A Strategy for Guiding Students to Take Deep Notes

Moving away from a traditional method of taking notes can help students truly focus on the main learning objectives of a lesson.

Your content has been saved!

Go to My Saved Content.Are your students scribbling furiously during lessons, only to stare blankly at their notebooks when it’s time to review? It’s a common struggle: Traditional note-taking often leaves students with pages of unprocessed information. Let’s rethink this skill with a simple, research-backed approach that helps capture the essence of lessons, make connections, and retain information more effectively.

UpgraDE to Deep Notes

Traditional note-taking leads to a lesson that washes over students as they transcribe lectures without processing information. This approach is like highlighting every word in a textbook—nothing ends up standing out. Slowing down and focusing on key information shifts notes from superficial to deep.

Deep notes aren’t about capturing every word spoken in a lecture. They focus on distilling the most essential ideas. The process of creating them involves actively engaging with the material, summarizing, asking questions, and making connections.

I used to furiously scribble notes at a professional learning session, only to later realize I couldn’t recall anything that was said. That’s the downfall of transcript-style notes. Our brains simply can’t remember everything we heard if we simultaneously write it all down. Instead, we can focus on capturing the essence of what matters most—this is what we call deep notes.

SET Students UP FOR SUCCESS

Imagine teaching a great science lesson about space and feeling confident in how you presented it. The next day, you learn that your students’ only takeaway was a joke about a “space party” (we need to “planet”). That joke stuck because it triggered a dopamine boost, marking it in their brains as important. As designers of learning, we can intentionally use this note-taking strategy to signal what’s important and purposefully build in learning experiences that give students’ minds dopamine boosts.

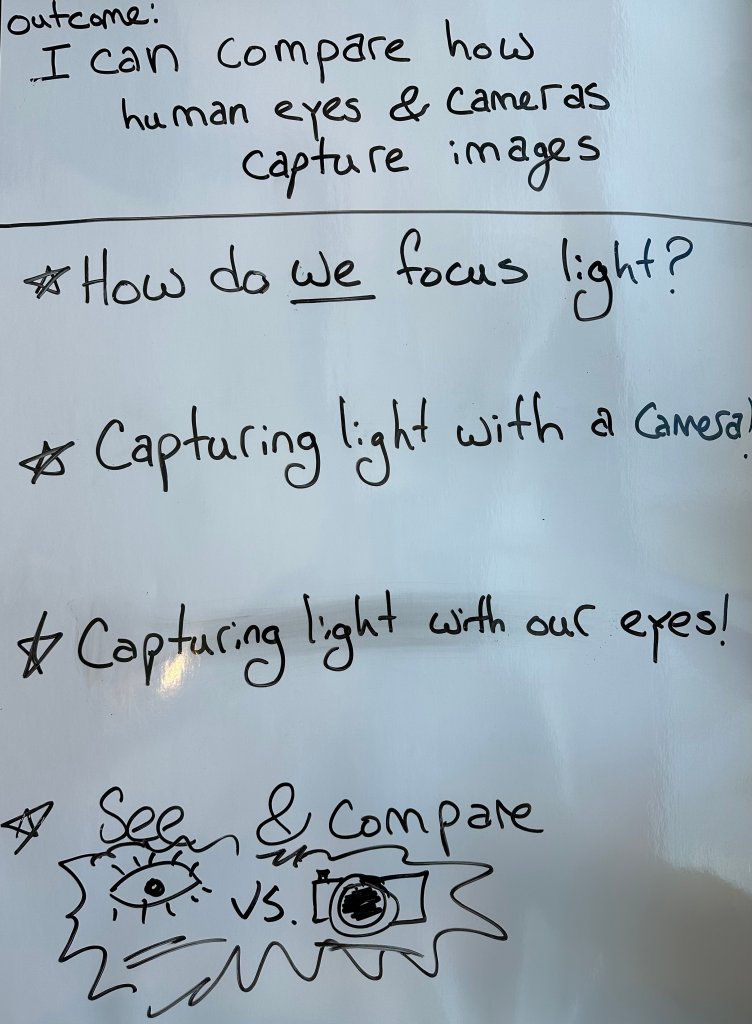

Here’s what that science class could have looked like. We start by sharing the learning objective, “Understand the commonalities between terrestrial planets.” By bringing attention to the objective at the start of the lesson, we’re priming students’ brains for making connections to the essential material. We then highlight the objective by writing it clearly at the top of the lesson parking lot—a chart paper or prominent spot on a whiteboard where we signal to students the key learning to take away.

CREATE The Notes Parking Lot

Let the lesson begin! With the lesson parking lot in place, we can have students put away their notebooks and become active participants in the lesson. By shifting note-taking to the end of the lesson, we are preventing students from writing surface-level notes and helping them focus on one task—learning.

Our lesson might include a lecture, hands-on activities, or a progression of engaging questions for discussion. The style of the lesson won’t affect the routine; instead, when we cover the crucial topics in the lesson, it’s essential that we add these topic titles to our learning parking lot. For example, we might start our space lesson by adding Mercury to the parking lot under the learning outcome. When we move to our next topic, Venus, we add it to the list.

By the end of the lesson, we will have added three to five topics to the learning parking lot.

These are themes and big ideas that we want to draw students’ attention to during the lesson and that they’ll write their notes about at the end of the lesson. While we might plan for and select these topics before class starts, I like to allow the categories to emerge organically, by taking cues from students’ questions and comments. This way, the pace of the lesson is naturally generated by student engagement. For example, if we started digging into the unique characteristics of Mercury, the topics might shift to “solid surface,” “density,” and “core,” instead of looking at different planets as I had planned.

FOCUS ON Collaboration TO Support Recall and Transference

At the lesson’s end, have students form small groups to cocreate their notes on chart paper or whiteboards. They’ll discuss, draw, and write key concepts, moving from superficial to deep understanding. Students love sharing their ideas, and this collaborative process reinforces learning. Students that I have done this with (from third to ninth grade) have told me that they loved talking about what was important to them and how “it is so great that everyone gets to share their ideas—unlike normal class.”

Neuroscience tells us that spaced retrieval and recall of information are key to the learning process. While students are creating their notes, we are designing the opportunity to actively think about the material, compared with letting the lesson simply wash over them. The beauty of this routine is what happens next.

Once they are completed, we take pictures of each group’s notes and share them digitally in Google Classroom (Microsoft Teams’ Class and One Note are other good options). Now, students have a resource bank, and we have multiple opportunities to foster recall. Here are some examples for other lessons:

- Have students create video summaries explaining and making personal connections to another group’s notes.

- Use the notes from a few classes to create a Venn diagram of key information (such as comparing terrestrial and gaseous planets).

- Gamify the lesson with summarization challenges, scavenger hunts, and trivia competitions.

Finally, we use the group notes to make connections between other units (generalists in elementary grades can even make connections between subjects), which allows transference. For example, in a math class, we might use the notes to help calculate the volume of planets or the time for sunlight to reach each planet.

By including this interactive routine, students leave class primed to make connections to the material. Because they were fully engaged during class and spent time reflecting on the topics to cocreate deep notes at the end of class, we help their brains start to make important neural networks, and when we bring back and meaningfully use their notes, they are telling their brains, “This material matters to me.”