When Middle School Students Think Like Historians

Students can learn about implicit bias by investigating the cultural assumptions underlying their history textbooks.

Your content has been saved!

Go to My Saved Content.Cultural assumptions about gender and race affect the construction of historical narratives and, as a consequence, the selection of instructional resources and the development of school curricula. Women, racial minorities, and LGBTQ individuals, for example, are generally either excluded from historical narratives or presented as marginalized and passive witnesses to history.

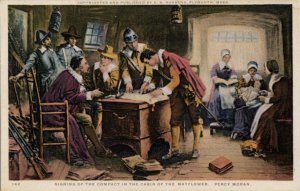

This was brought home to me during a Socratic seminar deconstructing accounts of the early English settlements in North America. One of my middle school students connected two images from our text. First she noted that Edward Percy Moran’s Signing the Mayflower Compact (1900) portrayed women as passive observers to the historic moment. Next, looking at an image of the wedding ceremony of Pocahontas and the Englishman John Rolfe, she commented, “Isn’t it weird that women are just sitting by watching things happen? They only seem to be important because they get married or have kids.”

This was a profound observation about agency, voice, and identity in history class that resonated with many of the student’s peers, and a small group of them remained after the bell rang to begin designing a research project on the significance of implicit bias and the historical record.

Acknowledging and Challenging Implicit Bias

The student researchers decided that we needed to raise and address our implicit biases about gender. They replicated an experiment detailed in Sam Wineburg’s Historical Thinking and Other Unnatural Acts that explored how students conceptualize abstract historic figures. Wineburg asked students to draw a Pilgrim, a Western Settler, and a Hippie. His team then tabulated the gender of the figures represented in the student drawings. He concluded, “If there is any point to our work, it is this: In girls’ minds, women in history are blurry figures; in boys’ minds, they are virtually invisible.”

My students were determined to replicate the experiment in class. Following Wineburg’s process, they sorted the pictures drawn by boys and by girls. Of the 38 pictures drawn by girls, 22 (58 percent) depicted male figures and 16 (42 percent) depicted female. Of the 39 images drawn by boys, 38 (97 percent) depicted male figures and one (3 percent) depicted a female figure. The data confirmed Wineburg’s research. Implicit bias about gender was affecting our students’ conceptualization and understanding of history.

Deliberately surfacing and acknowledging implicit bias provides an opportunity for a classroom community to challenge and ultimately redress that bias and move toward a more inclusive and accurate analysis of the past. The Institute for Humane Education has compiled a number of useful instructional resources that teachers can use to challenge students’ thinking and initiate a classroom dialogue about implicit bias and historical perspective.

Deconstructing Historical Narratives to Identify Implicit Bias

My students next engaged in a lively and at times heated conversation to explain the results of their experiment. They sought to understand how society constructed and perpetuated the biases they had identified.

To this end, the research team members organized their peers into groups to investigate how their textbook included, excluded, or portrayed women. These groups identified and characterized every image in their history textbook. Of the 519 images that included people, the overwhelming majority depicted men: 290 (57 percent) contained only male figures, 54 (10 percent) contained only female figures, and 129 (25 percent) included men and women. (In roughly 8 percent of the images, figures were obscured or in the distant background and my students were therefore unable to determine the gender of the figures.)

While this numerical disproportionality was striking, students also used a visual literacy protocol to analyze the composition and subject matter of the images. Ultimately, they determined that women were generally depicted in one of four ways: as passive observers of history, active consumers and leaders in the domestic sphere, supporters of male agency and activities, or leaders in the suffrage and civil rights movements.

Our analysis was not scientific or comprehensive, but the experience led to important conversations about the construction of historical narratives, gender bias, agency, and historical significance. We concluded that our instructional resources were an important mechanism in the process of constructing and perpetuating implicit bias and stereotypes.

Teachers can interrupt the construction of bias by designing instructional experiences that require students to deconstruct historical narratives and ask questions about power, agency, and representation. Teachers with classroom libraries or customized history readers with primary sources should consider having students conduct a diversity audit. The Geena Davis Institute on Gender in Media also has a number of useful lessons to help students apply these skills to digital media. If students habitually and repeatedly interrogate primary and secondary sources, they will develop the habits of mind required to identify and confront biased narratives.

Guiding Students to Think Like Historians

Teachers can provide a more inclusive experience by helping students to read and think like historians and develop the capacity to identify the underlying gender, race, or sexual orientation assumptions found within historical narratives. As part of this work, teachers can deliberately select materials that offer a wide variety of interpretations and perspectives and habitually allow students to select topics and content for further research and exploration.

This is particularly useful when students are explicitly challenged to consider perspective and surface historically marginalized voices when selecting research topics. Empowering students will remove a filter imposed by well-intended teachers and curriculum designers, provide additional access to a variety of historical perspectives that may have been missed or ignored in the curriculum writing process, and ultimately, develop agency and autonomy in the history classroom.