentors must compete with discomfort, can be traced back hundreds of years to the "reading" and "writing" schools designed to give children the skills to access God's word in the Bible. Little wonder that the school benches from those days resembled church pews and that sterility and rigor were the order of the day.

Very little has changed. Most public schools today are twentieth-century adaptations of the schools in the original American colonies. In the industrial version, however, students became products to be passed from grade to grade until sufficiently educated to work in a factory. School buildings reflected this ultimate goal, with classroom after similar classroom aligned along each side of a corridor, and regimental rows of hard chairs symbolizing strict attention and serious purpose.

Nothing about the industrial-school model required comfort as a precondition for success. In fact, school comfort, through the introduction of seemingly superfluous elements, was often seen to militate against the high ideal of efficiency. Even though no research or evidence supports this idea, a myth persists to this day that an uncomfortable school is probably good because it creates self-disciplined kids, not pampered softies.

Though the industrial model was solidly in place as the educational standard, however, a parallel, progressive movement arose in the early 1900s that sought to humanize and personalize education. This philosophy survives and has gathered dedicated adherents along the way, but most mainstream educators at the time it was developed were unconvinced that change was needed, and schools remained much as they had always been. Even after almost a century, John Dewey's 1915 exhortation that "nature has not adapted the young animal to the narrow desk, the crowded curriculum, the silent absorption of complicated facts" remains largely unheard.

What is the rationale for justifying the lack of creature comfort in today's schools? Nothing more defensible than the old dodge "We've always done it that way." But schools wear out and are renovated or replaced by new structures. And architects know far more about how people live and work than they once did. So the factory model is slowly relegated to history, like the dinosaur it is. But questions of comfort and rigor remain unresolved. Should schools be comfortable, and if so, why? What follows are eight truths that can go a long way toward settling an argument that probably should have been arbitrated long ago.

Truth #1: Comfort Matters

A considerable body of research about environmental design shows the positive effect comfort can have on learning, human productivity, and creativity. As a result, over the past thirty years, major shifts in workplace, recreational, and home design have occurred. Whether it is Herman Miller's Aeron Chair, the Club World seating plans on British Airways jets, Panasonic's massage chairs, or the upgraded bedding installed by nearly every major hotel chain, comfort is the new black. Everywhere except schools.

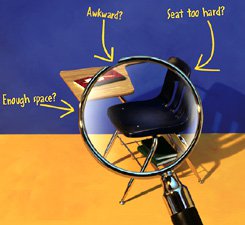

Truth #2: Some Pain, No Gain

The most basic comfort-related amenity is soft seating, and there's no longer any justification for the hard chairs on which students have to sit several hours each day. Some large school districts that spend more than $100 million on new school buildings will then nickel-and-dime on student chairs. With seating design, as with much else in life, you get what you pay for; a $50 chair will be no ergonomic bargain.

Truth #3: The Breathing and Learning Connection

Though air is (or should be) invisible, it is a major factor in human comfort, and indoor air quality is now recognized for its vital role in student and teacher performance. Thousands of hours are lost each year by students and teachers who suffer from asthma and other breathing difficulties. Making the air that students and teachers breathe in school cleaner and fresher is a comfort fundamental.

Truth #4: Louder Is Not Better

As anyone knows who has ended up too near the amplifiers at a rock concert, noise can wreak havoc on clear thinking. Schools can be made acoustically comfortable places in many ways. First, we must silence the horrible bells, those poorly disguised Pavlovian punishments. After all, both teachers and students have wristwatches, or there are clocks on classroom walls, so why should eardrums be punished? If being abruptly jarred every forty-five minutes or so created an atmosphere of learning and productivity, you'd hear bells jangling in every office and research institution.

Other ways to promote acoustical comfort include quiet air-conditioning systems that teachers and students don't have to shout over, audio enhancement in classes and performance areas, soft (unsqueaking) seating, sound-dampening drapes, acoustical treatments on walls and ceilings, and even irregular room shapes that dampen and redirect sound reverberations.

Truth #5: Cozy and Cheerful Wins Hearts and Minds

This one is for the architects who design schools and those who give out design awards. Large steel-and-glass atria work for airports, but they can siphon off construction money from the smaller, commodious spaces that work best for direct communication and learning. I recently visited a $130 million inner city steel-and-glass monster that trapped teachers and kids in small classrooms (many windowless) even as it allocated thousands of square feet to empty expanses.

And at the same time we discourage the temptation to create dramatic and photogenic but essentially useless spaces, can we also say good-bye to the "classic" classroom and replace it with a variety of small-group and large-group areas, each serving one or more modalities of teaching and learning? Places for independent study, project-based learning, peer tutoring, technology-aided teaching, cooperative learning, and team teaching all deserve dedicated designs.

Truth #6: Cafés Are Not Just for Grown-Ups

A school café (the antithesis of the typical school cafeteria) nourishes not only the body but also the spirit. Whereas a cafeteria is just a place to get food into kids and move them on, a café is a place where students might actually choose to be. Ideally, it would be much smaller than a big dining hall, accommodating no more than a hundred students at a time. There might be all-day access to a variety of healthy and nutritious refreshments and beverages, and comfortable chairs and small tables could accommodate groups of four or bistro-type seating for individuals or two students at a time.

The area could also feature student artwork, plus newspapers and other casual reading materials, as well as good views to greenery and vistas where possible. Look into almost any popular city café; working people use such places as ad hoc study halls, and so can students. As with other comfort concepts in this article, such an environment may seem unlikely in the workaday world of public education, but if we can't imagine the ideal, we'll never evolve the real.

Truth #7: Comfort Is Important Outside, Too

Sadly, very little thought is given to planning outdoor areas as true extensions of the learning experience in schools. (Thus, staring forlornly out of windows remains a staple of classroom behavior.) Here are some ways to extend the notion of comfort beyond the school building itself: Connect most principal learning areas directly with outdoor terraces furnished with weatherproof tables and chairs for project work and social gathering, create a natural outdoor amphitheater for music and performance, develop student-maintained vegetable and flower gardens, develop water features such as reflecting pools or ecoponds, and plant lots of trees for shade and aesthetics.

Truth #8: Emotions Count in Comfort

One of the most uncomfortable things about schools is the degree to which students feel anonymous in them. Yet although a movement to reduce the size of schools gains ground, we continue to build larger and larger schools that fly in the face of research showing school size as the most important factor (after family income) in determining student performance.

Luckily, all is not lost: A large school can be broken down into a series of small learning communities. (See "High Tech High," March 2007.) If such communities can be designed to be mostly self-contained and limited to no more than 125 students each, they can become emotional safe havens for students. Emotional comfort is the sine qua non of education, so it is difficult to overemphasize the need to create environments where students can feel both secure and significant.

Once we accept these eight truths, we can begin working our way toward creating comfortable and effective schools where learning is the focus and misguided nostalgia for the rigid "way it was" is relegated to the trash heap of history along with such discredited antiquities as caning and dunce caps.