Letting Students Succeed as Themselves

An American teacher shares a lesson learned during time he spent in New Zealand schools.

Your content has been saved!

Go to My Saved Content.For many students, the experience of school is a series of lessons on the necessity of submerging their primary identity and culture in order to succeed academically. These students are repeatedly taught about “appropriate” behavior and that the path through school, and many parts of life, is easier if one conforms to “mainstream” cultural standards.

Students need tools to navigate a range of spaces throughout their lives, and demanding that they conform to one standard silences them and sets the stage for endless struggles over compliance. Whether this happens by design or by default, the result is that many students experience school learning as something external to who they are and what matters to them. In contrast, creating meaningful learning experiences for students allows both students and teachers to experience school as a place of engagement, deeper meaning, and discovery.

Getting a New Perspective

During four months this spring I had the honor of working with teachers in several schools in Aotearoa New Zealand. I use both the indigenous and the colonial names, as do many others, to emphasize the bicultural aspect of the society. In Aotearoa New Zealand, there is official, legal acknowledgement that there is more than one dominant culture and that there are competing value systems, an acknowledgement that also exists in some schools.

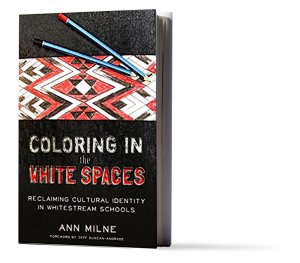

In her book Coloring in the White Spaces: Reclaiming Cultural Identity in Whitestream Schools, Ann Milne, former principal of a secondary school called Kia Aroha College, documents different ways Māori and Pasifika students have been able to succeed as themselves. This thinking is outlined in The Māori Education Strategy, or Ka Hikitia, published by the Ministry of Education. This document responds to a history of colonialism and unequal education outcomes by pushing for opportunity for Māori students to succeed as Māori.

This simple idea of allowing students to be true to themselves and their identities while investing in school is truly profound. In Ka Hikitia, this is described as helping “all Māori students gain the skills, qualifications, and knowledge they need to succeed and to be proud in knowing who they are as Māori.”

What if this idea were applied to other contexts? What if we in the U.S. worked to provide all of our students with knowledge to succeed and be proud in knowing who they are? School would be a different experience for these young people if they felt a connection to learning. School would be less about fulfilling external requirements and more about investing in a process that would be central to one’s current and future identity.

Fostering Student-Centered Learning

There are many teaching strategies that can help teachers undertake this shift toward truly student-centered education.

Prioritize Student Voices: When teachers move from the front of the room and encourage students to be the primary thinkers in the classroom, the dynamics of learning change and center on the responses and ideas of the students. This is not to say that teachers should disappear: They must facilitate, consult, and do the intellectual work of designing inquiry-based units and framing learning in order for the model to succeed. See more related strategies in one of my previous posts.

Emphasize Relationships Rather Than Compliance: When students know that they are valued as people and that their teachers care about their well-being and not just their grade, the dynamics of the classroom shift. There are many ways to check in with students and snatch time for short conversations that transform stereotypically adversarial student-teacher relationships.

Assume a Stance of Inquiry: Students know when teachers are poised to learn from them compared to times when they are working with someone who does not see education as a true exchange of ideas. When we reframe teacher voice and truly learn from students, teaching and learning become rich experiences that continually challenge both teachers and students to examine their beliefs and assumptions. Students are drawn to this central position in the learning process. Inquiry for teachers and students requires units built around big ideas and essential questions that are designed for collective examination. Chris Emdin’s ideas about reality pedagogy challenge teachers to use dialogue and co-teaching (among other strategies) to share and create knowledge with students.

Kiwa, a student profiled in Coloring in the White Spaces, asks, “What good is an education that completely diminishes your cultural right to know who you are, what you are, where you’re from, and what blood runs through your veins?” She’s right. The question helps us remember that school can be a place where students from all backgrounds discover the depth, possibility, and wisdom within their voices. School can be where students begin to understand the many layers of who they are and their different roles in society.

We’ll all be better served if we permanently move past ideas of school as a uniform experience meant to transfer information. Learning has real meaning and teaching truly matters only when they are parts of a process of affirmation and transformation.