It’s that time again—our yearly review of the research you should read, from the sneaky ways that inattention can spread in your classroom to the promises and perils of AI.

Sign up for our monthly newsletter, The Research Is In. Each item is carefully curated by our editors, and presented in a way that’s clear, concise, and practical. Staying on top of important discoveries in the learning sciences field has never been easier.

SubscribeWant to read it first? Here’s a recent edition:

The Research IS IN

This month: Our roundup of the most significant studies of 2024. Plus, some standout research highlights.

By The Numbers

The Cursive Comeback

As technology continues to transform the classroom, cursive is back in the mix.

A look back at an interesting story from earlier in the year: What’s the difference between a typed T and a handcrafted one? Both letters convey the same phonetic information, but to the brains of younger kids, in particular, there’s no comparison.

Teachers have long suspected what brain-imaging studies repeatedly confirm: When elementary-age children write letters by hand, a flicker of recognition crackles through neural circuitry in the brain linked to reading comprehension. The effect largely disappears when letters are typed or traced. In 2020, researchers studying 7th graders concluded that, when compared to typing, handwriting left telltale neural traces indicative of deeper learning, and 2021 and 2024 studies revealed similar findings in adults. Increasingly, writing by hand appears to improve retention at every age level.

But handwriting has had its doubters.

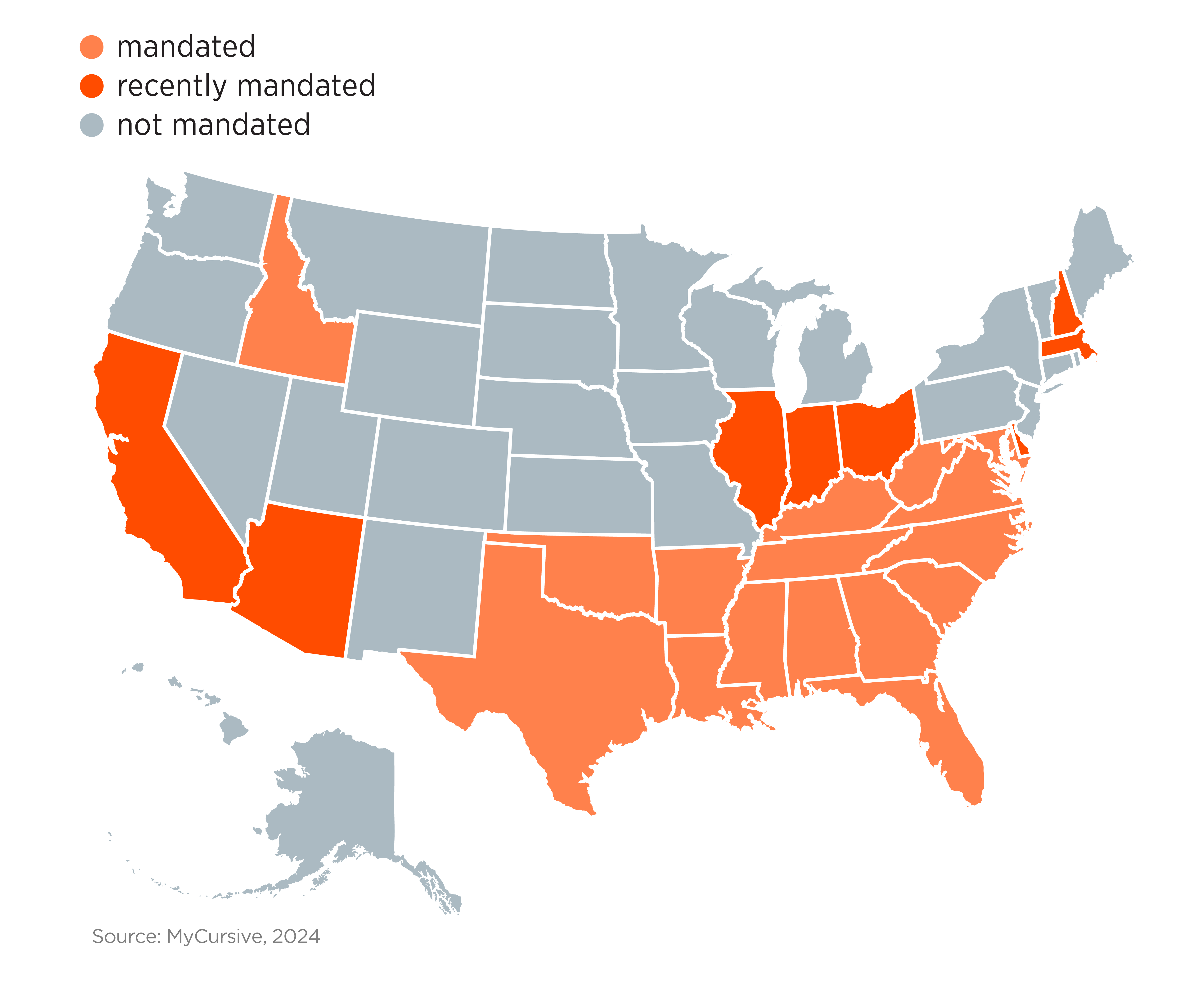

Overshadowed in the early 2000s by the rise of tablets, computers, and smartphones, handwriting of all kinds—including the looping characters of cursive script—began to disappear from U.S. classrooms. By 2016, only 14 states mandated cursive instruction in public school. Today, however, armed with new insights about the power of multisensory learning, 10 more states have joined the cause.

Even as ChatGPT promises another revolution, pens and pencils remain formidable tools for annotating texts, drawing to learn, and summarizing—and a healthy mix of old and new technologies remains the best way to durably encode learning.

2024 Highlights

01A Simple Study Guide Yields Big Results

Even mature students trying to master material they’ve just learned often rely on faulty tools—or no tools at all. In fact, a 2024 study finds that many undergraduates approach academic work completely “unaware of which learning techniques are effective.”

In search of a simple intervention, a researcher provided psychology students with a basic, 2-page guide on evidence-based study strategies. Bullet points explained how students could “remember more of the course material” by testing themselves and answering from memory, instead of rereading—and cautioned them to double-check their answers for accuracy and spread their study time over a number of days. Students who received the guide saw their chances of receiving a high grade in the course improve by 24%, compared to their guide-less peers.

Making a dent in study habits is easier said than done. Consider taking the approach a step further: Regularly quiz students on optimal study strategies, asking them to describe and defend their plan of attack for a coming test, for example, while citing evidence backed by the science of learning.

02Yet Another Risk of ‘Learning Styles’

When the concept of learning styles first became popular in the 1970s, educators saw it as a simple way to differentiate their teaching. By the 2000s, though, the idea had come under fierce attack: Experimental researchers were unable to find a shred of credible evidence that students perform better when instruction is tailored to their “preferred mode” of learning.

An October 2023 study opens another line of criticism, concluding that learning styles may also lead educators to a species of academic profiling. Teachers and parents rated “visual learners” as more intelligent and “hands-on learners” more athletic by wide margins—and the researchers found that similar misconceptions, like “chemists and engineers are often kinesthetic learners,” are sometimes perpetuated in teaching colleges.

Learning styles remain one of the more pernicious myths in education. They offer no measurable short-term benefits and, according to the latest research, exact a long-term toll by warping how teachers, parents, and even peers view students’ potential.

03The Hidden Cost of Schools in Disrepair

That old HVAC system in your school does more than just expel warm air. According to a 2024 study that analyzed data from over 10,000 districts in 29 states, spending on school infrastructure can lead to dramatic increases in academic achievement, especially for low-income students.

The researchers concluded that targeted investments in school improvement projects raised test scores and could close as much as 25% of the achievement gap between lower- and higher-income districts: “Investments in school infrastructure such as HVAC, safety and health, plumbing, roofs, and furnaces produce large increases in test scores, likely because they improve students’ learning experiences.”

Adequate funding for schools can lift all boats, but your priorities matter, said researcher Barbara Biasi. Spending on athletic facilities improves the price of local housing but doesn’t budge test scores; spending on plumbing and HVAC has no effect on housing prices—but improves academic outcomes. Choose wisely.

04A Thumbs Up to Finger Counting

It’s natural for young mathematicians to count on their fingers while performing simple calculations. But is finger counting helpful or a hindrance?

In a 2024 study involving over 240 first graders, half were assigned to a math class that integrated explicit instruction in finger counting, like how to use your fingers to represent numbers and solve simple addition and subtraction problems. At the end of the year, and on a follow-up test 9 months later, the finger counting group performed significantly better on tests of addition and subtraction than their peers.

Incorporating the use of fingers in primary math “may facilitate the acquisition of numerical and arithmetical skills,” the researchers conclude. Fingers, in fact, may be particularly useful for grasping the properties of whole numbers because the brain has an area dedicated to each finger on the hand.

As math gets more complex, students need to move past finger counting—but early mastery of the method “may facilitate a shift to mental strategies that no longer require overt actions,” the researchers note.