When Your School Is a Museum

In Grand Rapids, Michigan, an award-winning school has been the catalyst for a district turnaround after a 20-year decline.

Your content has been saved!

Go to My Saved Content.Sometimes, between classes, Zenobia Banks descends a flight of stairs to a small room where juvenile, several-inch-long lake sturgeon swim in an oversized tank. Upstairs in the classroom where Banks, 13, attends seventh grade, a window looks onto the Grand River, whose rushing waters are home to adult sturgeon more than 7 feet long.

A student at a novel middle school located inside the Grand Rapids Public Museum, Banks is eager to tell you about the historic importance of the sturgeon in the diet of the region’s indigenous Anishinabek, as well as the details of its overfishing by white settlers and its present-day endangered status.

Banks can also relate much of what she’s studying in her fourth-floor classroom with the museum’s varied exhibits and local landmarks beyond the galleries. Comparing this school to her old one, where the subjects changed throughout the day but kids stayed in their seats, Banks says she loves learning out in the city.

“This school is more active—there’s more to do here because we have all of Grand Rapids,” she says, reflecting on her class’s regular visits to downtown spots like the river, City Hall, and the library. “Just knowing we’re going to have hands-on work and do projects is exciting to me.”

Launched in the fall of 2015, the Grand Rapids Public Museum School currently has 120 students in sixth and seventh grades, and will add a grade each year so it’s fully enrolled as a 6–12 program by 2022. At the school, educators regularly incorporate the museum’s collections into curriculum, and student learning is grounded in real-world problem solving in the community.

The experiment in place-based education earned the 17,000-student Grand Rapids school district a coveted $10 million grant from XQ: The Super Schools Project in 2016, one of 10 awards made to schools and districts around the nation that challenge conventional ideas of what high school is.

The Museum School is also one of the district’s 15 “theme” and partnership schools—which include a school in a zoo and one in a nature center—created as part of a turnaround strategy after a 20-year decline that resulted in the closure of 35 schools, $100 million in budget cuts, and loss of 1,000 jobs, 600 of them teachers.

This school is more active—there’s more to do here because we have all of Grand Rapids.

Demand for these schools is bringing families back to Grand Rapids and has inspired the district to work hand in hand with an array of other partners that include colleges, businesses, farms, and even the Grand Rapids Symphony and the Gerald R. Ford Presidential Library to transform its schools.

The approach appears to be bringing a steady drumbeat of good news to the high-needs district, where nearly 80 percent of students qualify for free and reduced-priced lunch and more than three-quarters of students are people of color.

Last fall, Grand Rapids Public Schools’ enrollment grew by 160 students—the first increase in two decades—and six schools made it off the state’s list of lowest-performing schools. There was also a 16 percent increase in the graduation rate in 2016, adding to a nearly 50 percent increase over the last five years, with particularly pronounced improvements for black and Latino students. Recently, Grand Rapids residents endorsed the new direction, approving a $175 million school bond that will pay for long-overdue renovations—and more theme schools.

From a Point of Despair

When Teresa Weatherall Neal graduated from Creston High School in 1977, she went to work as a receptionist for the Grand Rapids superintendent by day and attended college at night. By the time the school board asked her to take over as interim superintendent in January 2012, she had worked her way up to assistant superintendent.

Those 35 years had taken a toll on the district. Between 1997 and 2015, enrollment dropped by 12,000 students. Over a third of Grand Rapids’ schools had fallen below 60 percent of capacity, including two brand-new ones, as more and more families decamped for local charter and private schools, or moved to other districts.

From Neal’s vantage point, the district needed to make significant changes to get back on a sound financial footing and bring families back to its schools.

“We had just come to a point of despair here. I told the board if I was the interim superintendent I would make drastic changes. I would close schools,” she recalls. “Everybody told me, ‘You’re gonna die on that hill and be done.’”

Neal spent the better part of her first year meeting with everyone she could on a listening tour, asking for feedback and ideas for how to make the district better. Parents and community groups called for technology and building improvements, more specialized schools, and an end to the constant upheaval.

After closing 10 more schools, including her alma mater, Neal turned back to the community to put their ideas into action.

Innovation blossomed in unexpected places, rooted in partnerships that helped launch place-based schools like the Museum School and the Center for Economicology. The successes inspired an outpouring of support across the district.

Even though this is a large city, it feels small in terms of reaching out for help. The community has always been there financially. The difference is they are there now with a voice and a sense of responsibility.

The Steelcase Foundation sent more than 100 district leaders to Harvard to acquire new skills in areas like cultural competence. A local brewery paid for education technology at an elementary school. Neighborhood associations now run elementary school open houses at people’s homes and businesses. And Habitat for Humanity is building affordable housing for local families near a new high school campus, which students from the district’s architecture theme school will help them build.

“Even though this is a large city, it feels small in terms of reaching out for help,” said Neal. “The community has always been there financially. The difference is they are there now with a voice and a sense of responsibility.”

Parallel Challenges

Neal’s most steadfast partner in the turnaround proved to be the city itself, which—like the school system—has struggled to keep existing residents and attract new ones. The converted lofts and brewpubs that pepper the city’s older residential areas have helped, but they aren’t enough, says Mayor Rosalynn Bliss.

“We want families to move here and to live here and stay here, and that’s pretty hard to do without a strong school system,” said Bliss, now in her second year as mayor. “We have deep racial disparities in our city. We have high rates of poverty in pockets of our city. We can’t be a great city if we don’t address that.”

The city’s community and cultural institutions were suffering as a result. Though the city was legally obligated to operate a public museum, it could no longer afford to do so, and a survey of city residents’ priorities ranked the existence of the museum, which opened in 1854, dead last.

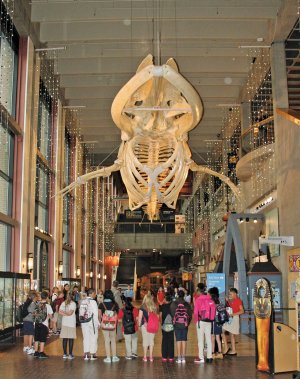

Museum president and CEO Dale Robertson was convinced that displaying items from the past in glass cases was, in many ways, an antiquated experience. He believed people, especially children, would have a more powerful connection to the museum if they were exposed directly to the artifacts, which fill a three-story warehouse nearly the size of a football field.

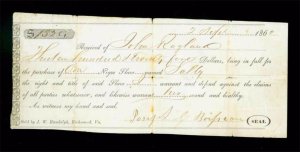

“We have in our collection a slave receipt—it has a girl’s name on it,” said Robertson of the museum’s archives, 90 percent of which were donated by local residents. “Holding that, in a protected fashion, that’s something. That’s a visceral experience.”

During a jog one week with the school board president, Robertson confessed that he’d dreamed of housing a school in the museum, an idea that helped school and local leaders reimagine their parallel challenges as an opportunity to share resources, space, and ideas.

With support from a host of community partners, the district spent more than a year preparing the museum and its teachers before opening two years ago.

Each year, the district pays the museum $35,000 per grade to help support the school, three-fourths of which funds museum education staff, who meet regularly with teachers and a curriculum integration specialist to brainstorm opportunities to tie lessons to collections and exhibits. Teachers also receive intensive training in design thinking and place-based education instruction, which includes attending a three-day workshop at the Henry Ford Learning Institute.

An Indelible Sense of Place

The museum’s rotating exhibits—which have ranged from King Tut to robots—regularly provide hands-on opportunities to deepen lessons that could otherwise prove abstract for students.

On a recent Tuesday, “Creatures of Light,” a new exhibit on bioluminescence, brought evolution and genetics to life for Banks and her seventh-grade classmates. Led by museum curators, students fanned out to investigate why living organisms might develop the ability to produce light.

One by one, Banks and her peers crammed into replicas of northern New Zealand’s Waitomo Caves in which artificial glow worms attached to a faux rock ceiling spun bioluminescent threads that, in real life, would catch bugs. As the kids explored a darkened room dedicated to fireflies, teachers and museum staff compared notes about the specific chain reaction that allows the glow worms to light up.

The collaboration between museum staff and teachers is still a work in progress as they continue to look for new ways to use museum and city resources to improve student learning, according to the Museum School’s principal, Christopher Hanks.

“We knew the school would be defined by its community engagement and partnerships,” said Hanks, a former professor of education from nearby Grand Valley University. “We don’t have a library—the public library is a mile away. We don’t have a gym—the ice-skating circle is down the street, and the YMCA is a couple of blocks away.”

It’s an approach that seems to be catching on throughout the city.

When the high school opens in two years, it will house an institute that shares the Museum School’s best practices with other teachers in Grand Rapids and other districts.

Museum administrators also plan to use the school’s model to bring in more visitors and let them touch and learn about their collections, and the city is about to launch one of the largest river-revitalization projects ever undertaken in the namesake Grand River. Museum School students and city residents will participate in the effort, right down to restoring the reefs where the sturgeon spawn.

When Banks becomes a member of the school’s first graduating class next year, the sturgeon that now keep her company during quiet moments in the school day will still be years from maturity. If all goes as planned, by coming to understand their unique relationship to the river and its wildlife, she’ll leave with an indelible connection to—and responsibility for—the place she calls home.