Master Classroom: Designs Inspired by Creative Minds

A team of architects who specialize in learning spaces want to let Leonardo da Vinci, Albert Einstein, and Jamie Oliver show you the future of classroom design.

Your content has been saved!

Go to My Saved Content.

The industrial era had a long run, both gritty and great, but it's over. The problem is, someone forgot to tell the education establishment. In schools across America, the factory model is still alive, and nowhere is it more readily apparent than in the classroom.

In these little factories, every day we can find teachers encouraged (and often compelled) to mass produce learning and marginalize the differences in aptitudes, interests, and abilities. The industrial-age classroom was not all bad in its time; after all, America did all right in its heyday. But this model is no place to prepare students for the fast-changing global society they will inherit.

As school planners and architects, we challenge communities and clients to explain why a regimental row of desks facing a chalkboard needs to remain as a school's primary building block. We ask them to review the eighteen modes of learning (see www.designshare.com) that educators accept as essential for success in today's world, so they can see how a traditional classroom can accommodate only two or three of them.

But if not the old-style classroom, then what? How should the model evolve? In exploring this question with educators around the world, we've come up with at least three distinct "studios." To help us, we called on illustrious thinkers who shaped the ideas of their times: Leonardo da Vinci, Albert Einstein, and a modern master named Jamie Oliver. Destroying the traditional learning environment and creating something entirely new was a major challenge for our three maestros, but here's what they came up with.

The Da Vinci Studio: Action Through Synthesis of Knowledge

In the coming years, no educational paradigm shift will be more forcefully felt than the enrichment of disciplines through cross-pollination. Context and connection are fundamentally changing the way teachers teach and students learn. Not only are we hurtling at breakneck speed into an era in which traditional hard lines between the arts and the sciences are blurring, but we are also doing so with one eye firmly fixed on the way design can help the left brain and the right brain work in harmony.

Leonardo da Vinci has already provided a highly workable model for how this shift might be accomplished. In da Vinci's world, the lines between the disciplines, pervasive in today's schools, were absent; the works he did as a scientist, mathematician, and artist all informed the other efforts. No wonder one can look at his scientific drawings and wonder whether they were meant to be works of art and at his artwork and marvel at its scientific rigor. This kind of free-flowing interchange was accomplished in a workplace that was part artist's studio, part science lab, and part model-building shop.

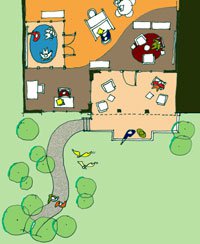

So, what would a modern-day da Vinci studio look like as a classroom? Imagine a place with lots of daylight and directed artificial light, connection to an outdoor deck through wide or rolling doors (for messy projects), access to water, power supplied from a floor or ceiling grid, a wireless computer network, lots of storage, a floor finish that is hard to damage, high ceilings, places to display finished projects, reasonable acoustic separation, and transparency to the inside and outside with the potential for good views and vistas.

To take full advantage of today's da Vinci studio, teachers would need to collaborate more, offer students the opportunity to work on real projects, and encourage cross-disciplinary thinking in a way rarely seen within the four walls of traditional, unrevised schools.

The Einstein Studio: Creative Reflection and Inspired Collaboration

Albert Einstein's workplace was more study than studio. Preferring solitude and connections to nature, Einstein gave himself lots of time to stay in his own head. Because so much of what he did was cerebral, his inspiration could have come during quiet walks and in places other than his primary workplace (among other activities, he loved sailing on Long Island's Peconic Bay).

His official workplace may simply have let him develop ideas he had generated elsewhere. And so, when we talk about the Einstein studio today, we do so more in a metaphorical sense than as a way to actually duplicate Einstein's workplace in the modern school.

We can imagine that today's Einstein studio might include a place that encourages creative reflection, an inspiring setting not sealed off from the world outside or from those real problems and issues that must always have some place in abstract theorizing. To imagine an Einsteinian classroom, conjure the various ways the main lobby of a five-star hotel is furnished: It welcomes people alone or in small groups, it offers comfortable furnishings, it may nurture aspiration and inspiration with high ceilings, lots of glass, and easy connection to natural elements and water features, and it creates zones of privacy that remain firmly connected to the activity throughout the larger space.

A school isn't a five-star hotel, of course, but planners can still draw on this vision for inspiration despite budgetary constraints. The Einstein studio can also be a movable feast, a portable state of mind to be re-created around a shade tree in the spring or on a class nature walk.

Think also about visually connecting the Einstein and da Vinci studios -- one a venue for inspiration, the other a place for inspired action.

The Jamie Oliver Studio: Nourishing Mind, Body, and Spirit

Having spent some time learning from the masters of the past, whose legacy spans centuries of human history, we now turn to an unlikely hero from today's world: young English chef and entrepreneur Jamie Oliver. Using food preparation, a venerable art form, Oliver gives people a reason to celebrate a common goal -- to eat well and be healthy.

As a de facto educator, he speaks to members of the young generation about realizing their potential and making good decisions, about personal choice and real alternatives to success found in unfamiliar places far from the beaten path. But in an era that values the notion of lifelong learning, Oliver's message also resonates powerfully with other age groups.

In today's school, the Oliver studio would be a teaching kitchen connected to a cafe. With student participation as the centerpiece of its operations, it would contain a mirrored cooking station visible to the whole "class" and small, round cafe tables with comfortable chairs. Like the Einstein studio (but unlike the da Vinci studio), the Oliver studio could occupy a space with soft edges. That means it doesn't need to be defined by four walls, but might spill over into circulation areas and also onto outdoor patios. As with the other studios, the Oliver studio's design is limited only by the constraints of a particular site, the needs of the community it serves, and the imagination of its designer.

Money is a factor, of course, as it always is, but imagination is a powerful currency not often accounted for in the red and black ink of budgets. As a place for physical, emotional, and spiritual nourishment, the Oliver studio can be located so that it serves both the da Vinci and Einstein studios.

Once you begin to think of how creative thinkers actually work, the classroom as factory becomes a mere enforcer of conformity, and far more satisfying possibilities arise. Unless you have the good luck to be able to start from scratch, the trick is to adapt new design ideas into existing spaces. It's a tricky trick, but one well worth mastering.

Prakash Nair, Randall Fielding, and Jeffery Lackney are futurists and architects with Fielding Nair International, which has developed award-winning schools around the world. Write to them at prakash@designshare.com, fielding@designshare.com, and lackney@designshare.com.

SIDEBAR: 10 Ways to Outthink the Box

1. Discard the mental model: Remember that the classroom "box" exists not only as a physical place but as a mental one as well. Determine to get rid of an outdated idea.

2. Assign a group project: Have your students research school design (use our Web site, DesignShare.com, as a resource) to figure out an alternative way to furnish the box.

3. Develop an "activities matrix": Decide which of the eighteen learning modalities (search for that term on our Web site to find the list) can be reasonably accommodated in the classroom spaces.

4. Soft is good: Make sure the plan includes soft seating -- beanbag chairs, cushions, a couch, and upholstered chairs are all worth considering -- for a less rigid feel.

5. Pretest the design: Using graph paper and templates for furniture, examine the various ways the room can be arranged to facilitate different modes of learning.

6. Raise funds, get used furniture, seek merchant donations: Develop and implement a plan to raise money for new furniture, or (better still) approach local corporations and other businesses for donations of their used furniture that matches what your desired plan calls for. Ask your local home-improvement store to donate paint and equipment to build display boards, shelves, windowsills, and so on.

7. Make it green: Use this project as a conscious exercise in environmental responsibility by choosing indigenous materials, connecting with outdoors and nature (if possible), and expending minimal resources.

8. Do it yourself: If students build it, they will love it, take care of it, and feel the satisfaction of passing a new environment on to future classes.

9. Down with walls: If you have a bit of renovation money, take down some walls to facilitate team teaching, create social space, and break out of corridors.

10. New space, new practices: Let your teaching style, and the way students learn, take advantage of what you have created.