Responding to Disruptive Students

Negative attention doesn’t help difficult students change their ways, but teachers can alter classroom dynamics through this exercise.

Your content has been saved!

Go to My Saved Content.Negative attention, or punitive communication, is a common, unconscious habit of defense when a familiar environment feels unsafe or unmanageable. Educators may turn to it instinctively when they feel frustrated because they see their work being disrupted. But difficult students don’t benefit from being punished.

Generally, guidance about challenging behavior at school targets the challenging students. I’d like to break this unidirectional point of view and approach the topic by looking at the educator. I want educators to feel physically and emotionally safe in class always. And I want empathic educators who are confident and prepared for their response toward challenging behavior—their own included.

“Behavior is communication. Behavior has a function. Behavior occurs in patterns,” Nancy Rappaport and Jessica Minahan write in The Behavior Code: A Practical Guide to Understanding and Teaching the Most Challenging Students.

Unfortunately, the same is true of negative attention. Negative attention communicates that an educator doesn’t know any other language to access the relationship with a student. Negative attention’s function is self-protective and unconsciously anti-inclusive. Negative attention’s pattern sounds loud and looks clumsy.

“The only behavior teachers can control is their own,” Rappaport and Minahan advise. What follows is an idea that can help teachers change their responses to challenging, disruptive behavior.

Mapping Behavior

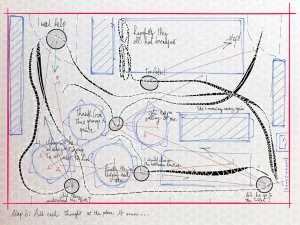

Draw a map of your classroom, including doors, windows, desks, blackboards—all significant items and areas. I’m sure you’ve already got a clear idea of where the most challenging students usually sit. Now imagine teaching class on a regular day. Trace the paths you usually take across the room. Do you sometimes speed up for a particular reason? Draw a bold line on the map wherever you usually hurry your pace.

Draw a circle on the line to mark each stop you make on your journey. From each circle, draw a line with another color to represent your initial glance from that position. Who or what are you looking at? Continue drawing lines to match every glance you can remember being part of your everyday “watching” routine. If you prefer to teach sitting down, begin your map by tracing the lines of your glances from the place where you usually sit.

If you raise your voice, draw arrows tracing the direction and target of each instance.

Now put your breathing on the map. Are you conscious of the way you breathe during class? Use a new color and draw a wavy line on top of the lines and arrows you’ve already sketched. Does the wavy line look even, or have you drawn some chaotic or nervous zigzags? Could it be that you’ve sometimes forgotten to breathe? Use the same color to draw a flat line for such moments.

Can you remember a frequent thought you have during class? Does it concern all of your students, or some student in particular? Write your recurrent thought on the map close to that student’s desk. Repeat this for every student for whom you have a specific thought. Do your thoughts refer to yourself? Write them down on the map at the spot where each one comes to mind. Do the same if your thoughts relate to the class as a whole.

This map enables you to view yourself during class, to track your emotional and physical data, and to evaluate your behavior, including outbreaks of negative attention.

The map will help you to understand the context, form, and time frame in which negative attention might emerge, because you can see when and where you feel insecure or unsafe. You have now begun to visualize yourself within a classroom, conscious of the surrounding objects and interacting students. Through the map, you might discover you are too often at the center of attention.

Since attention seeking is also a very common example of student behavior, and negative attention an inadequate response to it, it’s time to observe your students.

The Disappearing Teacher

Look at your map and find the best observation spot in the classroom, where you can watch students at work without intervening. Then set a task you know your students enjoy doing, and disappear. Just enjoy observing your students as the protagonists of their own learning.

During this experiment, you shouldn’t leave your observation post and really must remain silent. The goal is to create a situation in which you expressly avoid whatever negative attention you usually give—verbal or physical—and comprehend your students’ needs more fully.

Repeat this experiment several times, until you find the best spot to observe every student. This step is essential to discovering any changes in how you and your body have unconsciously expressed negative attention in the past.

Many educators who have done this experiment report significant gains in achieving authentic, positive sovereignty in class. They also calmly accept that no lesson goes as expected.

Investing time in building physical and emotional familiarity with the learning environment, instead of nervously anticipating disruption, changes the educator’s perspective toward the whole class, their interaction with individual students, and their self-awareness. Negative attention stops being a solution—instead it is seen as a hindrance to the process of understanding students’ needs.