Penn-Finn Learnings 2013: How We Value Our Teachers

Your content has been saved!

Go to My Saved Content.Much has been made in the media and press about the Finnish education system. Our goal this week is to uncover the beliefs and practices that contribute to a successful education system here. To help us delve into this topic, we spent time visiting the University of Helsinki, a leading teacher education institution in Finland. Dr. Jari Lavonen shared the history of the Finnish education system and several key characteristics of their approach. Lavonen called our attention to these four characteristics:

1. Common, Consistent and Long-Term Policy

The models for teacher preparation and comprehensive education are 40 years old and do not change drastically from year to year. Unlike in the United States, Finland's education policy is not tied directly to political parties or the "reform of the day." Sustained, strategic policy and practice are the norm.

2. Educational Equality

The Finnish system attempts to mitigate socioeconomic backgrounds, education is free, and well-organized special education and counseling are available to any student who needs them.

3. Devolution of Decision Power to the Local Level

Leadership and management reside at the school level, with decisions about curriculum and assessment residing with the faculty.

4. A Culture of Trust and Cooperation

In the Finnish system, trust and cooperation are based on professionalism. Teachers are viewed as professionals with academic expertise. There are no inspectors making sure that teachers are doing what they should, and there are no widespread national exams.

The Notion of Experts

It's been hard to reflect on these characteristics and not compare how they would play out in the United States. One could argue that education policy in the U.S. has become highly politicized and far from consistent over the last 40 years. Having a consistent, sustained focus has allowed schools in Finland to adjust to meet the needs of students and local expectations, while not spending inordinate amounts of time responding to top-down mandates and regulations.

Teachers in Finland attend one of eight higher education institutions that focus on teacher preparation. Having a smaller population allows them greater oversight and consistency in their approach to preparing teachers. Much of the autonomy that is afforded to teachers is due to the rigorous education they must complete before entering the teaching ranks. But even before the teachers earn their degree, the admissions process is much tougher than you might find in the U.S. At the University of Helsinki, there were 1783 applicants for the primary teacher Master's of Education degree, but only 120 were accepted (a 6.7% acceptance rate). In essence, being selective about who enters the teaching force is a major cause for the trust that is extended to teachers and schools.

Dr. Lavonen was joined by his colleagues, Dr. Heidi Krzywacki and Dr. Atso Taipale, who both confirmed that part of the reason teachers are trusted and afforded respect is because of the level of education they attain. According to Dr. Krzywacki, "We believe in the notion of 'experts,' and trust individuals whether they be doctors, teachers or plumbers." As such, teachers are viewed as experts in youth development and learning. Based on this expertise, they are expected to engage in scholarly endeavors, such as consuming and producing research, and are provided tremendous autonomy to make decisions about curriculum, instruction and assessment in their classrooms.

Do We Really Trust Our Teachers?

I wonder if the United States can say it trusts its teachers the same way. The evidence would suggest not. In the U.S., there are many approaches and pathways for training individuals to become teachers, causing inconsistent expectations and outcomes in teacher education. It would seem that the ongoing discussions about "teacher effectiveness" and the creation of evaluation systems focused on measuring a teacher's capacity (increasingly based on test scores) often do very little to actually develop that capacity. A strong emphasis on teacher evaluation and measuring effectiveness has led to increasing skepticism about American teachers and a lack of trust. Compared to the Finnish approach, it would seem that teachers in the U.S. are viewed through a deficit model instead a model that focuses on their competence and expertise.

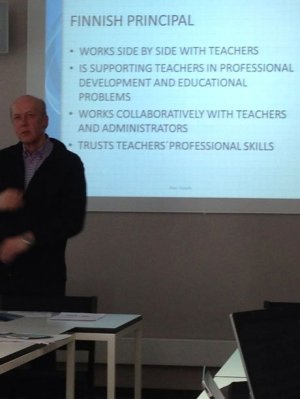

Dr. Taipale shared that, as a former principal for over 30 years, he was not expected to conduct formal teacher "evaluations" or observations. Instead, his role was to "work side by side his teachers, support teachers in professional development and solve educational problems." When I asked him what would happen with a teacher who struggles, he explained that teachers who struggle get assistance from peer teams and targeted training. He shared the belief that making mistakes was acceptable, but that support would be provided to build the teachers' capacity to ensure growth.

It strikes me that the conversation and tenor around teachers in the United States is not as forgiving or supportive at this time. Instead of respecting teachers as the well-prepared professionals that they are, many policies seem to be dismissive and reductive in nature. Perhaps this is just as much an indictment of the teacher preparation programs in the United States as it is of the teachers themselves. If our communities, education leadership and policy makers displayed more trust in our teachers, how would they respond? If we made the assumptions that teachers are highly trained professionals prepared to make the best decisions about their students' needs, would our culture of testing and teacher evaluation look different? Lastly, if greater autonomy and decision-making were reserved for the local level, would schools be more responsive to student needs and provide more personalized learning experiences?

If nothing else, the United States could certainly take a page out of the Finnish "play book," and make the effort to raise the prestige and standards for teaching excellence the centerpiece of U.S. education policy and reform.