A Strategy for Overcoming Equity Issues in Gifted Programs

Universal screening, some school districts say, makes access to gifted education more fair—but costs can be high.

Your content has been saved!

Go to My Saved Content.New data from Memphis, Tennessee, confirms that when schools use traditional teacher-referral models to identify gifted kids, a lot of gifted children who are poor or of color slip below the radar and never reap the program’s benefits, writes Laura Faith Kebede for Chalkbeat.

But Shelby County Schools, the district that includes Memphis, is taking direct aim at the old model’s inequities—the “secret handshake” that allows rich, and predominantly white, parents to navigate the system and place their kids in advanced programs—by switching to a universal screening process that attempts to level the playing field. The results have been impressive, more than doubling the number of students identified as gifted last year: 600 kindergarten through second-grade students are now entering the district’s gifted program, known as CLUE—an acronym for Creative Learning in a Unique Environment—and another 600 third- through eighth-grade students are in line to test into the program.

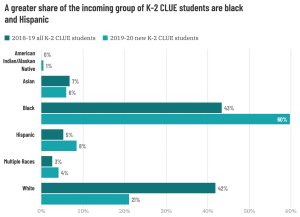

As a result of the switch to universal screening, “more black students are represented in the program’s newest K-2 cohort,” Kebede writes. ”About 60 percent of newly identified elementary CLUE students are black, compared with last year’s 44 percent. Officials hope eventually the CLUE program can be more representative of the district’s racial makeup—nearly three-fourths of its students are black.”

Nationwide, approximately 13 percent of elementary students from high-income families are enrolled in gifted programs, compared to just 2 percent of students from low-income families, according to a recent study from Vanderbilt University’s Peabody College and the University of Florida’s College of Education. “In other words, the most affluent students are six times more likely than the least affluent to be identified as gifted,” the study’s authors write in a blog for Harvard Education Publishing. These and other findings underscore that unequal access to gifted programs among low-income students is not solely due to school policies or whether a school offers a gifted program. Instead, the authors conclude, “We suspect that access differences arise from whether low- and high-[socioeconomic status] students are referred for evaluation by their teachers or parents, or perhaps from biases in gifted-evaluation instruments.”

Gifted education comes in many forms across the United States. This is because federal law, while acknowledging that gifted students have unique learning needs that local schools aren’t usually equipped to address, doesn’t otherwise offer specific provisions or defined requirements for meeting these needs. Especially for low-income students, English language learners, and students with disabilities, that translates to a great variation in the quality of and access to gifted programs.

New York City, for example, which has 1.1 million students enrolled in its public schools, is grappling with how to create a more equitable school system, and part of this effort concerns the city’s gifted and talented program. While 66 percent of students enrolled in public schools citywide are black or Hispanic and mostly low-income, only 21 percent of students in the city’s gifted program are students of color. Last year, a panel appointed by the mayor recommended doing away with the program entirely, a contentious proposal that set off a prolonged and still unresolved battle among the many stakeholders in the city’s school system.

Pedro Noguera, a renowned professor of education at UCLA’s Graduate School of Education weighed in on the matter via Twitter: “Instead of eliminating gifted programs, New York City should expand them,” he wrote, expressing a widely held belief among the dissenters. “All kids deserve access to a challenging education. Too often we confuse privilege with giftedness. New York has a chance to change this.”

In Shelby County, district leaders are hoping that by implementing universal screening and investing in the expansion of its gifted program, the CLUE program will create a more diverse group of students “ready to take high school courses that award college credit, which would better prepare students for college-level work.”

So far, the district pays for the CLUE program for kindergarten through second grade and the state pays for the third- through ninth-grade program. “The switch did not cost the district anything this year because officials used tests they already had access to, but the district plans to hire more CLUE teachers next year,” Kebede writes. But the cost can be prohibitive. In nearby Nashville, for example, the district “piloted a universal screening for second graders in 2017, but dropped it because it was too expensive.”