How to Broaden Students’ Sense of History

By incorporating diverse voices not found in some textbooks, teachers can provide a fuller, more accurate picture of historical events.

Your content has been saved!

Go to My Saved Content.They say that history is written by the victors. Unfortunately, history as told by the victors is not a complete story. For far too long, people have accepted the standard narrative as the whole story. In order to tell more of the story, we need to include more diverse and authentic voices. These perspectives supplement the story and broaden students’ understanding of history.

Why integrate diverse voices? Doing so is an effective way to expand the narrative in the classroom. It promotes tolerance and understanding while providing validation and inspiration to people who historically have been marginalized. Students need to see themselves in history, and they also need to see others’ perspectives. Diverse voices inform students about values, achievements, and struggles of people other than themselves. Lastly, today’s history is influenced by past events. A more inclusive history helps us to better understand the world we live in.

How to Integrate Diverse Voices

Letting people tell their own stories is my main motivation behind integrating diverse voices in the classroom. To achieve this goal, I have hosted Holocaust survivors and World War II veterans in my classroom. A textbook account pales in comparison with a first-person account of the realities of war. Contact your local VFW chapter, local history museum, or Holocaust remembrance organization to find speakers for your classroom. During distance learning, it may be possible to host these speakers virtually.

When speaker visits are not possible, oral history accounts are a great alternative. The poor treatment of African American veterans after World War II is usually covered in a sentence or two in textbooks. Compare Mary Crawford Ragland, a member of the 6888th Central Postal Directory Battalion, talking about discrimination she faced while looking for a job after the war with the typical lines in a textbook that might suggest that “African American veterans came home to an unfriendly society.” Her story of being offered a job interview and then having it withdrawn after the employer saw her complexion is a powerful message for students to hear. This is a sentiment I could never adequately convey, let alone express as well as she does.

There are many sources of oral history interviews available online, which is especially useful in times of remote learning. Consider the Library of Congress’s Veterans History Project and the New York Public Library’s Community Oral History Project. The Southern Oral History Program allows users to search by subject matter, job, or ethnicity. The National Japanese American Historical Society website contains interviews with survivors of an internment camp. The United States Holocaust Memorial Museum provides a database of oral history interviews, many of which are available for online viewing.

Incorporating Literature

Another way to include diverse voices is to integrate literature written by and/or from the point of view of marginalized people.

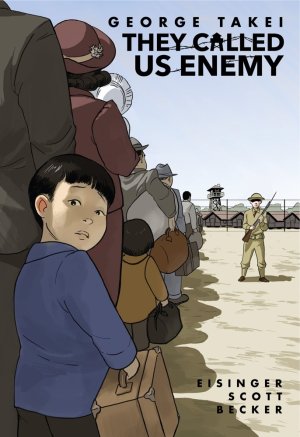

They Called Us Enemy is a powerful graphic novel that illustrates the story of George Takei’s childhood in an internment camp and gives the reader a firsthand view of the Japanese American experience of World War II. Takei illustrates the struggle of families that were given 10 days to liquidate their livelihoods before all of their assets were frozen by the United States government. Later, he highlights the governmental survey that sparked conflict among internees over joining the army of the country that had brutally betrayed them.

Uprising, by Margaret Peterson Haddix, presents labor history from different angles: A society girl’s experience is contrasted with that of immigrant laborers in the Triangle Shirtwaist factory. Labor history is not usually told from the point of view of labor—especially young immigrant girls. This book exposes struggle, quality of life, living conditions, and motivations. Students can see how multiple versions of history can coexist.

Code Talker, by Joseph Bruchac, discusses the importance of Native American code talkers in World War II while highlighting how they were otherwise disregarded by society. The contrast between the main character’s bravery as a Marine during the war and the lack of respect that Native Americans received off the battlefield before and after the war is striking. In addition, the author exposes students to Navajo history, culture, and traditions.

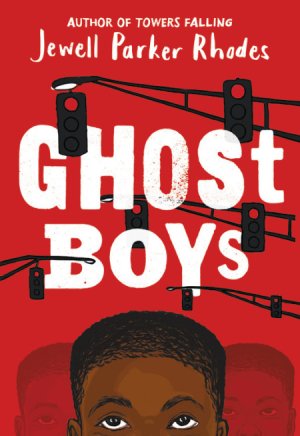

Ghost Boys, by Jewell Parker Rhodes, is especially effective because it allows students to connect the murder of Emmett Till to current events. It tells the story of the shooting of Jerome, a young African American boy, by police as he is guided through the aftermath of the shooting by the ghost of Emmett Till. It’s told from the point of view of Jerome as well as the daughter of the police officer.

Other Words for Home, by Jasmine Warga, tells the story of Jude, a young immigrant girl from war-torn Syria navigating her new Cincinnati home while trying to make sense of her identity as a teenager, a Muslim, and a Middle Easterner, a term that is new to her. She navigates bias, prejudice, and culture shock while worrying about her brother in Aleppo. This book helps nonimmigrant students understand the American immigrant experience and build empathy and understanding by reading about the effects of prejudicial words and actions.

History is incomplete if it does not include multiple authentic viewpoints of those who lived it. Integrating these diverse voices into our teaching of history through in-person or virtual visits, oral histories, and literature helps enrich the teaching of history by adding a depth that is often sorely lacking in textbooks.