The Power of Multimodal Learning (in 5 Charts)

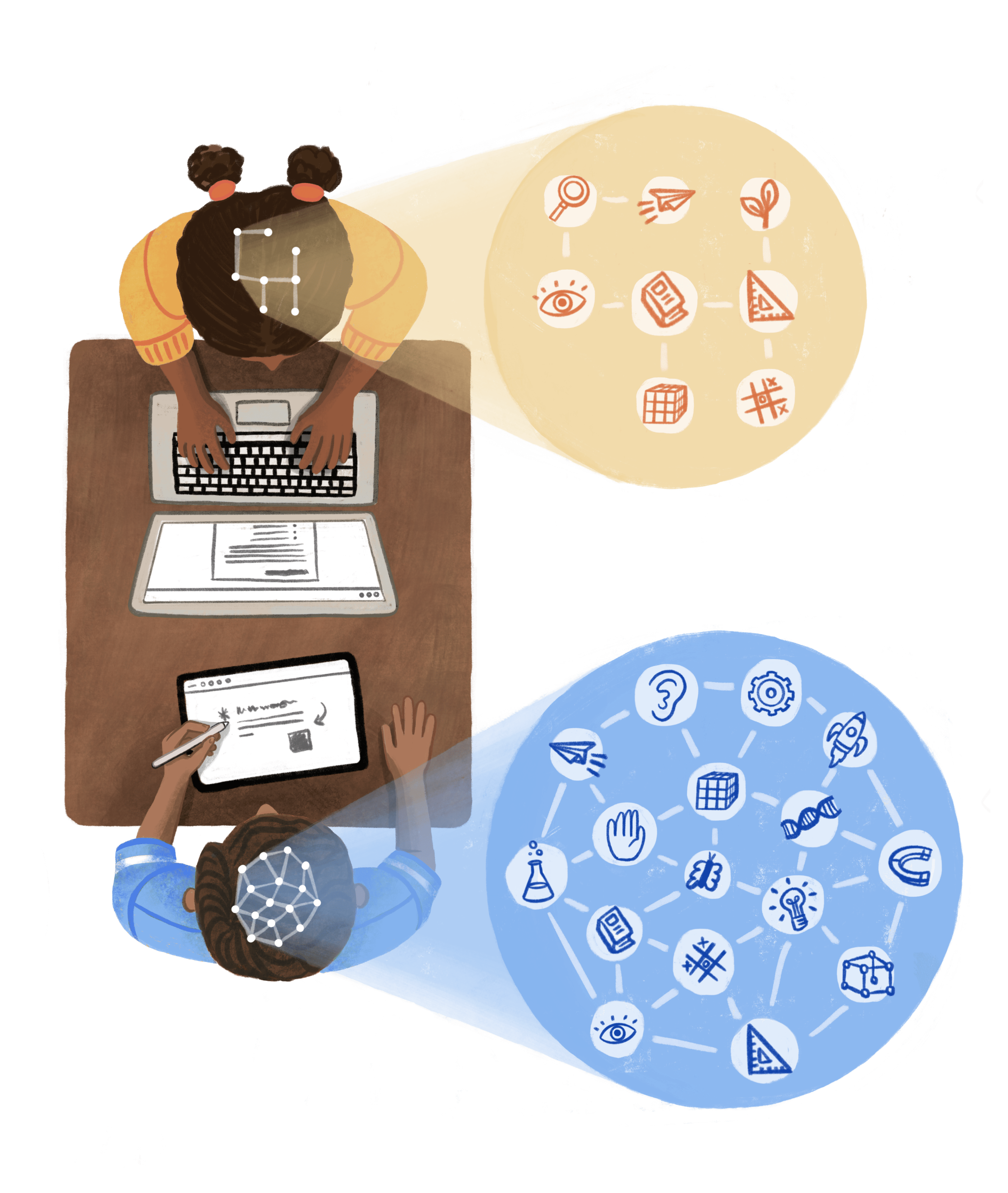

When students engage multiple senses to learn—drawing or acting out a concept, for example—they’re more likely to remember and develop a deeper understanding of the material, a large body of research shows.

Your content has been saved!

Go to My Saved Content.It might seem like a scene from a wildlife documentary, but turning students loose to stride and hop around the classroom pretending to be lions, and then gazelles, is a powerful lesson on the differences between predators and prey. A growing number of studies reveal the neural underpinning of what researchers call “embodied learning” or “multimodal learning”—using your body to encode material more deeply by drawing, singing, or dancing, for example—and provide a window into how and why the approach works so well.

“When students learn through multiple senses, their brains create stronger, more integrated memories,” explains Brian Mathias, a neuroscientist at the University of Aberdeen. In a comprehensive 2023 study co-authored with Katharina von Kriegstein, they demonstrate that information encoded via multiple routes—by putting pen to paper to sketch the parts of a flower, for example, in addition to labeling the diagram—establishes a richer web of connections, and taps into “the wealth of information that is available in more naturalistic settings, where learners have at their disposal an abundance of sights, sounds, odors, tastes, and proprioceptive information.”

On the surface, it may seem like fun and games, but there’s a lot happening under the hood—and the practice is highly effective. In a 2020 study, Mathias and his colleagues discovered that 8-year-old students learning a new language had 73 percent better recall if they used their hands and bodies to mimic the words—pretending to be a plane while learning the German word “flugzeug,” for example. Meanwhile, a 2022 meta-analysis encompassing 183 studies concluded that pairing words with actions—bodily recreating the motion of the earth, moon, and sun when learning what an “eclipse” is, for example—is a “reliable and effective mnemonic tool” with an effect size of 1.23, well above the 0.8 threshold for a “large” impact. Educators should lean on the “multi” in multimodal: “As a rule of thumb, the more modalities implicated, the better memory will be,” the researchers conclude.

Here are a few, powerful multi-sensory strategies that integrate the material being learned with a corresponding physical activity, along with a look at the intricate cognitive mechanisms at play.

A Hands-on Approach to Learning Fractions

A simple tweak to a basketball court helps kids grasp the relationship between parts and wholes.

What do you get if you add ⅓ of a cookie to ¾ of one? Kids are often puzzled when confronted by fractions—a stumbling block that often extends into adulthood—but a new study suggests that a twist on playing basketball can help demystify the relationship between parts and wholes.

In the study, which encompassed more than 200 4th- through 6th-grade students, researchers made simple adjustments to a basketball court, drawing 1/4, 2/4, 3/4, and 4/4 along one side of the court, with their corresponding decimal values on the other side. As players made a shot, the rebounder would yell its point value while a scorekeeper tallied the score on a number line. Students also endured mini-challenges, such as trying to complete shots as quickly as possible to get to 1.5 points, boosting their ability to understand the relationship between ¾ and 0.75, for example.

While their desk-bound peers didn’t see much improvement in math skills—seeing only a 1 percent improvement in adding fractions and decimals, for example—the physically active kids saw improvements between 8 to 30 percent in their ability to work with fractions and decimals, slam-dunking their peers on the ability to add and convert between the two.

This low-cost activity—you can draw on an existing court with chalk or move the game indoors with crumpled paper and waste baskets—is a replicable strategy that’s “playful, engaging, embodied, physically active, and rooted in cognitive science research.”

Tapping Into the Power of Sketchnotes and Concept Maps

Abstract mental models are reinforced—and can stand the test of time—when they are doubly encoded through visual and tactile sensory networks.

Unlike passive activities such as listening to a lecture or viewing images, drawing is an active process that requires students to reconstruct material. The sensory fusion of tactile information transmitted from the fingers and hands and perceptual information processed in the visual cortex strengthens the cognitive pathways that lead to durable, deeply encoded memories.

The benefits of drawing aren’t limited to basic representations, though—more sophisticated diagrams such as sketchnotes and concept maps can also facilitate deeper comprehension, research suggests.

While a good starting point is to ask students to create simple sketches—a diagram of the parts of a flower, for example—such depictions “lack features to make generalizations or inferences based on that information,” researchers explain in a 2022 study. To give students a clearer sense of the big picture and tackle conceptual abstractions, incorporate those initial drawings into larger-scale, organizational illustrations—the water cycle, for example—linking concepts with arrows, annotations, and other relational markings. In the study, fifth grade students who created organizational drawings outperformed their peers who drew simpler representations by over 350 percent on tests of higher-order thinking.

When trying to maximize retention and comprehension, start by giving students paper and pencils and encourage them to draw the material, then move them up to sketchnotes and concept maps as they make connections—both mental and physical—between ideas.

Finding Your Voice

You can power-up critical, cross-disciplinary skills like reading by producing speech as you read along visually.

It’s a technique that actors and actresses swear by, and it can be easily adapted into your classroom. In a 2018 study, researchers called reading aloud a “versatile but flexible learning strategy” that produces a unique blend of visually scanned words and “distinctive speech information” that “stands out.”

The researchers split college students into several groups and asked them to read silently, listen to recordings of spoken words, or to read aloud to themselves. “There was a gradient of memory” across the conditions, the researchers found: While 77 percent of words read aloud were remembered, only 65 percent of silently read words stuck. Layering vocal production atop reading can also improve writing skills. In a 2022 study, students who proofread materials aloud spotted 12 percent more hard-to-catch errors—such as the nefarious they’re/their/there mistake—than those who read silently.

Reading is a common activity across academic disciplines, multiplying the benefits of even small improvements. Consider pairing kids together to “read sections of the text aloud to each other (partner reading) and then discuss and answer your questions,” suggests literacy expert Timothy Shanahan. Research also shows that choral reading—teachers and students scanning along as they read text out loud in unison—can improve reading fluency and vocabulary while increasing students’ confidence. At Concourse Village Elementary School in the Bronx, for example, choral reading is embedded in all disciplines, from art to math and science, to “demystify the often-opaque process of analysis in a shared, safe space before trying it on their own.”

Learning ABCs With Whole-Body Movement

The more of the body used to reinforce the material, the deeper the learning.

When our youngest students use their whole bodies to learn their ABCs—moving like a snake as they hiss the sibilant “sss” sound, for example, or reaching for the sky as they say and mimic a Y—they’re likely to comprehend letter-sound pairs more deeply, a 2022 study found.

Five- and 6-year-olds in Denmark spent eight weeks learning “letter-sound couplings and word decoding” under the watchful eye of researchers. The resulting study concluded that whole-body movement improved the students’ ability to recall letter-sound pairings by 34 percent, and nearly doubled their ability to recognize hard-to-learn sounds—such as the difference between the sounds c makes in “cat” and “sauce”—when compared to students who simply wrote and spoke letter-sound pairings at their desks, or used their hands to mimic the letters.

That’s a big difference for a life-changing skill, and the more of their body kids use, the better. Educators should “incorporate movement-based teaching” into their curricula, and give special consideration to “whole-body movement,” the researchers asserted.

Why Writing Beats Typing

Brain scans reveal that the fine-motor skills involved in writing by hand light up parts of the brain associated with deeper learning.

For kids learning new material, typing doesn’t seem to do the trick.

In 2012, brain scans of preliterate children revealed crucial reading circuitry flickering to life when kids hand-printed letters and then tried to read them. The effect largely disappeared when the letters were typed or traced. More recently, in 2020, a team of researchers studied older children—seventh graders—while they handwrote, drew, and typed words, and concluded that handwriting and drawing produced telltale neural tracings indicative of deeper learning.

“Whenever self-generated movements are included as a learning strategy, more of the brain gets stimulated,” the researchers explain. It appears that keyboard typing—which invokes less “kinesthetic information” than the “fine and precisely-controlled hand movements” required for cursive writing or sketching—fails to engage brain networks as productively.

FMRI and other neuroimaging technologies offer the clearest glimpse of the mechanisms underlying multimodal learning, and the resulting brain scans are persuasive arguments for policies like mandatory cursive instruction.

But it would be a mistake to replace typing with handwriting or drawing entirely; there are other pressing issues to consider. In the modern era, all kids need to develop digital skills, and there’s evidence that technology helps children with dyslexia to overcome obstacles like slow note-taking or illegible handwriting, ultimately freeing them to “use their time for all the things in which they are gifted,” says the Yale Center for Dyslexia and Creativity.

All graphics by Meaghan Barry.