Lacking Training, Teachers Develop Their Own SEL Solutions

A new survey by Education Week Research Center shows nearly half of teachers feel their schools do not have adequate support for their students’ social and emotional needs.

Your content has been saved!

Go to My Saved Content.The few workshops she attended on social and emotional learning left Arizona kindergarten teacher Ashley Toscas ill-prepared to help her students manage their emotions, writes Sarah Schwartz in “Teachers Support Social-Emotional Learning, But Say Students in Distress Strain Their Skills.

"There are so many students with so many mental-health needs, I [felt like I] needed a separate degree," Toscas told Schwartz, referencing her students’ poverty and trauma.

Toscas isn’t alone, according to Schwartz’s article, which recaps Education Week Research Center’s nationwide survey that found nearly half of teachers surveyed felt they their schools did not have adequate staff on hand to support their students’ social and emotional needs—and as result, were left to intervene on their own but without the appropriate resources to do so.

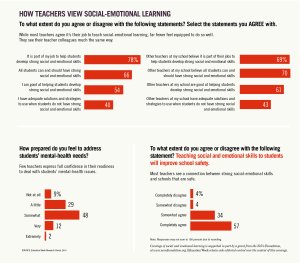

Even if the necessary support exists, teachers don’t feel they have received enough training—either through teacher preparation programs or professional development opportunities—to address student needs. Only 40 percent of those surveyed said they have “adequate solutions and strategies to use when students don’t have strong social and emotional skills.” Meanwhile, fewer than 15 percent of those surveyed said they felt “very” or “extremely” prepared to address student mental health needs.

Though national awareness of the value of social and emotional learning has increased, the survey suggests social and emotional training for teachers may be implemented half-heartedly in some districts or as an “add-on” for teachers who already struggle to fit everything into a busy day.

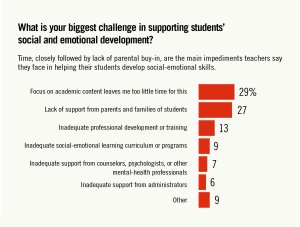

According to nearly a third of respondents, the pressure created by academic goals didn’t leave enough time to focus on SEL, while 27 percent of teachers surveyed cited “lack of support from family or parents” as the main obstacle to social-emotional support. For others who had received training, a number reported its lack of relevance, specifically that the training tended to focus more on establishing routines than how to handle students’ behavior in real-time situations.

Toscas developed some of her own classroom remedies, like looking for nonverbal signs in students’ body language as an indicator that a student might need some one-on-time with her or quiet space alone to decompress, Schwartz writes. These homegrown solutions are fairly common among educators, according to the survey, which found that in the absence of trained assistance, teachers create their own responses to students in distress. “Seventy percent of teachers said they addressed their students' mental-health challenges by talking with them,” Schwartz notes.