Demonstrating Authentic and Rigorous Learning in PBL

Ensure authentic, rigorous PBL learning by ensuring that students create relevant artifacts, by designing intentional self-assessment opportunities, and by having students present to authentic public audiences.

Your content has been saved!

Go to My Saved Content.Project-based learning (PBL) has the potential to ignite students' passion in civic purpose and social responsibility, but how do we ensure that projects also demonstrate rigorous learning? Addressing this challenge requires robust approaches for assessing how learning happens through projects. But this doesn't mean that we have to take the fun, authenticity, or social relevance out of projects! Rather, we need to make opportunities to demonstrate learning more explicitly in PBL settings.

A recent literature review of PBL (Condliffe, Visher, Bangser, Drohojowska, & Saco, 2015) (PDF) and the work of educational researchers and practitioners point to three approaches that have potential to enhance authenticity and rigor in PBL through assessment.

1. Create artifacts that really answer the driving question.

In PBL, the driving question serves more than just to provoke student interest. According to Krajcik and Czerniak (2013), a driving question should be:

- Feasible

- Worthwhile

- Contextualized in the real world

- Meaningful to learners

- Ethical

The driving question should motivate students to learn and apply rigorous content to solve a challenge that matters in their community. Krajcik and Shin (2014) are clear about the role of artifacts in this regard:

To ensure that student-generated artifacts will be effective, the connections between the driving question, artifacts, and core concepts and practices need to be explicit. When planning projects, consider an evidence-centered design perspective (Mislevy & Haertel, 2006) that takes into account the relationship among the learning goals, evidence, and features of artifacts:

- Which core concepts and practices are needed to answer the driving question?

- How will students demonstrate evidence of core concepts and practices (for example, standards) in their artifacts? What will students need to say/do/produce so that their learning is apparent to you and others?

- What artifacts will best answer the driving question (physical representations, writing samples, exhibits, analyses, etc.)? What are the advantages and limitations of different artifacts for enabling students to show what they know?

2. Design intentional opportunities to promote self-assessment, reflection, and revision.

Reflection and revision are at the heart of good formative assessment practice. As Linda Darling-Hammond and colleagues (2008) describe, we want students to "reflect deeply on the work they are doing and how it relates to larger concepts specified in the learning goal" (p.216). PBL, even more than other kinds of learning environments, has the potential for empowering students to develop this practice authentically because students work on artifacts over a number of weeks to answer a driving question. To promote and sustain reflection and revision in PBL requires intentionality:

- Provide planners and rubrics with student-friendly language and clear criteria (Berger, Rugen, & Woodfin, 2014). These kinds of tools help students monitor how well their artifacts answer the driving question and demonstrate their learning of core concepts and practices.

- Plan opportunities throughout a project when students' ideas can be tested to provoke reflection and revision, and to deepen understanding (Minstrell, Anderson, & Li, 2011). Consider what kinds of contexts or situations are needed to challenge current perspectives and surface new ideas.

- Orient feedback toward students' reasoning and practices in the subject matter (Coffey, Hammer, Levin, & Grant, 2011). Press students to explain their reasoning and how they are applying ideas to respond to the driving question.

3. Present artifacts to authentic public audiences.

Demonstrating learning and "college and career readiness" is not just about meeting standards. We can't underestimate the sense of accomplishment when students realize that what they are learning matters in their community and in the real world. Creating and presenting artifacts for public audiences are ways to simultaneously connect authenticity and rigor. To enhance project-based learning opportunities with public audiences:

- Engage experts outside of the classroom before the end of a project. For example, Polman and colleagues (2014) set out to engage youth participants in "authoring science news centered around a rigorous publication venue" (p.778). The journal editor provided feedback to students about the content (not just grammar and style) of their articles. Although only one revision was required, many students were motivated to do multiple revisions.

- Develop clear criteria with students for how to communicate effectively. In Polman and colleagues' project, the writing criteria for science news articles included "present the personal or local impact of a timely, narrow, focused topic of interest to the audience from a unique angle" and "communicate information that accurately represents up-to-date science and forefront the most important elements."

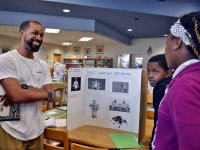

- Bring the school community together to celebrate and share what has been learned in projects (Lenz, Wells, & Kingston, 2015). In some cases, the school community may be the target audience. At other times, sharing with the school community can serve as an opportunity to model for fellow students and parents how to participate in meaningful learning through projects.

The three strategies detailed in this post can help you in addressing those PBL skeptics who question the rigor in PBL and who think that simultaneously addressing rigor and authenticity is too grand of a challenge. In reality, rigor and authenticity go hand in hand. Let's show how it is possible! In the comments section below, please share your PBL assessment strategies.

Notes

- Berger, R., Rugen, L, & Woodfin, L. (2014). Leaders of their own learning: Transforming schools through student-engaged assessment. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass.

- Coffey, J. E., Hammer, D., Levin, D. M., & Grant, T. (2011). "The missing disciplinary substance of formative assessment." Journal of Research in Science Teaching, 48 (10), 1109-1136. doi:10.1002/tea.20440.

- Condliffe, B., Visher, M. G., Bangser, M. R., Drohojowska, S., & Saco, L. (2015). Project-based learning: A Literature review.

- Darling-Hammond, L., & Barron, B., Pearson, P. D., Schoenfeld, A. H., Stage, E. K., Zimmerman, T. D., Cervetti, G. N., & Tilson, J. L. (2008). Powerful learning: What we know about teaching for understanding. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass.

- Krajcik, J.S., & Czerniak, C., (2013). Teaching Science in Elementary and Middle School Classrooms: A Project-Based Approach, Fourth Edition. Routledge: London.

- Krajcik, J. S., & Shin, N. (2014). Project-based learning. In R. K. Sawyer (Ed.), The Cambridge handbook of the learning sciences (2nd ed.) (pp.275-297). New York, NY: Cambridge University Press.

- Lenz, B., Wells, J. & Kingston, S. (2015). Transforming schools: Using project-based learning, performance assessment, and common core standards. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass.

- Minstrell, J., Anderson, R., & Li, M. (2011). Building on learner thinking: A framework for assessment in instruction. Commissioned paper for the Committee on Highly Successful STEM Schools or Programs for K-12 STEM Education.

- Mislevy, R. J., & Haertel, G. D. (2006). "Implications of evidence-centered design for educational testing." Educational Measurement: Issues and Practice, 25 (4), 6-20.

- Polman, J. L., Newman, A., Saul, E. W., & Farrar, C. (2014). "Adapting practices of science journalism to foster science literacy." Science Education, 98 (5), 766-791. doi:10.1002/sce.21114.