A Strategy for Differentiating Assessments

Tiered assessments help ensure that all students can show what they know while being appropriately challenged.

Your content has been saved!

Go to My Saved Content.Tiered assessments allow teachers to deliver individualized instruction through both summative and formative assessments. Pushing back against the idea that every student should take the same test, a tiered assessment allows teachers to create leveled assessments and to either assign students to a tier or allow students to choose their own tier.

Why Introduce Tiered Assessments?

Few, if any, teachers would argue against the practice of making learning accessible to every student. Additionally, there’s not an educator I know who would tell you that a student’s score on a standardized test delivered on one afternoon tells a better story than they can after teaching the student for an entire year. The term standardized test not only elicits cringes from teachers but also exists in direct opposition to the beliefs inherent in differentiated instruction. And yet, we still make every student take the same unit test and complete capstone projects with the same requirements.

Instead, what if we utilized tiered summative assessments? Tiered assessments create pathways that are accessible, and challenging, for all students. Physical education teachers have to do this every day. They differentiate their bench press assessment with data to back it up. Not everyone in sixth-period Weights class can bench-press 225 pounds. The teacher certainly didn’t begin the semester with the goal that everyone would bench-press 225 pounds. Instead, they began the semester with the goal that everyone would set a personal record, they would do it safely, and they would be able to explain the muscle groups necessary in doing so.

How to Utilize Tiered Assessment

The idea of tiering assessments is certainly not new. It takes its roots with Carol Ann Tomlinson et al.’s The Parallel Curriculum and Joseph Renzulli, Thomas Hays, and Jann Leppien’s The Multiple Menu Model. However, those come at a more macro scale—a curricular shift. A tiered assessment is a smaller instructional shift. It’s a move that can be implemented immediately, regardless of the curriculum, regardless of grade level. It takes three simple steps: data collection, creation, and delivery.

Data collection is far and away the easiest component. Teachers have a wealth of data, and they can use it to guide how many tiers they need for their next assessment, as well as which students need which tiers. If a math teacher provides two formative assessments throughout a unit on turning mixed numbers into improper fractions and 50 percent of the students haven’t mastered the process yet, she knows she needs two tiers for her next assessment. Half of her students are ready for a challenge, and half of her students are in need of remediation. To assign the entire class the same summative assessment would be the wrong move for 100 percent of the students.

Teachers at our school have begun to build and deliver tiered assessments in three main ways: tiering by complexity of product, tiering by complexity of content, and tiering by choice.

Assessments that are tiered by the complexity of the product are often referred to in our building as “Walking, Running, Sprinting” assessments (though they don’t need to be presented to students as such). To tier an assessment this way is to create three tasks that assess the same skill, but the products that students create increase in complexity. This AP Language and Composition assessment is an example of this with the blue, green, and orange tasks acting as the walking, running, and sprinting tasks, respectively. Teachers can assign individuals or groups to particular tasks based on data collected prior to the assessment. In this example, I determined which task students were assigned based on a previous Socratic seminar, an argumentative essay, and a multiple-choice formative assessment.

Assessments that are tiered by complexity of the content are often delivered in multiple forms. Perhaps a teacher creates Forms A, B, and C for an end-of-unit assessment in an eighth-grade Physical Science class; all three forms assess multiple skills, but the content on Form C is far more complex than the content on Form A. Or, in a project-based learning–organized Robotics course, a performance task that requires students to build a rescue robot could range from just a few weight constraints all the way to multiple constraints on the robot’s weight, materials, and frequencies.

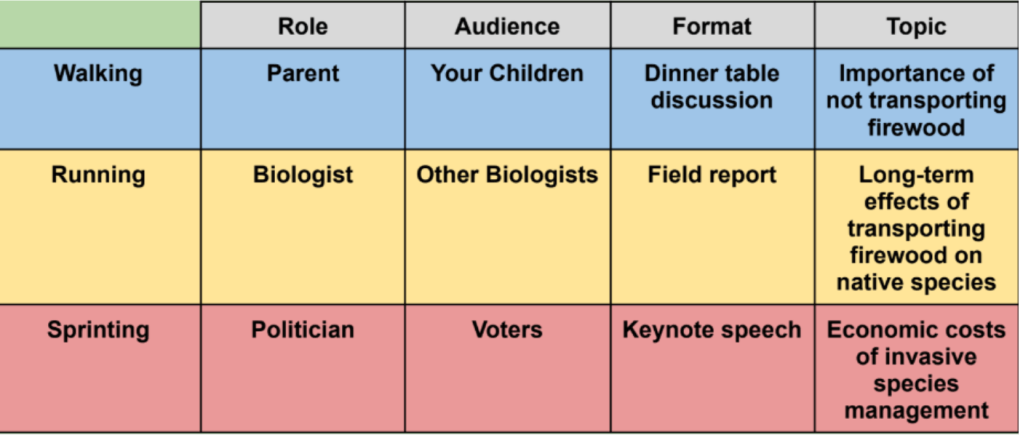

Finally, in our building, tiering an assessment and allowing students to choose their tier is often approached through a Role, Audience, Format, Topic (RAFT) approach. In both of these methods, the tiers are made explicitly clear to students, and they are given the space to choose for themselves which avenue they’d like to take. Typically, allowing students to choose their tier is reserved for larger group projects. Below is a RAFT that can be used in the Physical Science class mentioned above.

Similarly, tic-tac-toe boards, choice boards, and learning menus are all in this same category. They allow teachers to prompt students with multiple performance tasks while still allowing the space for autonomy.

Considerations for Tiered Assessments

Finally, a few disclaimers. First, my argument here is that tiered assessments are valuable and student centered. My argument is not that every assessment must be tiered or that students should be mandated to only complete tasks in one tier until the end of time. Instead, I’m encouraging teachers to embrace tiered assessments as another instructional move for their toolbox.

Furthermore, it is important to note that we are asking our teachers to increase the complexity of their tiers, not to increase the workload for students. As students progress and excel, they should not be punished with more work. Notice how, in all of the examples described here, the highest tier is never a task that requires students to teach their peers.

Finally, for the administrators, when the question of grading arises—and it will—it’s important to remember that we are chasing competency and mastery, not competition. Any student attempting any tier can absolutely earn an A. This, of course, is part of a much larger conversation about proficiency-based instruction and the arbitrary nature of grades in general; however, the refrain for this mindset is quite powerful: Even in the real world, mastery-level professionals have to carry out tasks at a range of difficulty levels.