Teaching Children About the Brutality of War

Your content has been saved!

Go to My Saved Content."Why?" he asks, over and over, as I attempt to narrate a series of historical events. I'm not prepared for these questions and I'm surprised, and a little disappointed in myself, that I was caught off guard.

But who has adequate answers to the "Why?" questions when you're trying to teach children about the horrors that have been perpetrated on innocent humans? Who is able to sufficiently explain war?

Laos

I'm in northern Laos with my husband and nine-year-old son. We're in the small city of Luang Prabang, the UNESCO-preserved, ancient royal capital, a city surrounded by mountains and nestled between two rivers and said to house 30 Buddhist temples and over 1000 monks. We wake up at dawn every day to watch the alms procession: hundreds of monks silently make their rounds through the city, clad in saffron robes, receiving food from the locals. Boys younger than my son are amongst these monks, many of whom join the temples as a way to get a free education.

Laos is the poorest country in Southeast Asia, with the average annual income about $1000. When I share that statistic with my son, he responds with a barrage of "Why?" questions. How do you explain poverty to a nine-year-old? And yet, this is what I want him to ask.

"It's the history," I start with. "You can't understand why people are so poor without understanding the history." I'd become a history teacher because of how strongly I believe in this -- can't understand the present without understanding the complicated, messy past.

And so I begin with colonialism and attempt to explain how it was that a few European powers came to dominate most of Africa, Latin America and Asia. I'm doing okay with the "Why?" questions at this point even though this series of events is still hard for me to digest.

Shocking Facts

It all falls apart when we get to the U.S. government's secret bombing of Laos. Here are the facts, in case you don't know them:

- From 1964 to 1973, the U.S. dropped more than two million tons of bombs on Laos, equal to a planeload of bombs every eight minutes, 24 hours a day, for nine years.

- Laos is the most heavily bombed country per capita in history.

- During those years, countless villages were destroyed as well as fields and livestock, and hundreds of thousands of Lao people were displaced. The number of dead was difficult to determine.

- The war and destruction and suffering didn't end after 1973. One-third of the bombs did not explode, and so, for over 35 years, the Lao people continue to be maimed and killed from unexploded ordnance.

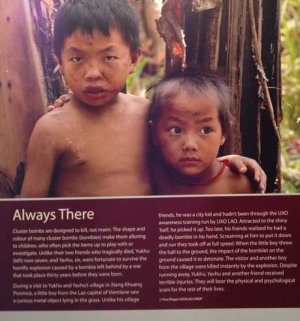

I want my son to know this history, so we visit the Unexploded Ordnance Centre in Luang Prabang. Here he sees dozens of these devices that had caused so much destruction, as well as photos of maimed children.

I try explaining about the Cold War and how the U.S. government felt that if Vietnam "fell" to the communists, all of Southeast Asia would crumble, and then the entire developing world, and then the Soviets would take over the U.S. I try to explain about the Ho Chi Minh Trail and the North Vietnamese Army and so on.

My son gives me blank looks. This explanation sounds hollow and absurd as we stand in front of images of children maimed by U.S. bombs. We're also struck by the contrast of this brutality from the most powerful nation on earth upon a country of Buddhist monks, peasants and weavers. The Laotians we meet every day are kind, quiet, gentle and gracious. At breakfast on our first morning, the young man serving us in the small hotel where we're staying says, "Please if you would like anything else, please ask. We are very kind people." I can't imagine how indiscriminate bombing could have ever made sense, and even though I have a deep understanding of the history and geopolitical landscape of the 1960s, it still seems absurd.

Why is Laos the poorest country in Southeast Asia? We watch a movie about the bombing -- it is graphic and disturbing, and I cry. And the movie explains how fields were destroyed during the nine years of war, and how for the last 35 years the Laotians have struggled to plant and grow food, fearing the detonation of unexploded ordnance that fell on their land decades ago.

My son keeps asking questions for days, "Why?" questions that I can't answer sufficiently. But these are the unanswerable questions, aren't they? A series of historical and political events can't explain human cruelty, which is what this feels like, here in northern Laos.

Back to the Classroom

I am never able to turn off my teacher-brain, so during this visit to Laos, I keep thinking about how teachers teach history to other people's children. I realize how, as a history teacher, my instruction was deeply infused with my own morals and values -- that killing is wrong, that the dominance of one political power over others is unfair. I realize how strongly I feel about being the one who provides these lessons to my child -- I want to be the one to supply a moral context for the history of the Cold War and the Vietnam War. And I question my own role as a history teacher -- what right do I have to provide the moral context for the history I teach to my students? How do we navigate this terrain in our public schools where we don't have shared moral and ethical codes?

Perhaps we provide a balanced perspective and try to explain the Cold War from the perspective of Henry Kissinger or the American politician who said he wanted to "bomb Laos back to the Stone Age." But no, I can't do that, unless I can also communicate the experience of the hundreds of thousands of Laotians who were affected by the war. Questions of power arise, and who has access to communicating their beliefs and experiences.

It feels complicated and impossible to answer the "Why?" questions. It also seems so clear and simple: dropping millions of tons of bombs on people is wrong. The ethical questions that arise are ones that societies have been trying to answer for millennia. We'll have to join the ranks of our many ancestors in finding ways to understand human cruelty.