Making Project-Based Learning Inclusive in a Hybrid Setting

It’s not easy to help students feel connected when everyone isn’t in the same room, but these science teachers found a way to make it work.

Your content has been saved!

Go to My Saved Content.Moving to hybrid classrooms creates an even greater challenge for building community. In hybrid classrooms, some students never see each other in person, and some students never see their teachers in person. Project-based learning provides a powerful vehicle for creating a shared learning space, one that makes it clear that all students’ voices are needed and welcome in the classroom. Being flexible and welcoming about how kids choose to participate builds trust as the kids feel valued, welcomed, and accepted.

Students get the opportunity to share parts of themselves through the questions they ask, investigations they design and carry out, and artifacts they develop and present. The more of themselves the students share, the more connections are built.

Here are four strategies to build trust using project-based learning.

Use Students’ Questions to Strengthen Relationships

Teachers build relationships by ensuring that all students—face-to-face and virtual—generate questions about things they’re interested in. This not only encourages participation but also is a low-stress way to help students articulate what they know.

Science co-teachers Susan Zaemish and Tim Reiser hold a genius hour each week in their hybrid classroom. Students select a question that they want to learn about and study. They then research their answers and share their findings in breakout groups, in which half of the students are in person and half are online. Students look forward to having an audience and learning about each other.

When students ask questions, they also share something about their experiences, how they view the world, and what is important to them. Examine questions with that lens to get your students to share more.

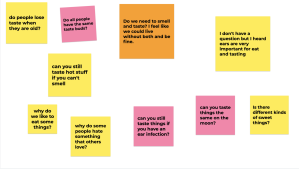

It’s helpful to give students a choice not only in what questions they ask but also with how they’re presented. Monique Coulman, a fourth- and fifth-grade teacher, lets her students, whether in person or online, have a choice in communication method: voiced, chat, sticky notes, notebook, voice recording, or typing in the Google doc.

Amy Lazarowicz, a math and science teacher, accomplishes a similar goal by using “chat blast” for students to share their questions. Each student takes the time they need to write a question, and then Lazarowicz publishes all of her class’s questions at the same time. The goal is to give all of her students time to generate valuable questions without worrying about who answers first. When students generate questions and see those questions become integrated as classroom thinking tools, they feel welcomed as part of the classroom community.

Enhance Social Connections Between School- and Home-Based Students

Students who are remote can feel left out of hybrid classrooms. To address this, Susan Zaemish pairs a virtual student with an in-person student, so that one part of the pair is always in the classroom. The students in the classroom handle the materials during the ongoing investigation or building of an artifact, so each day one student is manipulating the design. The virtual students describe and rationalize the changes and decisions they made the previous day and add suggestions for revision. Both partners have to use reasoning to convince their counterpart.

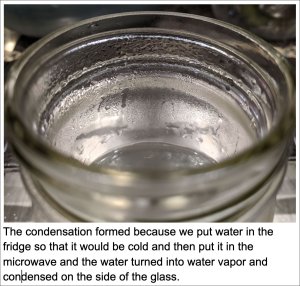

To include remote students in hands-on activities, Zaemish asks partners to collaborate using home materials. For example, when her students were trying to figure out a way to get water to condense (as a model for precipitation), the student at home heated a cup of water in the microwave and then covered the top with ice. Both students watched for condensation.

Consider Ways to Give Virtual Students a Say in Planning Activities

Fourth-grade science teacher Jodi Sturk displays a makeshift windmill on the Zoom screen. She then invites her students to share ideas they have about investigating energy. As students write in the chat, she follows their suggestions only if they can provide a prediction and rationale: “Bring the windmill closer—I think there will be more energy and the cup will move up faster,” or “Closer won’t make it move faster—it is still the same amount of energy! You have to turn the fan on high.” As each student has equal sway in the carrying out of the investigation, all feel their ideas are valued, and they develop common purpose.

Use Apps That Allow Students With Slow Connectivity to Present Artifacts

In our classrooms, we celebrate what students have learned through artifacts—representations of what they learned during the unit. Even when students are not present in the same physical space, or if they have slow connectivity, they can still create presentations that reflect their learning journey.

To solve issues of community related to connectivity, fourth-grade teacher Mary Modaff uses Seesaw for presentations. Seesaw allows all students to practice, record their video, and then present their artifact one by one to the class. As the students present, they can stop the video to explain what they’re doing. Modaff’s students with internet issues, shy students, and those who speak multiple languages appreciate being able to use prerecorded video for public speaking.

One of her students worked at home on a presentation slide that showed how a fossil of a saltwater fish can end up at the top of a mountain. The student videotaped the physical model and recorded her voice explaining the model. She was virtual and had bad connectivity, so instead of presenting live, she wrote a short introduction in chat: “I think I know how the land features got that way. Watch.” Then her animated model displayed her thinking without internet interference.

The class community asked probing questions, especially about her recorded explanation. They asked, “Why would the ocean water evaporate and leave one fish?” The questioning, coupled with the request for more evidence and reasoning, caused her to rethink her initial model. It also made her feel that her ideas were valued and that she was included in the class community.

Students can feel left out when they struggle to be part of a discussion due to connectivity issues. Leveraging different ways to present ideas in a shared format makes every student feel like they’re part of the community.