Safe Schools Ambassadors Help Keep the Peace on Campus

Students can effectively discourage bad behavior among their peers.

Your content has been saved!

Go to My Saved Content.

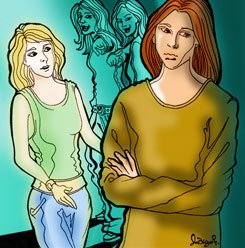

Earlier this year, when a Texas high school student started dancing by herself to background music during a student meeting, some classmates began to taunt her with whispers, jokes, and laughter. But the bullies quickly became silent when one of their peers joined the girl, who was enrolled in the school's special education program.

"Some snickering started," recalls Don Shigekawa, who coordinates safe and drug-free schools for the Clear Creek Independent School District, southeast of Houston. "One of our ambassadors got up and started dancing, and then another one did, and then some other students did. In that flash of a moment, it turned into an acceptable thing to do."

Bullying -- from verbal teasing to physical violence -- isn't a new plight among children, and it remains pervasive in the United States. According to an April 2007 study by Stanford University and the Lucile Packard Children's Hospital, nine out of ten elementary school students had been bullied by peers and six out of ten had engaged in some type of bullying in the previous year. A former high school principal has come up with a proactive solution to this enormous problem, a fix that's remarkably effective in schools nationwide: Get kids involved in stopping the bullying.

The Texas incident is a shining example of this strategy. The students who stood up for the girl being taunted were members of Safe School Ambassadors, an eight-year-old program run by the California-based Community Matters. To date, 650 schools in thirty-one states have made use of Safe School Ambassadors, says the nonprofit organization's founder, Rick Phillips. The program identifies students in grades 4-12 who are leaders in their social circles and trains them in constructive ways to prevent cruelty and violence.

"There are a lot of bystanders who are afraid to open their mouths because the bullying could be turned against them," says Phillips, coauthor of the book Safe School Ambassadors: Harnessing Student Power to Stop Bullying and Violence. "There's a code of silence. You have to start with kids who aren't afraid to buck the trend. They are not always the 4.0-grade-point-average, student-council kids. They're diverse. They come from all the different cliques."

Schools choose their ambassadors based on recommendations from teachers, staff, and sometimes other students. After they've made the selections, trainers from Community Matters teach the kids to use nonviolent communication skills to curb bullying of all types, including taunting, insults, gossip, harassment, and fighting. Strategies may be as simple as changing the subject or distracting the bully. For example, a student might stop an argument in the bathroom just by giving combatants the helpful heads-up, "I think someone is coming," whether or not anyone of authority actually is on the way.

The initial two-day training, which schools can launch and support with federal Safe and Drug-Free Schools funding (Title IV of the No Child Left Behind Act), costs $4,300 for a group of thirty to forty students and six to eight educators. The fees include training materials and ongoing coaching and support after the seminar, Phillips says.

Research shows that incidents of bullying decrease by half when students intervene. Wendy Craig and Debra Pepler, in their paper "Making a Difference in Bullying," found that peers are present for 85 percent of bullying episodes on campus. Though these bystanders step in only 11 percent of the time, when they do confront the bully, their chances of stopping the incident are about 50/50. Students have an advantage over teachers because they are often on the spot when bullying starts and have the option to act immediately, Phillips says.

Shigekawa reports that since his school district established the program in September 2007, he has seen significant reductions in these areas:

- assaults against students: 24 percent

- assaults against teachers: 60 percent

- weapons-related incidents: 28 percent

- drug- and alcohol-related incidents: 37 percent

- terroristic threats (threats that cause fear) to entire schools and individuals: 25 percent

Ambassadors meet regularly with one another, teachers, counselors, and program advisers to discuss incidents they have witnessed or prevented. To maintain their anonymity and effectiveness, students are encouraged not to discuss their efforts with the student body at large. "Students are not wearing a cap or hat or T-shirt that identifies them as ambassadors," Phillips says. "We feel it is important that they operate informally and in the moment. They see and hear things teachers do not."

Greg Lee, diversity coordinator at the William S. Hart Union High School District, in Santa Clarita, California, says some students are reluctant to take part because they fear being perceived as snitches. Lee explains, "At first, they think they're going to be asked to be hall monitors. But we're not asking them to leave their comfort zone or their social cliques. They're intervening within their comfort zones, with people they know. When they are informed they were selected because they are seen as natural leaders or people with influence within their peer group, they tend to rise to the occasion."

Lee concedes that operating in virtual anonymity can be difficult for some ambassadors, who do not receive extra credit or public recognition for their good deeds. "It's tough for some of them to work in the program without regular recognition. They don't get the kudos that some other student leaders get -- no yearbook picture, no bulletin board or PA announcements," Lee explains. "Some love the anonymous aspect of it, but I see it taking a toll on some others."

The student ambassadors have a lot to be proud of in the William S. Hart district, which enrolls 25,000 kids in grades 7-12. Lee credits the program, one component of a districtwide diversity initiative, with helping to reduce incidents related to cultural and racial insensitivity from fifty-three in 2006-07 to twenty in the school year that just ended. "But most of our bullying incidents are a result of poor social skills, not race," notes Lee. "It's socioeconomics and social cliques, and who fits in and who doesn't."

Melleny Hernandez, a senior in the district, says she became an ambassador four years ago because she wanted to help stop bullying. Since then, she's experienced the program's positive effects. "It's made all the students on campus more open with each other," adds Hernandez, who sometimes invites students outside her circle of friends to join their activities. "We have a lot of different races and groups, and they don't exclude each other as much."

Hernandez and her peers seem to reflect a larger trend among students to take antibullying efforts into their own hands. Although the examples are harder to cite, because they aren't affiliated with a national program, smaller-scale efforts are in place. After being asked to write a report about bullying, a student at Glenbard South High School, in Glen Ellyn, Illinois, organized a club called Genders Against Mean Experiences and Situations to promote healthy relationships and reduce behaviors related to bullying.

As one of the group's efforts, club members meet with incoming students to talk about bullying and to assure them it is unacceptable. "It lets those eighth graders know that there are people they can turn to for help," Assistant Principal Pam Petersen says.

Of course, student involvement of any kind does not abdicate teachers, administrators, support staff, or parents from their responsibilities. "Once a crisis is averted, it's incumbent on adults to make a long-term solution," Lee says, citing an incident on one high school campus in which a group of students were staking a claim to specific turf. Teachers and administrators halted the practice by holding activities in the same area. The students' "territory" was therefore appropriated for general use, which sent a message to everyone that they are welcome anywhere in the school.

Trudy Ludwig, author of My Secret Bully and several other books about the topic, says adults should also provide kids with literature that contains empathetic social messages. "We need to get them to notice bullying -- and to care," she adds. "We have to educate kids to see that they need to be part of the solution, not part of the problem. They have the power to step up and be heroes."

Whether that involves dancing, or starting a club, is entirely up to them.

Annemarie Mannion is a Chicago-based freelance writer.

Support Steps: How Teachers Can Prevent Bullying

Encouraging students to take a stand against, or merely cope with, the bullies in their midst provides educators with a bit of a challenge, so Edutopia.org asked three experts -- Safe School Ambassadors founder Rick Phillips and antibullying authors Trudy Ludwig and Brad Tassell -- what teachers can do to support kids. Here's what they suggest:

Be observant. Bullying often occurs in covert ways. Keeping a written record of students' verbal and body language can help teachers recognize subtle cues. Describing and naming what you see enhances your ability to notice negativity and disrespect. Watch for behaviors such as eye rolling, sarcastic or hostile tones of voice, and body movements that threaten or harass others. These include unwanted touching and exclusionary tactics, such as moving chairs to make it impossible for someone to sit somewhere.

Teach tolerance. Incorporate tolerance themes into existing lesson plans. If you are teaching reading or history, you can use books with fictional characters or real community leaders who have diverse backgrounds, ethnicities, and cultures. For example, Tassell's novel for middle school kids, Don't Feed the Bully, tells the story of a child who challenges mean kids at his school. Role-playing activities based on this or other books give students a chance to process, prepare, and practice how to handle different situations.

Reward kindness. Acknowledge good behavior by giving students attention, approval, and formal recognition. For example, schools in the William S. Hart Union High School District, in Santa Clarita, California, have rewarded their Safe School Ambassadors participants with activities, such as a bowling party, planned just for them.

Talk to the bully. When an unpleasant incident occurs, ask bullies to consider their motives and how their behavior affects others. Questions such as "What was wrong with your behavior?" and "What problem are you trying to solve?" can help bullies recognize that their interaction with others was inappropriate. You can find a full list of helpful questions in the book, Schools Where Everyone Belongs: Practical Strategies for Reducing Bullying, by Stan Davis with Julia Davis. -- AM

Videos on Violence: News Clips About Safe School Ambassadors

To learn more, watch these television-news video segments about bullying: