The Word and the World: Technology Aids English-Language Learners

A growing number of software programs and Web tools help educators teach academic English.

Your content has been saved!

Go to My Saved Content.

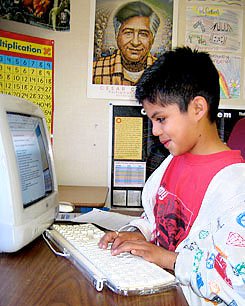

Students at Cinnabar Elementary School, in Petaluma, California, work under an encouraging computer lab banner that states, "Mistakes Welcome Here -- You can't learn without them!" That banner, along with brightly colored posters and an impressive array of computers, digital cameras, scanners, and printers, sets a vibrant scene. But it's the students who bring character and action to the fore with their laughter, curiosity, and multimedia productions.

Because English-language learners (ELLs) now make up half of the school's population, teachers there are looking for effective ways to teach them academic English. (See the school district's master plan for ELL students.) Amy Wegener-Taganashi, the school's English-language-development teacher, says an array of technology helps engage students and provides the structured one-on-one English practice they need. Cinnabar has computers in every classroom, and classes use the computer lab for multiweek projects. Additionally, upper-grade students can visit the lab during lunch to use the computers.

Read Naturally, a multimedia reading program that helps students develop English fluency, is one of the programs they use in the lab. Another application is Rosetta Stone language-learning software, which helps them associate images with English words and sentence structures to build their vocabularies. Wegener-Taganashi says of Rosetta Stone, "It's really great, because it's geared to individual students. The idea is that they are always being challenged."

Honing Skills

Wegener-Taganashi says software, online tools, and other technologies help students hone basic language skills they can later apply in authentic social settings. "The kids spend most of their day listening and not interacting with the language as much," she notes. But technology mixes things up, captures students' attention, and engages them in a way traditional classroom instruction doesn't.

Sixth grader Diego, who speaks Spanish at home but picked up English easily, says technology has improved his languages skills and makes school fun. "The computers helped me a lot," Diego says. "We go to the computer lab and make PowerPoint presentations and write a lot of letters and essays. I like writing on the computer better than writing with a pencil."

Cinnabar is not alone in its tech-aided quest to meet the needs of a rapidly growing population of nonnative English speakers in U.S. schools. Projections show that by 2015, one in three American students will be an English-language learner. The number of students learning English as a second language has already nearly tripled to more than 9.9 million students in the last two decades. Roughly 70 percent of these students are Spanish speakers, but the group includes speakers of more than 400 languages, from Arabic to Tagalog. As ELL needs increase at a pace that far outstrips most schools' human and financial resources, many are looking to technology to fill the gap.

Laying the Groundwork

There hasn't been a comprehensive study of the technologies teachers are using to aid K-12 English-language learners, but educators strongly recommend individual computer programs and other technologies because they say they accelerate the acquisition of phonics, vocabulary, fluency, and reading-comprehension skills and other language building blocks.

Alma Rodriguez, assistive-technology coordinator for the special education department of the Laredo Independent School District, in Laredo, Texas, uses a medley of technology products to bolster the English-language skills of its largely Spanish-speaking population. They include Scientific Learning's Reading Assistant, Kurzweil Educational Systems's Kurzweil 3000, Lexia Reading, and MindPlay's My Reading Coach to bolster students' English skills.

Kurzweil 3000 boosts accessibility to grade-level content because it can scan and read content in any text format and in multiple languages. Lexia Reading teaches phonics and phonemic awareness. My Reading Coach goes beyond phonics to address articulation. And Reading Assistant, a one-on-one guided oral-reading support program, has sophisticated speech-recognition software that helps children pronounce words correctly. The programs cost from hundreds to thousands of dollars for a license that grants use to a limited number of users or computers.

Rodriguez says Reading Assistant's stories are fun and hold the attention of what she calls today's "multisensory" students. The selections also support increasing levels of academic vocabulary with definitions, pronunciations, contextual sentences, and illustrations. Most important for teachers, the program can record audio of the students reading, makes corrections, documents errors, evaluates comprehension, and provides extensive data for monitoring student progress.

The results speak for themselves, Rodriguez says. With a password, she can access audio files of any district student reading aloud to monitor his or her progress over time. Teachers can even email the sound clips to parents. "The students can progress from reading twenty words per minute to seventy words per minute," Rodriguez says of Reading Assistant's results. "It's like magic."

Louise Dube, vice president and general manager for speech products at Scientific Learning, maker of Reading Assistant, says the software offers "individual, private, just-in-time coaching." She describes it as a supportive environment in which teachers don't ask students to read in front of their peers when they know the kids are not great readers yet.

Learning Language in Context

Others, however, aren't convinced that using such software is effective. Margaret Hawkins, a professor at the University of Wisconsin at Madison School of Education, says few classrooms have the equipment and few teachers have the training, flexibility, or motivation to mine the power of computers and the Web for language learning. "I see principals and teachers, many of whom are overwhelmed by this new influx of language learners, buying software and sitting kids at computers and saying, 'This one drills vocabulary or this one does this or that,'" she says. "When you sit a kid one-on-one at a computer, it's not a very good use of anybody's time."

Hawkins adds that students don't really acquire language by performing computer tasks divorced from an authentic learning environment. Instead, she says, they need social interactions that make them actively use language to negotiate meaning. In her view, much of today's language-learning software is rooted in old Second Language Acquisition and English as a Second Language research that treats listening, speaking, reading, and writing as separate areas and posits that students can learn general language out of context, then apply it specifically later.

"It's a throwback to looking at language as one monolithic thing that's made up of discrete parts, and if you can master those parts -- the sounds, symbols, and structures -- then you are going to be a competent language learner," she explains.

Hawkins says the most exciting use of technology for language learning is taking place outside of classrooms: A growing body of academic research is revealing the language-acquisition value of building teams, solving problems, and thinking critically through online games, chat rooms, and other Web-based interactions.

It suggests that there are several benefits to language learners from social online communication, such as more opportunities for expression and meaningful discourse than in face-to-face discussions, greater linguistic production overall, more student engagement, and more multidirectional (versus teacher-centered) interaction. But schools have been slow to view many of these Internet activities as educational, so community centers and other venues are taking the lead, Hawkins notes.

"We need to find a way to bridge the inside-school world and the outside-school world," she says. "The potential of technology for classrooms is huge, but schools are light-years behind what's out there."

Authentic Connections

Mark Warschauer, a professor of education and informatics at the University of California at Irvine, says the key is to use technologies that allow learners to focus in on text and to engage with real-life audiences and issues. "The biggest problem related to English-language learning is not so much developing oral-conversation skills, but gaining academic written-language skills," he explains. "One of the things that has been shown is that when students talk about things in online discussions, they use more complicated vocabulary, because it is easier to see what's been written by others and incorporate it into their own writing."

Basic Internet, word processing, and presentation technologies can facilitate authentic connections to the world. Warschauer cites student work at Mar Vista Elementary School, in Oxnard, California, as an example. Third and fifth graders there researched the lives and work of nearby strawberry-field laborers. For Project FRESA, they came up with research questions in English, translated them into Spanish to conduct interviews with the workers, and then translated the responses into English.

They wrote poetry about the workers, created graphs based on the data they collected, conducted online research, wrote letters to strawberry growers and government agencies requesting additional information, had online exchanges with students in Puerto Rico who were studying coffee-plantation conditions, and gave a community presentation to share their findings.

"That's an example of using a project to really immerse literacy activities in something that is culturally relevant to the students' lives," Warschauer says. "It gives them a chance to focus on text and what it means."

But it's also the type of project where the benefits -- creating an interest in computers, research and revision skills, real-life writing skills, and academic engagement -- may be too broad for current assessment tools. "The skills you learn with computers don't necessarily translate to the paper-and-pencil tests that have such high currency in our school systems right now," Warschauer notes.