A Common Language Creates an Uncommon Bond: Students Learn to Speak Japanese

An innovative program teaches kids it’s never too early to learn a foreign language.

Your content has been saved!

Go to My Saved Content.

The two fifth-grade boys have been living together for a week, with Yuta as the guest. Paired up by a school exchange program, they eat the same meals, they take the same classes, and they -- unlike Mason's mother -- speak the same language: Japanese.

A Model Program

Mason attends Richmond Elementary School in Portland, Oregon, a school that, along with Mt. Tabor Middle School and Grant High School, houses a fifteen-year-old Japanese language partial-immersion magnet program that researchers from the Center for Applied Linguistics have called a model for language learning. Students follow the Oregon state curriculum, using Japanese for half the day and English for the other half. On graduation from the program, which starts in kindergarten and goes through twelfth grade, they have completed their state requirements and acquired a language as well. Mason's mother, Aimee Virnig, says, "Japanese is an extra for us. It just happens. I can't imagine how wonderful it would be to graduate from school with such a real skill."

A Real-World Classroom Approach

Portland's Japanese Magnet Program (JMP) concentrates on putting the real world into language education. The program values authentic communication over parroted textbook "conversations." Three key components make language relevant: partial immersion from an early age, modeling by native speakers, and cultural exchanges.

Studies show that studying language at an early age can encourage brain development. In "What Parents Want to Know About Foreign Language Immersion Programs," Tara W. Fortune and Diane J. Tedick write, "It has been suggested that the very processes [immersion] learners need to use to make sense of the teacher's meaning make them pay closer attention and think harder. These processes, in turn, appear to have a positive effect on cognitive development."

To show students language modeled by native speakers, each classroom obtains a Japanese aide through the nonprofit Amity Institute's teaching exchanges. Interaction with the aides not only provides modeling of language and manners, it provides modeling of tolerance, says kindergarten teacher Amy Grover. "Children are quick to mirror respect for different ways of doing things."

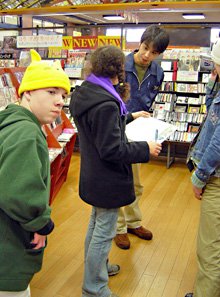

Student exchanges between the two countries also promote interaction with native speakers, and they keep students interested as they grow older. "As students move into adolescence," says district immersion coordinator Michael Bacon, "the motivation level will naturally wane. For most of these students, they didn't choose this [program] in kindergarten. It doesn't mean anything unless they've had a meaningful language experience outside the classroom." In the fall of fifth grade, Japanese students from the Katoh Elementary School in Numazu, near Tokyo, come to Portland. The following summer, the same Portland class visits Japan, visiting their Japanese friends near Tokyo and traveling to such locations as Kobe, Kyoto, and Sapporo.

Portland students also visit Japan in eighth grade for a two-week research residency, in which each student completes an interdisciplinary academic project. In Japan, students are based in the small agricultural town of Santo, in Hyogo prefecture, from which they explore the country, researching subjects such as geisha culture and swordmaking. High school freshman Kaia Range recalls making connections with native speakers on the train. "I asked [an elderly woman] a question about my homework and we got to talking," she says. "I didn't understand everything, but I got major things -- she pointed out where she was born and told me about how much snow there was when she was little." In the summer after eighth grade, a delegation of Santo townspeople visits the students in Portland.

Technology as well as travel connects students to Japan. In third grade, students learn to use the roman characters on the computer keyboard to make all three types of Japanese characters: hiragana, a phonetic system used for traditional Japanese language; katakana, a phonetic system used for foreign words; and kanji, a system based on Chinese ideograms in which each symbol represents an entire word. They then compose e-mail, which gives them a chance to use written Japanese in an authentic situation. Students begin e-mailing with exchange buddies in fifth grade. At the beginning of eighth grade, they write formal e-mail letters to Japanese experts, asking for help with project research and making sure to adhere to Japanese correspondence conventions such as the initial seasonal reference.

"Konnichiwa, hajimete no yukiga chyoto futta no de minna wa totemo ureshikatta desu. So shite, takusan no hito ga chisana yuki daruma wo tsukute yuki ga sen moshiteimashita. Keredomo, ima zenbu nakunate shimaimashita," begins one e-mail from students Anna Colon and Megan Warner.

Translated, this reads:

"Hello, we just had our first short snow fall and everyone was delighted. So many of us made small snowmen and had a snowball fight. But now the snow is all gone."

Students also learn to conduct Japanese Internet research. Fourth-grade teacher Atsuko Ando teaches her class to search with Japanese characters rather than phonetic English spellings. She is particularly fond of a site called Kids Goo, which enriches vocabulary by displaying each result in katakana, hiragana, and kanji. Access to a Japanese World Wide Web gives students an insider's view of the culture.

Teaching the insider's view is important, as many students have no Japanese heritage. The program reflects the demographics of Portland: 60 percent Caucasian, 20 percent Asian, and 10 percent African American, with some Hispanic and Native American students. Often, parents choose the program because it emphasizes cultural tolerance. "My mom entered me in the program because she knew I would be growing up in a society where intercultural communication would be incredibly important," says Noel Miller, a senior and future international studies major.

Others believe that studying a language helps children who are not textbook learners. Aimee Virnig says, "My eldest is a vocal learner, and this is something where you're rewarded for speaking. This is something he can excel at." Denise Van Leuven's older daughter "needs input from more sensory areas. Reading and writing are difficult for her. But kanji and katakana and hiragana are not difficult for her to write; English is. Having those two ways to come at one subject has been a big help to her."

The dedication of JMP parents, who call themselves Oya No Kai ("parent group"), makes much of this program possible. The nonprofit group's active fundraising ensures that every child can go on the fifth- and eighth-grade trips. Oya No Kai has also paid for school supplies and curriculum consultants, and has lobbied the school board to promote the program. The group sponsors Japanese interns, finding them host families and helping with visas, and it coordinates home stays when the Japanese students visit Portland.

The Road Ahead

Student Karin Loch did her part during the 2003 Omiyage Banashi, or "Souvenir Stories" meeting, in which students give presentations to the community about the eighth-grade trip and the magnet program.

"It was our proficiency in the Japanese language and culture that made the difference," Loch said. "Using our adopted language we were able to connect with, learn from, and laugh with our host families. Using our Japanese, we became not just observers, but players on the stage of life."