Education at Risk: Fallout from a Flawed Report

Nearly a quarter century ago, “A Nation at Risk” hit our schools like a brick dropped from a penthouse window. One problem: The landmark document that still shapes our national debate on education was misquoted, misinterpreted, and often dead wrong.

Your content has been saved!

Go to My Saved Content.

We hear a lot these days about the catastrophic state of American public schools. According to pundits' dire pronouncements, our kids supposedly compare terribly when ranked academically against all others in the world. Politicians ask us to take a stand: Are we for, or against, school reform?

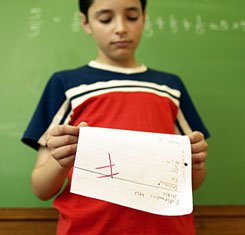

Standing for reform apparently means supporting rigorous testing, a back-to-basics curriculum, higher standards, more homework, more science and math, more phonics, something called accountability, and a host of other often daunting initiatives. Some educators worry about the fallout from these measures, such as the proliferating plague of standardized testing, but don't know how to oppose them without casting themselves as obstructionists clinging to a failed status quo.

Actually, however, according to Hoover Lydell, special assistant to the interim superintendent of the San Francisco Unified School District, "there is no such thing as the status quo. There never has been. What you hear today are today's ideas for school reform. In the past, there were other ideas. In the future, there will be still others. There's always school reform."

In short, it's never really a choice between supporting or rejecting school reform. It is, or should be, a choice between this reform and that reform. Yet today, a movement that stretches back several decades has narrowed us down to a single set of take-'em-or-leave-'em initiatives. How did this happen?

Well, it didn't "just happen." What we now call school reform isn't the product of a gradual consensus emerging among educators about how kids learn; it's a political movement that grew out of one seed planted in 1983. I became aware of this fact some years ago, when I started writing about education issues and found that every reform initiative I read about -- standards, testing, whatever -- referred me back to a seminal text entitled "A Nation at Risk."

Naturally, I assumed this bible of school reform was a scientific research study full of charts and data that proved something. Yet when I finally looked it up, I found a thirty-page political document issued by the National Commission on Excellence in Education, a group convened by Ronald Reagan's secretary of education, Terrell Bell.

This Means War!

The heart of the document is an indictment that lambastes America for letting schools slip into precipitous decline but praises the nation's good heart, great potential, and mighty past. No paraphrase can do justice to its tone, so here's a verbatim sample: "Our Nation is at risk . . . . The educational foundations of our society are presently being eroded by a rising tide of mediocrity that threatens our very future as a Nation and a people . . . . If an unfriendly foreign power had attempted to impose on America the mediocre educational performance that exists today, we might well have viewed it as an act of war . . . . We have, in effect, been committing an act of unthinking, unilateral educational disarmament . . . ."

Hear that, folks? Our very future. The Nation threatened!

Well, the rhetoric reflected the times. It was 1983; the Cold War was in full flower, and Reagan had swept into office on a promise to confront the Soviets. This stand had won him strong support -- among men.

But Reagan had a couple of political problems. First, polls indicated that women still tilted toward the Democrats, who owned such close-to-home issues as housing, health, and education. Second, the U.S. economy was tanking. And it wasn't our enemies driving our industries into the ground, but rather our allies, Japan and Germany.

In this anxious context, Bell put together an eighteen-member commission to report on the quality of education in America. Through the U.S. Department of Education's National Commission on Excellence in Education, he hoped to link the country's economic woes to the state of our schools. Bell got all he wanted and more.

When the report was released in April 1983, it claimed that American students were plummeting academically, that schools suffered from uneven standards, and that teachers were not prepared. The report noted that our economy and national security would crumble if something weren't done. But the sobering report received immediate publicity for an almost comically accidental reason.

As commission member Gerald Holton recalls, Reagan thanked the commissioners at a White House ceremony for endorsing school prayer, vouchers, and the elimination of the Department of Education. In fact, the newly printed blue-cover report never mentioned these pet passions of the president. "The one important reader of the report had apparently not read it after all," Holton said. Reagan had pulled a fast one, for political gain.

Reporters fell on the report like a pack of hungry dogs. The next day, "A Nation at Risk" made the front pages.

Once launched, the report, which warned of "a rising level of mediocrity," took off like wildfire. During the next month, the Washington Post alone ran some two dozen stories about it, and the buzz kept spreading. Although Reagan counselor (and, later, attorney general) Edwin Meese III urged him to reject the report because it undermined the president's basic education agenda -- to get government out of education -- White House advisers Jim Baker and Michael Deaver argued that "A Nation at Risk" provided good campaign fodder.

Reagan agreed, and, in his second run for the presidency, he gave fifty-one speeches calling for tough school reform. The "high political payoff," Bell wrote in his memoir, "stole the education issue from Walter Mondale -- and it cost us nothing."

What made "A Nation at Risk" so useful to Reagan? For one thing, its language echoed the get-tough rhetoric of the growing conservative movement. For another, its diagnosis lent color to the charge that, under liberals, American education had dissolved into a mush of self-esteem classes.

In truth, "A Nation at Risk" could have been read as almost any sort of document. Basically, it just called for "More!" -- more science, more math, more art, more humanities, more social studies, more school days, more hours, more homework, more basics, more higher-order thinking, more lower-order thinking, more creativity, more everything.

The document had, however, been commissioned by the Reagan White House, so conservative Republicans controlled its interpretation and uses. What they zeroed in on was the notion of failing schools as a national-security crisis. Republican ideas for school reform became a charge against a shadowy enemy, a kind of war on mediocrity.

By the end of the decade, Republicans had erased whatever advantage Democrats once enjoyed on education and other classic "women's issues." As Peter Schrag later noted in The Nation, Reagan-era conservatives, "with the help of business leaders like IBM chairman Lou Gerstner, managed to convert a whole range of liberally oriented children's issues . . . into a debate focused almost exclusively on education and tougher-standards school reform."

The Inconvenient Sandia Report

From the start, however, some doubts must have risen about the crisis rhetoric, because in 1990, Admiral James Watkins, the secretary of energy (yes, energy), commissioned the Sandia Laboratories in New Mexico to document the decline with some actual data.

Systems scientists there produced a study consisting almost entirely of charts, tables, and graphs, plus brief analyses of what the numbers signified, which amounted to a major "Oops!" As their puzzled preface put it, "To our surprise, on nearly every measure, we found steady or slightly improving trends."

One section, for example, analyzed SAT scores between the late 1970s and 1990, a period when those scores slipped markedly. ("A Nation at Risk" spotlighted the decline of scores from 1963 to 1980 as dead-bang evidence of failing schools.) The Sandia report, however, broke the scores down by various subgroups, and something astonishing emerged. Nearly every subgroup -- ethnic minorities, rich kids, poor kids, middle class kids, top students, average students, low-ranked students -- held steady or improved during those years. Yet overall scores dropped. How could that be?

Simple -- statisticians call it Simpson's paradox: The average can change in one direction while all the subgroups change in the opposite direction if proportions among the subgroups are changing. Early in the period studied, only top students took the test. But during those twenty years, the pool of test takers expanded to include many lower-ranked students. Because the proportion of top students to all students was shrinking, the scores inevitably dropped. That decline signified not failure but rather progress toward what had been a national goal: extending educational opportunities to a broader range of the population.

By then, however, catastrophically failing schools had become a political necessity. George H.W. Bush campaigned to replace Reagan as president on a promise to confront the crisis. He had just called an education summit to tackle it, so there simply had to be a crisis.

The government never released the Sandia report. It went into peer review and there died a quiet death. Hardly anyone else knew it even existed until, in 1993, the Journal of Educational Research, read by only a small group of specialists, printed the report.

Getting Educators Out of Education

In 1989, Bush convened his education summit at the University of Virginia. Astonishingly, no teachers, professional educators, cognitive scientists, or learning experts were invited. The group that met to shape the future of American education consisted entirely of state governors. Education was too important, it seemed, to leave to educators.

School reform, as formulated by the summit, moved so forcefully onto the nation's political agenda that, in the 1992 presidential campaign, Bill Clinton had to promise to outtough Bush on education. As president, Clinton steered through Congress a bill called Goals 2000 that largely co-opted the policies that came out of the 1989 Bush summit.

After the 2000 election, George W. Bush dubbed himself America's "educator in chief," and until terrorism hijacked the national agenda, he was staking his presidency on a school-reform package known as the No Child Left Behind Act, a bill that -- as every teacher knows -- dominates the course of public education in America today.

School reform is not a settled issue, however, and the ongoing debate about how best to go about it reflects a larger struggle between two competing ideologies. The many initiatives discussed for changing public education -- accountability, standards, standardized testing, homework, arts in the curriculum, and so on -- comprise one side of that debate.

Consider the analogy, for example, between liberal and conservative approaches to crime and to education. On crime, one side says, "Start with the criminal. Ask what turns people into criminals, what motivates criminals, how we intervene in that process, and how we can alter the conditions that promote transgression." The other approach says, "Never mind who the criminals are: State the rules, catch the violators, and punish them hard so they won't do it again."

When it comes to schools, one side says, "Start with the student. Ask what motivates kids, what blocks them, what gets them to muster their own best learning resources." The other approach says, "Never mind each particular student's wants and needs: Post the curricula, test all students, and punish those who fail."

Testing provides another revealing example. Teachers have always used myriad formal and informal tools to see whether kids are learning what is being taught. No one is against assessment. But testing in the context of today's school reform is not about finding out what kids know; it's about who gets the test results.

Only on-site teachers can really make a broad ongoing assessment that gets at a range of achievements and takes the individual into account. By contrast, uniform standardized testing whose outcomes can be expressed as simple numbers allows someone far away to compare whole schools without ever seeing or speaking to an actual student. It facilitates the bureaucratization of education and enables politicians, not educators, to control schools more effectively.

James Harvey, a member of the commission that produced "A Nation at Risk," expresses concern about the uses made of the report and the direction it has given to school reform. Today, he says, "educational decisions have been moved as far as possible from the classroom. Federal officials are now in a position to make decisions that would have been unimaginable even two years ago. They've established the criteria for disciplining schools, removing principals and teachers, and even defining appropriate curriculum for American classrooms."

Reform, Not Improve

Bush Sr. launched the idea of a national education policy shaped at the federal level by politicians. Clinton sealed it, and our current president built on this foundation by introducing a punitive model for enforcing national goals. Earlier education activists had thought to achieve outcomes through targeted spending on the theory that where funding flows, school improvement flourishes. The new strategy hopes to achieve outcomes through targeted budget cutting -- on the theory that withholding money from failed programs forces them to shape up.

Which approach will actually improve education? Here, I think, language can lead us astray. In everyday life, we use reform and improve as synonyms (think: "reformed sinner"), so when we hear "school reform," we think "school improvement." Actually, reform means nothing more than "alter the form of." Whether a particular alteration is an improvement depends on what is altered and who's doing the judging. Different people will have different opinions. Every proposed change, therefore, calls for discussion.

The necessary discussion cannot be held unless the real alternatives are on the table. Today, essentially three currents of education reform compete with each other. One sees inspiration and motivation as the keys to better education. Reform in this direction starts by asking, "What will draw the best minds of our generation into teaching? What will spark great teachers to go beyond the minimum? What will motivate kids to learn and keep coming back to school?"

In this direction lie proposals for building schools around learners, gearing instruction to individual goals and learning styles, pointing education toward developing an ever-broader range of human capacities, and phasing in assessment tools that get at ever-subtler nuances of achievement. Overall, this approach promotes creative diversity as a social good.

A second current, the dominant one, sees discipline and structure as the keys to school improvement. Reform in this direction starts by asking, "What does the country need, what must all kids know to serve those needs, and how can we enforce the necessary learning?" In this direction, the curriculum comes first, schools are built around the curriculum, and students are required to fit themselves into a given structure, controlled from above. As a social good, it promotes national unity and strength. This is the road we're on now with NCLB.

A third possible direction goes back to diversity and individualism -- through privatization, including such mechanisms as tuition tax credits, vouchers (enabling students to opt out of the public school system), and home schooling. Proponents include well-funded private groups such as the Cato Institute that frankly promote a free-enterprise model for schooling: Anyone who wants education should pay for it and should have the right to buy whatever educational product he or she desires.

What's Next?

Don't be shocked if NCLB ends up channeling American education into that third current, even though it seems like part of the mainstream get-tough approach. Educational researcher Gerald Bracey, author of Reading Educational Research: How to Avoid Getting Statistically Snookered, writes in Stanford magazine that "NCLB aims to shrink the public sector, transfer large sums of public money to the private sector, weaken or destroy two Democratic power bases -- the teachers' unions -- and provide vouchers to let students attend private schools at public expense."

Why? Because NCLB is set up to label most American public schools as failures in the next six or seven years. Once a school flunks, this legislation sets parents free to send their children to a school deemed successful. But herds of students moving from failed schools to (fewer) successful ones are likely to sink the latter. And then what? Then, says NCLB, the state takes over.

And there's the rub. Can "the state" -- that is, bureaucrats -- run schools better than professional educators? What if they fail, too? What's plan C?

NCLB does not specify plan C. Apparently, that decision will be made when the time comes. But with some $500 billion per year -- the sum total of all our K-12 education spending in this country -- at stake, and with politicians' hands on all the levers, you can be pretty certain the decision will not be made by those whose field of expertise is learning. It will be made by those whose field of expertise is power.

Tamim Ansary writes and lectures about Afghanistan, Islamic history, democracy, schooling and learning, fiction and the writing process, and other issues and directs the San Francisco Writers Workshop.

"A Nation at Risk" (1983)

What the report claimed:

- American students are never first and frequently last academically compared to students in other industrialized nations.

- American student achievement declined dramatically after Russia launched Sputnik, and hit bottom in the early 1980s.

- SAT scores fell markedly between 1960 and 1980.

- Student achievement levels in science were declining steadily.

- Business and the military were spending millions on remedial education for new hires and recruits.

The Sandia Report (1990)

What was actually happening:

- Between 1975 and 1988, average SAT scores went up or held steady for every student subgroup.

- Between 1977 and 1988, math proficiency among seventeen-year-olds improved slightly for whites, notably for minorities.

- Between 1971 and 1988, reading skills among all student subgroups held steady or improved.

- Between 1977 and 1988, in science, the number of seventeen-year-olds at or above basic competency levels stayed the same or improved slightly.

- Between 1970 and 1988, the number of twenty-two-year-old Americans with bachelor degrees increased every year; the United States led all developed nations in 1988.