Cultivating Writing Skills in Young Learners

This strategy for teaching creative writing to first- and second-grade students uses an engaging and differentiated approach.

Your content has been saved!

Go to My Saved Content.Teaching writing in the elementary grades comes with its own set of challenges: helping students plan their writing, organizing materials, providing appropriate drafting tools, differentiating instruction to a wide range of abilities, and ensuring that publishing is manageable for young learners.

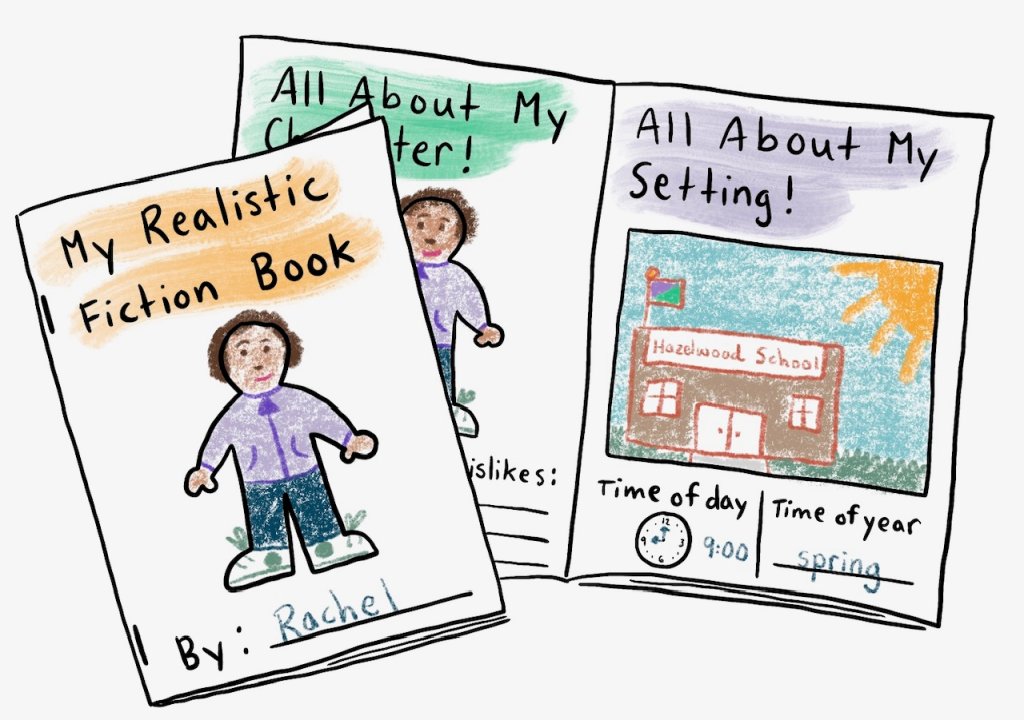

To better overcome these obstacles, I’ve developed a simple but effective solution: DIY booklets. These custom-made, stapled booklets compile all the materials students need to be supported through a writing project—graphic organizers, drafting pages, anchor charts, revision tools, and editing checklists—into one well-organized system.

This approach scaffolds the writing process from brainstorming to publishing, ensures that all resources are in one place, meets diverse learning needs, and empowers young writers to produce completed work they’re proud to share.

In this article, I’ll guide you through my process: how to plan the contents of your booklet, differentiate for your students’ varied needs, and print and distribute them to your students. To illustrate, I’ll reference the Realistic Fiction Writing unit I’ve taught to first- and second-grade students using this method.

Start with backward planning

Identify the key skills and standards you want students to learn by the end of the unit. For example, in my Realistic Fiction unit, I focus on teaching the structure of narrative fiction, considering how a character might change by learning a life lesson, and writing narratives with transition words. Knowing these objectives helps me choose the right graphic organizers, anchor charts, and writing supports for my booklet.

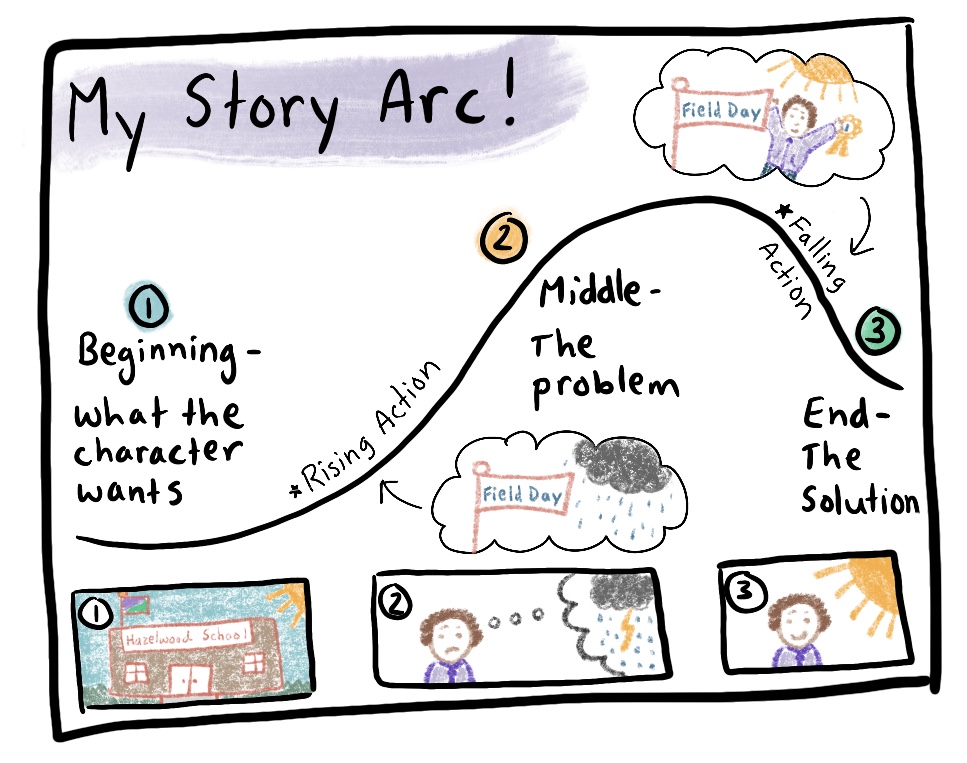

After I teach a lesson on planning story structure with a story arc, my students use the booklet’s planning pages to outline their own narratives. Writers are supported as they plan the Beginning (Who is your main character and what do they want? What is the setting?), Middle—Problem (Why can’t your character get what they want?), and Ending—Solution (How does your character get what they want?) by drawing and writing on a story arc graphic organizer. This alignment between lessons and booklet content ensures that students have the tools they need at every stage of the process.

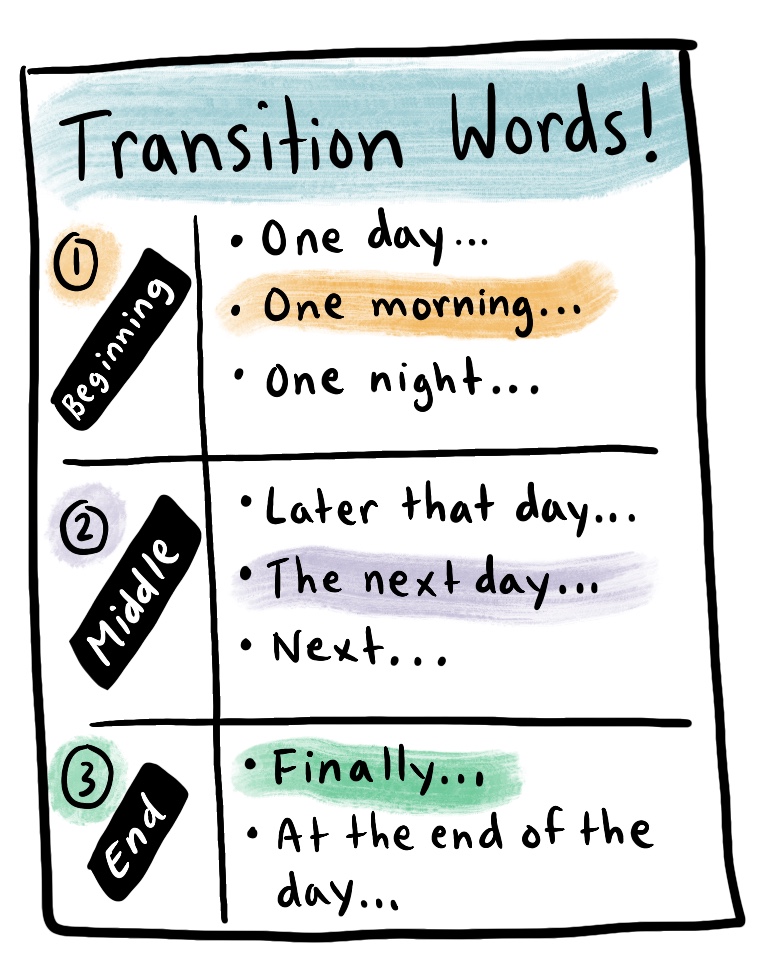

Later, when students are done planning and about to write their drafts, I use the same process. I teach a lesson on how to write a narrative with transition words and alert students to the transition word anchor chart included in their booklet’s drafting pages. On the drafting page marked “Beginning,” writers can choose from a list of transition words and phrases, such as “One day,” “One morning,” “First,” “To begin,” “It all started with,” etc. Each child can select the transition word or phrase they like, circle it, then copy it onto their drafting page.

Gather resources

Collect materials that align with your unit objectives, such as graphic organizers, anchor charts, writing paper, and editing checklists. Use resources from your school’s curriculum or other trusted sources, and if existing tools don’t fully meet your students’ needs, you can customize them.

For example, I wanted to teach my students how to include a change in their main character throughout the narrative as they learn a life lesson. I created a graphic organizer for young writers to plan a “life lesson” the main character will learn as their story unfolds and a list of common realistic fiction life lessons they might choose from—always tell the truth, be happy with what you have, friends and family are important, never give up, etc.

Differentiate for diverse learners

Tailor booklets to accommodate the varied needs in your classroom. One of the greatest benefits of DIY booklets is the ability to customize the content or structure of the booklets to meet the individual needs, abilities, and learning styles of each writer, while ensuring that all students work toward the same overall goals of the unit. Here are some examples.

- Advanced learners might receive a more complex story arc (planning the rising/falling action, additional conflicts, secondary characters, etc.).

- Students with dysgraphia might benefit from additional spelling and handwriting supports in their booklets.

- Emerging writers may need larger picture boxes for prewriting activities.

Differentiating booklets is especially helpful when working with split-grade classes to ensure that all students are appropriately challenged and supported. The booklets all have the same cover, though some pages inside may vary to meet individual needs. This helps every student to feel included.

Assemble and publish the booklets

Compile your resources into a structured booklet. A typical booklet includes the following:

- A cover/title page

- Planning and brainstorming pages

- Drafting pages

- Revision tools (e.g., anchor charts, checklists)

- Editing checklists

- An optional rubric at the end

To construct the booklet, print double-sided pages and staple them along the long edge so they open like a book.

Students store their booklets in folders or writing bins. For younger students, you may want to collect and store the booklets yourself between lessons.

The big reveal

Build excitement and engagement around your unit by introducing the booklets with flair. I like to present the booklets with ceremony to boost engagement. Students are eager to dive in, and many treat their booklet as their completed work. For prewriters or younger students, the booklet often becomes their final “published book,” which they proudly share. More adept writers may rewrite drafts on fresh paper, but the choice is theirs.

Sharing these booklets with families is also a wonderful way to highlight the process behind their child’s completed work. DIY booklets simplify and enhance the writing process, helping young learners stay organized and engaged while building their confidence as writers.